It was the right thing to do, and apparently took no persuasion.

Little Rock Major Frank Scott Jr. declared today "Charles Ripley Day."

Rip will lie in state at War Memorial Stadium -- the most fitting of places for him -- from 3-8 p.m. today, and all visitors are required to use social distancing and wear a mask.

Rip, who touched countless lives on a personal level, died Sunday after a long battle with cancer, but his life was always like a country music song: "Live hard, die young and leave a wonderful memory."

When Rip was too tired to work, he worked another hour or two.

When his house was full of boys who needed a safe haven, he'd find room for one or two more.

There was another side to Rip. He was an old-school, bonafide coach who believed you could discipline players, but you had to love them, too.

From the time anyone can remember, Rip was coaching baseball or basketball at the Boys Club.

He rode his bike to the club almost daily.

When he turned 16, his parents bought him a sweet 1956 Chevrolet Bel-Air that most guys would have cut off an arm to own.

For Rip, it was merely transportation. He never was into cars, clothes or romance.

His life was coaching. Anyone who ever played for him -- like Jim Nosari on the old First Pyramid team -- or against him -- like Mike Beard from Lyons Machinery -- realized quickly he coached to win.

In 1964, First Pyramid was a powerhouse of the Pony League. In the last game of the season, they faced W.R. Stephens, another very good team.

Witt Stephens had promised his team a trip to New York for the World Series if the Yankees got there. All they had to do was beat First Pyramid.

It was 1-0 First Pyramid in the fifth inning with two out when the batter for W.R. Stephens got a walk and stole second. The next batter shocked the outfield, which had cheated in, by laying one half way up the dump (that's what the incline was called back then) in center field.

The runner would score, but when the batter slid in to second base umpire John Ross -- who would later become a professional umpire -- called him out at second to nullify the run. He had clearly slid under a desperation attempt at a tag.

First Pyramid won 1-0. As the teams were leaving the field, Rip said to the batter, "I thought you were safe."

The 14-year-old asked Rip why he didn't say something.

"We might not have won," the 18-year-old Ripley said.

Rip graduated from UALR, and his first job was at Forest Heights Junior High to coach football. His quarterback was named Houston Nutt.

Basketball, though, was Rip's first love.

He landed at Little Rock Parkview, and he made the state championship game in 10 of his last 12 seasons as coach of the Patriots.

He won five championships. He's a Hall of Famer.

It would be impossible to name every basketball player who played for Rip, but many received college scholarships because the college coaches knew they were fundamentally sound.

In the summers, Rip would drive to watch his players compete in summer basketball. He didn't interfere, just observed.

It may take the full five hours for all of his admirers -- and many of those who he helped didn't play basketball -- to pay their respects.

In typical Rip fashion, he had one final request. In lieu of flowers, please make a donation to the "Rip It Scholarship Fund" at Arkansas Baptist College.

His dream was to continue his work of educating young people even after he was gone.

Rip was a man who dedicated his life to helping young people, and all he ever asked in return was to be known as coach.

R.I.P, Rip.

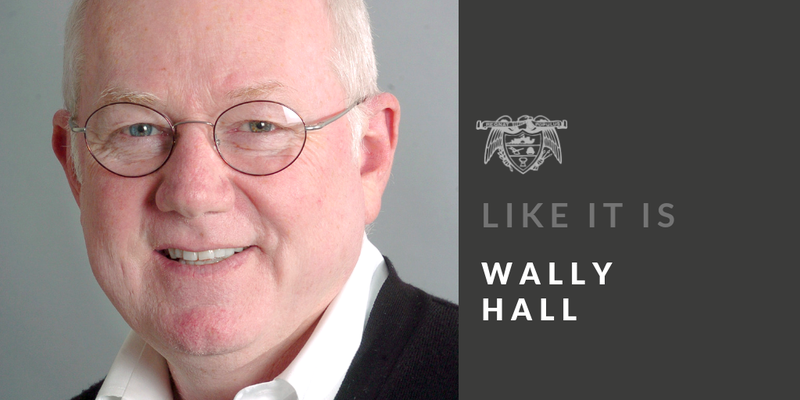

Like it is: Opinion