As a private group assumes management today of all four of the state's youth lockups, Arkansas begins a second phase of an overhaul of its long-troubled juvenile-justice system.

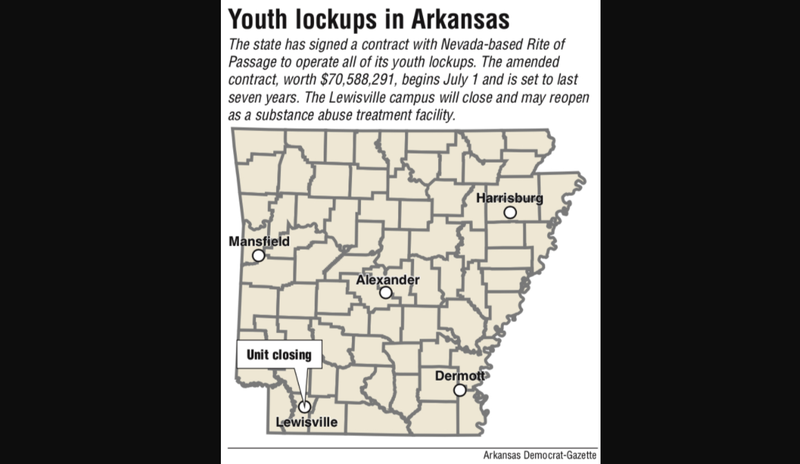

Rite of Passage, a Nevada-based group, officially is taking control of state facilities at Dermott, Harrisburg and Mansfield from Youth Opportunity Investments LLC.

The Rite of Passage firm, which already operated the Arkansas Juvenile Assessment and Treatment Center near Alexander, has a contract for more than $70 million that ends in 2023.

The state at the same time will funnel more funding to community-based services so more kids in trouble can stay close to home, a process called diversion.

State officials also hope the changes will ease youth offenders' transition from lockups back to the community, known as reentry.

Gov. Asa Hutchinson announced the juvenile-justice overhaul in late 2018.

The first phase was focused on improving residential facilities and reducing the number of kids in lockups. The state closed youth facilities at Colt, Dermott and Lewisville. Dermott previously had two facilities.

"When we closed down Dermott, the very first request was for us to take the funds that were utilized and move them into community-based providers," said Keesa Smith, the Arkansas Department of Human Services' deputy director for children, youth and families, speaking of meetings with stakeholders.

Hutchinson said in an email that increased focus on community services has been his goal since the beginning.

"My priority has been to reduce the number housed in faraway facilities and to put the savings in community-based services," he wrote. "I am excited this goal is becoming closer to reality."

Experts have said that treating kids closer to home, outside residential facilities when possible, is the best practice.

In three years, the state has cut the number of children in lockups by about 45% -- from 327 in July 2017 to 179 as of Tuesday.

New money for community services totals $21.43 million for diversion and reentry programs, up from $19.3 million. The changes include:

• $2.27 million for diversion programs to keep children close to home.

• $1.75 million to reentry programs and $1.1 million to vocational and independent living programs. Previously, the Division of Youth Services had $750,000 for one-time funds.

• Regular checks to ensure services are provided.

Under Phase Two, funds will be divided based on the number of youths in an area and the rate of poverty, said Michael Crump, the state's youth services director.

Arkansas' juvenile-justice system has been troubled by problems such as a patchwork probation structure, reported mistreatment of children at facilities, kids detained in the system for longer than recommended and too much focus on discipline rather than treatment.

"I think that we feel that progress has been made, but all the goals certainly haven't been met," said Tom Masseau, executive director of Disability Rights Arkansas, a group federally mandated to monitor treatment of people with disabilities.

Masseau said he thinks funding for community-based services is "a great initiative" for the care of youths, but he added that treatment and reentry plans are only as good as the provider.

He referred to past problems, such as lack of therapy.

His group will follow the Division of Youth Services in the transformation "and make sure that the youth are getting the services that they need," he said.

Crump said he's hopeful that a "floor" in the Rite of Passage contract will help ensure the group can be compensated while the division diverts kids away from lockups. The contract guarantees pay for 194 beds.

When Youth Opportunity declined to renew its annual contract with the state, the company cited financial loss because fewer kids were incarcerated.

Examples of new or expanded programs may include skills or job training, Crump said.

Under Phase 2, providers will have funding available to hire vocational staff members who will work with community colleges and other employers, he added.

The new contracts also encourage increased communication among schools, providers and juvenile-court judges.

In Jefferson County, Judge Earnest Brown of the 11th West Judicial Circuit said his court's teen drug court program will be able to expand, as will job- and life-skill training for all risk levels.

"They had to go to the juvenile judge in their region to talk about diverting children and what they would need to feel comfortable," Smith said.

Judges and providers interviewed by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette expressed optimism about the changes.

Risk levels for whether a child will re-offend are determined through an assessment tool called "Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth," which is required through Act 189 of 2019. Brown said that tool helped him determine what programs were needed.

"We have seen just a tremendous difference," he said in an interview Tuesday.

United Family Services is the community-based provider that covers Jefferson, Pulaski, Perry, Lincoln and Arkansas counties. Lekita Thomas, the group's executive director, said she's excited about programs that teach skills such as budgeting and job interviewing.

"We will be able to offer them to more kids," Thomas said. "We've always tried to have a diverse set of programs to be able to meet more individual needs."

In Faulkner County, Judge Troy Braswell of the 20th Circuit said the community-based provider that works with his court has been able to hire a juvenile-justice advocate to check on kids after hours to ensure they aren't violating probation, and possibly step in if police are called to a child's home.

"They could potentially respond to a domestic disturbance, help calm things down and work with the family to create a safer environment instead of locking the kid up and starting down toward a more punitive path," Braswell said.

The Human Services Department's Smith said that encouraging providers to communicate with school districts about issues as simple as when a child is returning from a state facility is going to be "a major, major focus," of Phase 2. It's one of the changes she hopes will help with reentry.

Braswell touted increased communication as key to reform.

"As a state, we have to continue to work together to help reduce the number of kids that go into DYS, and the way that we do that is through collaboration and through supporting programs that are validated, that work. And that is going to have a long-term impact on the number of adults that are going into prison."

Youth services officials and Hutchinson said there aren't plans in place yet for additional phases.

"It will all be based on how Phase 2 rolls out -- what is successful, what is not successful," Smith said.