Simply put, had this festival been scheduled a month later, it's very likely it wouldn't have taken place at all. Given the increased proliferation of the coronavirus, and the resulting caution taken by cities throughout the country, there's little doubt the festival, based in Columbia, Mo., would have had to shut it down. Midway through the weekend, word got out that South by Southwest, Austin, Texas' raucous celebration of music and film that takes place later in March, had been shuttered (leaving many journalists scrambling to cancel their travel plans), and the film world now turns its worried attention across the Atlantic to France, where Cannes is seemingly in real danger as well.

The loss of these festivals can be devastating, for myriad reasons. The obvious economic hit affects not just the festival promoters, and deal brokers, but also the bars, restaurants, cafes and nightclubs of the cities in which they take place. There is also the catastrophic effect on the filmmakers, their crowning achievement denied them after months and years of hard labor. For a marketplace festival such as Cannes, where distribution deals are determined over kirs cassis on the French Riviera, it throws the whole business into logjam.

Fortunately, then, True/False just squeezed in before things got more dire, and it's a fine thing they did because this year's edition offered an absolute abundance of fantastic work. Let's break it down, superlative style.

Most Depressing: Welcome to Chechnya. In what is always a crowded field of prime choices at a documentary festival, David France's film about the "gay purge" in Chechnya, where strongman head Ramzan Kadyrov's regime bullies, tortures, and kills suspected LGBT Chechens, and the courageous support groups in Russia dedicated to smuggling the victims out and getting them to safe harbor countries, takes this prize. France peppers the film with intercepted cellphone videos of the violent purge, from bullying and taunting, to rapes, beatdowns, and one potential murder, all of which create a portrait of the horror these victims have to endure under Kadyrov's oppression. Naturally, Kadyrov and Putin deny any such thing is happening, which is why when one young man comes forward to accuse the government formally, he immediately becomes both a cause celeb and one of the most wanted men in Chechnya. Using computer technology to digitally alter the faces of the people trying to escape, France offers a devastating portrait of a country gone mad, under a pair of demagogues with no moral center.

Most Uplifting: Dick Johnson Is Dead. Yes, it's counter-intuitive that a film concerned with the mortality of director Kirsten Johnson's beloved father, who suffers from increasingly disruptive dementia, should also be considered feel-good, but that's the nature of this wonderfully bewitching ode. Johnson, a world-class cinematographer in addition to being a splendid director, treats the film as a means of actually keeping her father alive -- which is why, in a hilariously twisted way, the two of them collaborate to "kill" him onscreen over and over again (a series of accidents and bloody pratfalls involving stuntpeople, special effects, and clever editing). She creates several fantasias, including a version of heaven involving famous people at a banquet table amid many spangles; and a scary, closed-off room of anxiety and horror to represent what it feels like to her affable father to be left somewhere unfamiliar. To keep these more fanciful scenes from being too outlandish, amid an otherwise realistic portrait, Johnson repeatedly takes us behind the scenes during these shoots themselves, so they blend in perfectly with everything else. Culminating in a final turnabout the likes of which leaves one reeling, it's one of the best and most endearingly macabre films of the year. A celebration, of sorts, of what it means to be human and facing our maker.

Most Unsettling: Collectiv. Much as with last year's feel-bad opus, Dark Suns, in which Julien Elie laid out in horrifying detail the ways in which the Mexican government, enjoining with the Cartels, had become thoroughly corrupt, Alexander Nanau's film lays out a similarly unnerving investigation into the hopelessly rotted government of Romania. Beginning with a deadly nightclub fire that initially claimed 27 lives, due to a lack of fire exits to which would-be regulators turned a blind eye, Nanau's film goes on to document the even more disturbing fact that many more of the injured patients died in the hospital's burn wards due to infections they developed because of the criminally diluted disinfectants the staff was using to supposedly render the facility germ free. Following the investigative exploits of a daily sports paper (the only one, apparently, willing to do the work to uncover the truth), it's eventually revealed that the manufacturer of the disinfectant chemicals was purposely watering them down to save money, a practice the hospitals themselves were also following. As if that weren't enough (and it would have been), we come to find even the buying of the chemicals, handled by thoroughly untrained hospital "managers" whose ties to organized crime put them in these crucial seats of power, was also part of the graft. Not to mention the payoffs the nursing staff paid to doctors in order to be assigned to surgeries, where anxious patients offer fat wads of cash to everyone in hopes of staying alive. The picture painted by the end is thoroughly overwhelming, and the kicker, which comes at the very end, seems to ensure another generation will be lost to the same sickening process.

