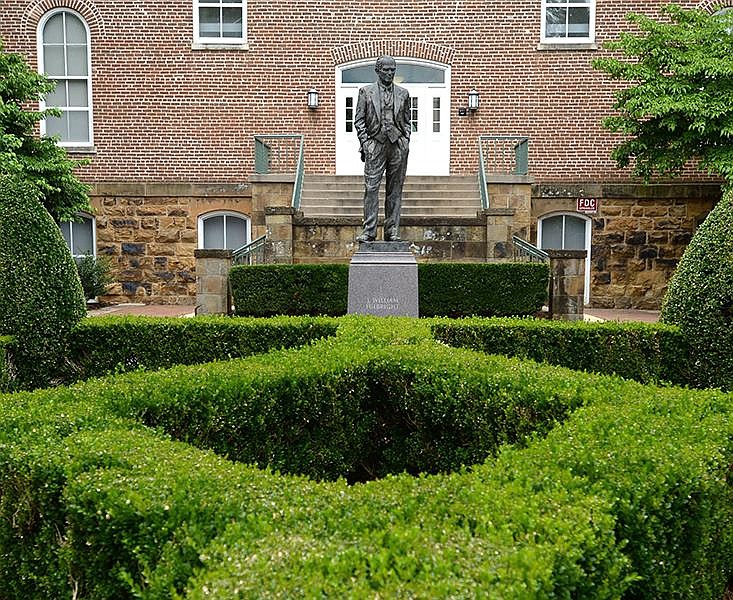

FAYETTEVILLE -- A committee being formed by the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville will consider the removal of a campus statue honoring former U.S. Sen. J. William Fulbright and the removal of his name from the arts and sciences college.

The group will issue a recommendation, but ultimately it's up to the University of Arkansas System board of trustees to decide on any possible changes, Todd Shields, dean of the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences, said Thursday during an online discussion of Fulbright's legacy.

"They have the final decision about naming and public art on the campus," Shields said.

An online petition seeking the removal of the Fulbright statue and the renaming of the college has more than 5,900 signatures.

Fulbright served for 30 years as a senator and is perhaps best known for introducing legislation in 1945 that created the international educational exchange program named after him. The recent petition effort has been promoted by Black student leaders critical of Fulbright's record on civil rights.

The reappraisal of Fulbright comes at a time of reckoning on many college campuses of prominent leaders from the past who promoted racially prejudiced views. Fulbright died in 1995.

"I believe the motivation for the statue was to celebrate Sen. Fulbright's successes in promoting international education," Shields said.

A 7-foot-tall bronze depiction of Fulbright -- not including its base -- was dedicated in 2002. The Fulbright College name dates to 1981, when a $1 million gift to the university was made by the Stephens family. An article in the Arkansas Gazette from that time described Jackson Stephens, then the chairman and CEO of the investment banking firm Stephens Inc., as a longtime friend of Fulbright.

"In exchange for the gift from the Stephens family, the university agreed to name the college after Sen. Fulbright," Shields said.

Shields said the committee is being formed at the request of Chancellor Joe Steinmetz.

Students, faculty members, alumni and staff members "will listen, examine what other institutions have done and are doing, collect information and then deliberate until the committee is ready to make a recommendation" to Steinmetz, Shields said.

Steinmetz will then make a recommendation to University of Arkansas System President Donald Bobbitt, who will then provide a recommendation to the 10-person trustees board for possible action, Shields said. The UA System last week announced the creation of a task force on racial equity.

Asked about Fulbright, UA System spokesman Nate Hinkel said Thursday that it's the system's responsibility to review and make a recommendation to trustees on any issue that would require a decision by the board.

Shields said he and interim provost Charles Robinson -- a historian and former chairman of UA's African and African American Studies program -- are nominating members to the committee.

The committee process "has been successfully used at other institutions making these types of decisions," Shields said.

He also referred to other ideas besides removal, such as bringing to the forefront added context about Fulbright.

