Every Monday for the past eight years, Richard Beck has driven to the maximum-security French Robertson Unit in Abilene, Texas, where he volunteers as a chaplain, leading a Bible-study class for 50 inmates.

A few years ago, Beck, the author of Reviving Old Scratch and Stranger God, bought a copy of Johnny Cash's album At Folsom Prison. He had only a passing cultural knowledge of the Dyess native and knew the album was a recording of a live concert Cash had given at the California prison in 1968. Beck, who's also a psychology professor at Abilene Christian College -- approximately a 15-minute drive from the prison -- thought At Folsom Prison might make for a good listen on those Monday drives before leading Bible study.

The reaction of the inmates -- shouting, cheering, booing the warden -- captivated Beck. He went on to pick up a copy of At San Quentin and other albums, read biographies on Cash and deepened his knowledge about the country-music icon who began his career with hopes of becoming a Gospel singer.

"Cash's music dwelled upon darker themes ... the darker aspects of life, and his trying to give voice to the poor and the oppressed and the marginalized," Beck said. "That physical relocation of himself inside a prison, it's that move that speaks to me most powerfully of Jesus. To stand where somebody has been marginalized, that to me is putting your money where your mouth is, and that's what I liked about Cash's music. It's not when he's overtly saying 'Jesus,' but when he is standing as Jesus did with the broken and the lost."

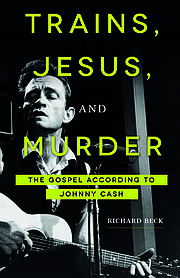

Beck examines a dozen of Cash's songs, and the musician's life and faith, in Trains, Jesus and Murder: The Gospel According to Johnny Cash. The book, released in November, was so named after Beck's son, Aidan, who remarked that "Johnny Cash sings about three things: trains, Jesus and murder."

"That contrast between Jesus and murder, between gospel hymns and odes to a criminal mentality -- and there is nothing like this contrast in the whole of the music industry -- is what fascinated me about the music of Johnny Cash," Beck writes.

The psychology professor described his faith as being at "a low ebb" at the time he began visiting the French Robertson Unit. Beck kept a passage in mind from Matthew 25, which in part refers to visiting the imprisoned.

It was similar, he said, to Cash's experience in seeking to perform in front of inmates at the California prison. After hitting rock bottom with drug addiction in 1967, divorced from his first wife, Vivian Liberto, and before he married fellow singer June Carter, Cash had been in a dark place.

"[Cash] went out to Folsom Prison in 1968 ... and recorded that live concert looking for grace, looking for redemption, a revitalization of his career and his personal life," Beck said. "And that's the connection I play with in the book -- about how my own story of finding grace and what would seem to be a dark world or place had a parallel to Cash's own journey with his prison concerts and albums."

Cash's early life in Arkansas had a profound effect on the country singer's music, Beck said. His journey as a musician began in singing gospel, a promise to his dead brother, Jack, who was killed at 15 in an accident involving an electric saw.

The unwarranted guilt Cash felt over Jack's death that "added some shadows to his personality and his psychology and his music -- and made him such a distinctive artist -- that happened in Arkansas," Beck said. "His experience growing up in cotton fields in depression-era Arkansas ... the things that make him so iconic as "The Man in Black," the black being the darkness but also standing with the oppressed, that began in Arkansas."

"In many ways, his entire career was a love song to Dyess, a love song to Arkansas."

Standing with the oppressed also shaped such music of Cash's as the song named for his moniker, "The Man in Black."

I wear black for the poor and the beaten down

Livin' in the hopeless, hungry side of town.

Cash's music is a sacrament of God's grace, Beck said.

"Sacraments are signs of invisible realities, and so what we do for each other ... kind of functions as sacraments of grace for each other," Beck said. "We stand in front of our children and try to breathe life into them, or we go to coffee with a friend and just listen to them pour out what's going on that week, or I go out to the prison just go give a guy a hug. He's never going to get a hug from anybody else outside the world."

Beck calls the music Cash created a "gospel of solidarity," as manifests through the chapters of Trains, Jesus and Murder.

"The Ballad of Ira Hayes" from Cash's 1964 album Bitter Tears tells the story of the American Indian who, barely 10 years after instantly becoming famous as one of the men photographed in Joe Rosenthal's iconic Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, died alone and despondent. And unbeknownst to Sam Phillips of Sun Records in Memphis -- the studio where Cash recorded his first music -- the song "I Walk the Line" was Cash's first gospel hit. In a tune about "walking the line" -- remaining faithful to his first wife, Vivian, and to God -- Cash would stray from both as his fame and his substance abuse grew.

A chapter is also devoted to "Greystone Chapel," the hit credited to Folsom Prison inmate Glen Sherley, for whose parole Cash advocated after meeting the man the day he recorded the prison album. Sherley, who joined but was later kicked off Cash's tour group after threatening violence and later committed suicide, illustrated "the cost and the heartache" of solidarity, according to Beck.

The book also covers the faith that weaves its way through tracks such as "Ragged Old Flag" and "Delia's Gone," and expounds upon hits Cash sang later in life such as "The Man Comes Around" and "Hurt," which was originally sung by Nine Inch Nails. Cash starred in the music video for his version of "Hurt," which won Grammy and Country Music Association awards; the song itself won the association's 2003 Single of the Year.

Beck dedicated the book to his family, and to the men of the French Robertson Unit in Abilene. Beck was raised attending a Church of Christ, known for its hymns sung unaccompanied by instruments, which Beck writes are sung in four-part harmony. The hymnals the men sing from during their Bible study had until then sat unused.

"I went out to the prison with the expectation or hope that I would meet God at the prison as a minister among the incarcerated," Beck said. "And that proved to be the case. I've found the last eight years to be a really invigorating and holy time out there."

About halfway through Bible study, Beck said, he and the men will pick up their hymnals and sing together. Sometimes they will sing until the guard comes around to let them know that the group's time is up for that day. Beck writes in honor of the men, "I wish the world could hear us sing."

"Again, it's just a sacrament of grace, a visible sign [of] the reality that they are seen and that they aren't forgotten," Beck said of the men. "Somebody knows their stories, and in some ways [is] telling their stories.

"Any good that comes from the book, they feel a part of because I'm telling our shared stories."

Religion on 01/11/2020