Most Illuminating: The Viewing Booth. Less a film than a filmed thought experiment, director Ra'anan Alexandrowicz continues his thoughtful exploration of the Israel/Palestine conflict (continuing from 2011's informative The Law in These Parts) by challenging himself in the process. Curious to determine how other people react to selected videos concerning the occupation, he sets up an experiment whereby volunteers with some sort of Israel interest or affiliation view one of 40 pre-selected videos (half pro-Israel, half pro-Palestine), as he films their reactions, allowing them to stop and comment along the way. In the process of his first run of seven volunteers, he meets one woman, a college student named Maia Levi, whose parents are Israeli, and leans hard, if not thoughtfully, in the direction of her parents' homeland. Bringing her back six months later, Alexandrowicz then has her observe not only the videos she watched before, but also her initial reaction to them, allowing the two of them to engage in a dialogue in which the difficulty of switching allegiances, or viewing something objectively at all, is truly laid bare.

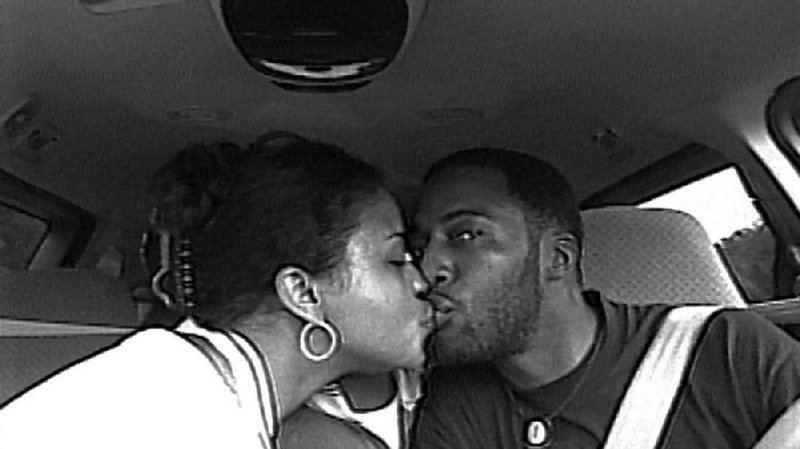

Best Moment: Shared kiss, Time. When it comes around again at the end, the kiss shared by husband Rob and wife Sibil (Fox) Rich feels like a hard-earned crescendo moment for Garrett Bradley's astonishing rumination on the hourglass sands of our lives. Arrested in the '90s for a robbery attempt, the couple both served time, but Rob was hit with the maximum possible sentence of 60 years, while Sibil, not an active participant, was released after a brief stint. While the sentence itself was draconian, and Sibil becomes an advocate for families in similar situations, the film isn't so much concerned with the politics of the case, rather, it focuses on Sibil's efforts to raise their six sons properly, including the twin boys born shortly after Rob gets incarcerated, and also, more philosophically, how the repetitive nature of our time on Earth gets spent with us making choices that either maximize or minimize our experience. Using home movies mostly shot by Sibil as she attempts to raise her sons, start her business, and speak out against injustice, Bradley creates a thoughtful dialectic on the circular nature of our experience. The kiss, originally occurring as the couple are young and filled with promise and optimism, doesn't feel ironic at the end, or a lament of lost opportunity. It's a celebration of closing a loop that stuns you with its unexpected verve.

MovieStyle on 03/13/2020