"One of the things that I have wanted to do for several years is at minimum contextualize the history, the successes and sins of Sen. Fulbright. I know that it sounds like it's something that'd be easy to do. It was not something that we could get permission to do," Shields said, describing a failed effort that would have involved a public display by the statue and in the Old Main academic building.

'CONTRASTING' LEGACIES

Shields spoke during an hourlong discussion on Fulbright billed as part of an ongoing series known as Fulbright College's Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Hour.

The videoconference Thursday included comments from two historians at UA: Randall Woods and Calvin White Jr.

"What the university community and the state has to deal with is two legacies," said Woods, a Fulbright biographer. "The first legacy is that of a rigid segregationist."

Woods described how Fulbright, a Democrat, opposed civil-rights legislation in the 1960s.

"He voted against the Equal Accommodations Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and even participated in the filibuster against it. He voted against the Voting Rights Act of '65. He voted against the Fair Housing Act of 1968. So his record on civil rights is one of a segregationist Dixiecrat," Woods said.

Fulbright's other legacy includes being "an architect" of the United Nations and creating the education program named after him "that has been the most comprehensive and efficacious exchange program in American history," Woods said.

"He was an outspoken opponent of the war in Vietnam and led hearings which culminated in our withdrawal," Woods said. Books written by Fulbright in the 1960s "were sweeping indictments of the American military-industrial complex" and called for a world "rooted in conflict resolution and peace," Woods said.

With Fulbright, there are "two starkly contrasting legacies," Woods said.

Fulbright "told me that he could not, at one and the same time, champion civil rights and be an enlightened internationalist," Woods said. "His constituency would not stand for that."

But Woods said that, as a historian, he disagreed.

"He had enough political power, he was secure enough, that he could have taken a more aggressive stance on civil rights," Woods said.

Asked if Fulbright ever apologized for his position on civil rights, Woods said he was not aware of any such statement.

"He excused it. He justified it. But he never apologized," Woods said, adding, "not to my knowledge; he certainly didn't to me."

Woods described the university's concern: "Anything that makes students of color feel demeaned, or disrespected, has no place on this college campus or any other college campus. But there is the other legacy. The task before us, it seems to me, is how to repudiate the segregationist legacy while preserving the enlightened internationalist legacy."

HISTORICAL NARRATIVE

White described the history of monuments and statues including post-Civil War efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy that "exploded during the turn of the 20th century."

These efforts honored the bravery of Confederate soldiers but also "romanticized" the Confederate cause in a way that "glorified Confederate patriots and continued to subjugate African Americans to positions of inferiority," White said. Other efforts included exerting influence on schools, with books rejected if they referred to slaveholders as cruel or unjust, for example, White said.

"This became the historical narrative that said many blacks were happy content slaves," downplaying "the terror that was often unleashed on blacks in their community," White said. "In sum, it is easy to see why so many African-Americans take exception to the monuments and statues that are actually dominating our public spaces today. In many ways, it became the Southern white supremacy hidden in plain sight that many African-Americans see."

White also said that others in the past have raised concerns about Fulbright's legacy.

"This debate, while it's difficult to have, it did not catch our office by surprise, and we understand that it is caught up in this national conversation now," White said. "But this is a conversation that I want everyone to be well aware of, that this is a conversation that our team, including Dr. Woods as well, we have been having for a long time."

Among other campuses having a reckoning is Princeton University, which last month announced that it is removing from its public policy school the name of Woodrow Wilson, a U.S. president from 1913 to 1921 who held segregationist views.

White, associate dean of humanities, was asked if the case for removing Fulbright's highly visible association with the campus was "as pressing" as at Princeton involving Wilson.

"Is it as pressing? Absolutely, it is as pressing," White said, calling it "a problem" when anyone walking by the statue may not feel welcome or included.

"Our job is, how do we rectify that problem?" White said, adding that "a knee-jerk reaction will not solve this problem in the long term."

White said that "what we are looking at is trying to solve this long term, to produce a more inclusive and welcoming environment for everyone."