In 1835, there were about 600 souls at the Territorial outpost of civilization called Little Rock on the mosquito-infested banks of the Arkansas River. They were a pretty rough crowd, consisting mostly of white males and a few slaves, white women and American Indians. Inhabitants typically carried a firearm, a big knife or both. The Territory was full of tough and sometimes dangerous frontiersmen who lived by their own codes and dispensed their own justice with whatever weapon they had handy.

Such was the sordid setting for the story of Morgan Williams, who murdered Isam Pelton on Jan. 3, 1835, and was hanged that May 16 — the first public hanging at Little Rock.

I came across this case in an obscure book at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies while I was researching one of Little Rock's historic cemeteries, Mount Holly on Broadway. Scanning book titles, I noticed The Romance of the City of Roses, A Tale of a Southern City, written in 1886 by one Robert Brown. Brown seems to have started a small subscription magazine of humor plus tales and stories by older settlers, and he described his motives clearly as "my attempt to make money."

Flipping the pages, I read about the hanging, noting that the gallows was erected on a small hill south of town. From the description, I knew that hill later became my favorite cemetery, Mount Holly. The 1821 plat map of Little Rock shows a street named Holly about 10 blocks south of the Arkansas River, just about where the current cemetery stands. The map shows the Town Branch, a seasonal creek, cutting across the platted street.

Brown wrote that Williams' hanging was well attended and the gallows stayed up for a considerable time. Perhaps there were other hangings, but this is speculation. Brown wrote his account 43 years after the cemetery was founded in 1843.

Mount Holly's sexton, Steve Adams, and Kay Tatum, the archivist for the cemetery association, and other people knowledgeable of Little Rock history all told me this hanging was news to them as well. I posted a request for information on a few Facebook pages dedicated to history. Though it is fraught with danger, scammers and people trying to sell you everything, you have to love the internet. Within 24 hours, Caren Martin McNeill, a former teacher who grew up in Little Rock, sent me news clippings about the hanging that she found on the web.

My search was on.

If so inclined, gentle reader, you might wish to pour yourself a small shot of good bourbon or a glass of wine and take a seat.

A KILLING

Morgan Williams is not listed in the Territorial Census of 1820 or that of 1830. It appears his father lived in Little Rock, and there were a number of other Williamses in Pulaski County who might or might not have been related. Isam Pelton (sometimes spelled Isom) also is not in the 1820 or 1830 Territorial Census but does show up on the tax rolls of 1829. There are other Peltons on the tax rolls in the 1830s, too.

From a court transcript published May 1, 1835, in the Arkansas Times and Advocate, a Little Rock newspaper owned then by Albert Pike, we know Williams lived at a boarding house belonging to one Jarrett McCarty and his wife.

Several newspaper items described Williams as a "cripple with a lower leg drawn up to his knee and forced to use a crutch much of the time." His physical limitation apparently did not slow him down when he broke out of jail and fled south, stealing several horses. But I am getting ahead of myself.

January 31, 1835, was a Saturday. That month the Arkansas Gazette, which was published weekly, mentioned bitter cold, snow on the ground and ice floating in the Arkansas River.

At trial, Williams testified that Pelton came to see him at the boarding house and denied having made unflattering remarks about Williams. Several witnesses thought the two men then made up and put their difficulties behind them. Both went outside, mounted horses and rode away together in the direction of Little Rock. The witnesses noted that both carried guns.

Later in the day, other witnesses at another place saw them drinking and "shooting for liquor." One witness said he overheard Williams tell a third party that if Pelton and a man named Sam Nixon did not leave him alone, he was going to "up" one of them.

Williams and Pelton returned to the McCarty house late in the afternoon. Williams dismounted and went in, handing his rifle and shot pouch to Mr. McCarty, who was on the porch.

Williams called Pelton to come inside and have some more liquor. Pelton did not dismount. Instead, he hollered for Williams to join him for a drink outside.

Williams came outside, took a swig and then told Pelton he hoped he and Nixon were on the "mud sill of hell." A mudsill is defined as the lowest portion of a building usually resting directly on the earth, and the term was on occasion applied to a person of the lowest social level.

Pelton, still atop his horse, replied, "I hope you hang on the center hook of the fires of hell and that the fire is as big as Blakely Mountain."

In a Territorial fireplace, the center hook held the main cookpot over the hottest part of the fire. Blakely Mountain is a big mountain northwest of Hot Springs.

Proprietor McCarty wore a knife in a scabbard around his waist. Williams grabbed that knife and told Pelton if he failed to clear off the property he would "cut his damn throat."

Pelton then accused Williams of trying to start a fight with him all day and protecting "known horse thieves."

This was about the worst thing you could say to another man.

Still mounted, Pelton told Williams he would leave as soon as he finished his liquor. Then he put a stopper in his jug, turned and started to ride off. But he wheeled his horse around and pointed his gun in the general direction of the porch. One witness said he was pointing directly at Williams.

Reportedly, he threatened Williams by promising to "blow him to hell" if he came any closer, but witnesses disagreed over whether Williams advanced toward Pelton or stayed put.

McCarty's wife, who was now on the porch, screamed, "You are going to be shot." It is not clear from the trial testimony whether she was yelling at Pelton or her husband. McCarty was in the yard trying to lead the drunken Pelton away from Morgan Williams.

Williams raised his long gun — which he had picked up off the porch — and pointed it directly at Pelton, saying, "Don't shoot."

At this point, both men had their long guns up.

The facts seem clear that Williams then fired, hitting Pelton in the shoulder. Williams fired twice. (It must have been a double-barrel muzzleloader, given the shot pouch mentioned earlier.) One witness said Pelton aimed at Williams only after the first shot.

BOOM

The bullet traveled into the upper part of Pelton's body, and he fell off his horse. McCarty ran to attend Pelton, who said, "He has killed me."

Williams grabbed Pelton's horse. McCarty told him not to leave, but Williams rode off, saying he was going for the doctor. And he returned with a doctor.

Pelton's rifle was examined. Though cocked, it had not been fired: The firing hole was blocked by a feather. Small feather quills were put into the firing holes of cocked muzzleloaders so they would not go off.

Williams was put in the county jail Feb. 1, the day after the shooting.

Pelton was mortally wounded. He lingered in pain until the following Monday, when he died.

Note to the reader: Have a sip of bourbon.

DELIVERANCE

Williams was cooling his heels in the Pulaski County jail on the night of March 31, two months after his arrest, when six well-armed men with their faces painted black arrived.

They threatened the jailer with death unless he handed over his key. According to the April 7, 1835, Gazette, they released the three prisoners: Williams; Fielding G. Secrest, jailed for stealing horses and slaves and accounted a villainous man in spite of his youth; and a slave named Hiram owned by Emzy Wilson. Hiram had been captured after running away from Wilson on Feb. 13 and was in jail for "safekeeping." He was described as very black, stout and "likely" — meaning he was healthy.

It was never determined who the armed men were or whom they wanted released (see accompanying story), but I think it's a safe bet it wasn't poor Hiram, who fled with the others. The sheriff posted ads offering a $150 reward in the Gazette and Times and Advocate.

Meanwhile, Williams lit out for Texas. His bent leg does not appear to have slowed him down one bit. During his brief spell of freedom in March and early April, he stole several horses. Eventually, he was captured in Texas near Dooley's Ferry on the Red River and returned to jail in Little Rock.

Williams was now six weeks from a date with the gallows on the future grounds of Mount Holly.

JUDGMENT

The trial began in Little Rock on April 23, 1835, after what was described as a difficult jury selection. We don't know whether this was due to general orneriness or drunkenness of the small population or widespread bias against the defendant. The prosecutor was a Mr. Cummins. For the defense were court-appointed attorneys — a man named Childress and the now-famous Pike, later to become a Confederate general and poet laureate of Freemasonry. Pike and Cummins were Masons and undoubtedly friends.

After a lengthy trial in which a number of witnesses seem to have seen completely different events, the jury took three hours to find Morgan Williams guilty of murder.

Judge Benjamin Johnson on April 28 not only pronounced a sentence of death but also took the verdict as an opportunity to lecture Williams about his guilt and the eternal damnation of his soul. With Shakespearean eloquence, he told Williams he had shed the blood of his fellow man and the "offended laws" had pronounced his doom.

He told the prisoner, "Though man has no power to forgive or pardon you for your sin, the God in heaven may forgive you and turn your scarlet red crimes into white as wool. I pray you will spend your remaining days on Earth prostrating yourself before the throne of the most high. You have had a fair trial, and I pray he forgives you."

The judge also complimented the prosecution and the defense for their vigorous efforts.

Judge Johnson continued that Williams would be imprisoned by the sheriff "until the 16th day of May next; on which day, between the hours of 11 o'clock in the forenoon and 2 o'clock in the afternoon of that day, you will be taken by the Sheriff of this County to the place of public execution and hanged until you are dead, dead, dead! and may God pardon your crimes!"

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

While he was awaiting trial, Williams, "in his own hand," had written a story of his life and adventures. (I have been unable to find a copy.)

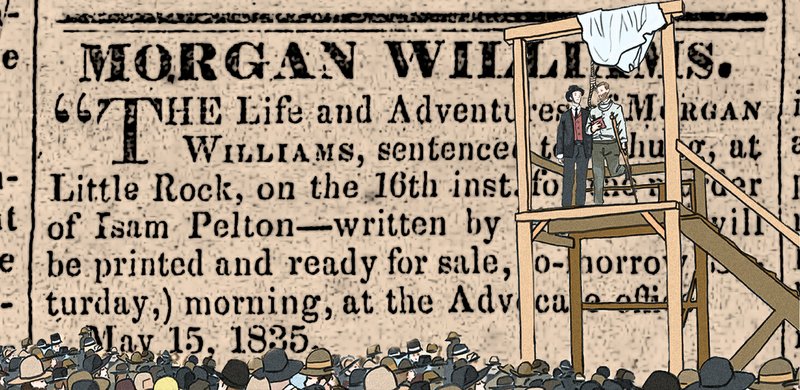

The day before his execution, a small advertisement appeared in the Times and Advocate: for sale at the Advocate office, "The Life and Adventures of Morgan Williams, sentenced to be hung, at Little Rock, on the 16th inst. for the murder of Isam Pelton — written by himself."

The ad appeared four more times, through July. Did Pike feel the need to recover a bit of money for his time as Williams' court-appointed attorney?

LAST WORDS

According to the account in Pike's newspaper, on a spring day, May 16, 1835, Morgan Williams mounted the gallows in the presence of a large crowd and, in a calm and collected manner, read a part of the narrative of his life "in a distinct and impressive tone with no little eloquence."

He met his fate firmly and swung off into eternity at 25 past 1 o'clock, precisely.

The Advocate took the opportunity to editorialize against public hanging: "Public executions do no good but on the contrary is a source of evil in our community. We the Advocate would have criminals executed at midnight and only by the tolling of a bell or the sound of muffled drums should the population know the guilty has expired and a human being went out of the world."

Dee Brown, the Arkansas author of such books as Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, mentioned the hanging in Wondrous Times on the Frontier, written in 1991.

"It was a full scale entertainment event for a large number of spectators," Brown wrote, citing a newspaper account. "Williams began his last words by reading a prepared story of his life. He then made a speech vindicating himself and sang a song he had composed for the occasion. He bade each of his friends a goodbye individually by name.

"All of this required a considerable amount of time but devotees of hangings evidently appreciated long drawn out executions."

Ron Fuller is a former Army officer, former state legislator and lover of Arkansas and military history. He is a member of the Arkansas History Commission and chairman of the Arkansas MacArthur Military Museum Heritage Board.

[RELATED: William Woodruff blamed jailbreak on land pirates]

Style on 01/13/2020