At 35, Icelandic writer-director Hlynur Pálmason might seem young to be making a movie about grief. A White, White Day is only his second feature.

“I think I’m also at a certain age, 35, where I’m sort of losing the people that I really, really love — my grandparents, and I think this made me want to work on a project like this. So, grief, even though I’m very young, is a big part of my life,” says Pálmason by Skype from his native country.

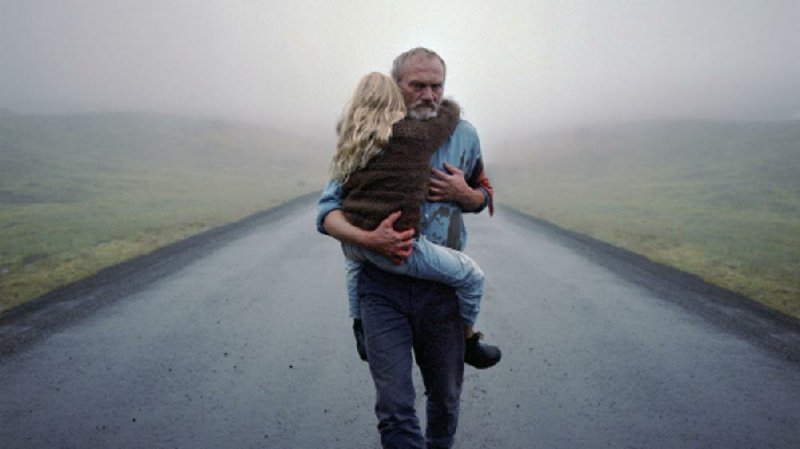

The film, which earned a nomination for the Critics Week Grand Prize at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, is now streaming in the United States. A White, White Day stars Ingvar Sigurdsson as Ingimundur, a policeman struggling to deal with the aftermath of a car wreck that killed his wife. While he tries to rebuild his life without her, Ingimundur is also disturbed by the possibility that the woman he devoted life to was unfaithful.

This inner struggle leads to physical neglect toward his own home and emotional disturbances in dealing with the people in his life. Counseling doesn’t seem to help Ingimundur because he angrily demolishes the computer monitor that allows him to see his livestreaming therapist. While this sort of turmoil is awful to live with, it’s been rewarding for Sigurdsson, who won Louis Roederer Foundation Rising Star Award at Cannes for his performance, which includes the unique way of dealing with computer hardware.

Pálmason explains that Ingimundur’s outrageous behavior comes from observation.

“The world is often much crazier than fiction,” he says. “The Skype thing comes from a real event, a real thing I heard from a friend. Often it comes from a real event. I fall in love with all my characters. I think we are capable of doing all kinds of things. Some people think he’s a little too rough. Some people understand him. I think it’s different for each individual.”

Perhaps audiences can tolerate the outbursts because Ingimundur has a close relationship with his granddaughter Salka (Ída Mekkín Hlynsdóttir). “I feel personally that children are the most interesting people around. They’re very genuine. The world hasn’t changed them or spoiled them. They’re truthful in a way. You can see a lot of humanity with them. That can have a healing effect on a person, being with someone who is just fun being around with,” Pálmason says.

With a population of 364,000, there’s not a large supply of child actors in Iceland, but as Hlynsdóttir’s patronymic surname implies, the director didn’t have to look far to find someone to play Ingimundur’s granddaughter.

“It’s not an easy [role] that I wrote for her,” her father and director explains. “There were a lot of things that were difficult to come to and do emotionally, screaming and crying things that are not something you do every day. It’s important that it’s a collaboration and that the actors really want to do it and find it interesting and stimulating and [want] to take a chance and are not afraid of failing or looking silly. It’s important there are people around you who love the project and are willing to take a chance.”

In fact, Iceland’s small labor pool offered Pálmason some advantages.

“My crew is very tight. I haven’t made many films, but we’re good friends and family. My set is very, very different from a traditional movie set in America. It’s even different from a movie set in Europe. It’s quite small,” he says.

“It has been said there are a lot of artists living in Iceland compared to the Icelandic population. I think we have a very old tradition with the Icelandic sagas and literature. We have a very strong fundament for storytelling. We try to nurture that. With the filmmaking world, we’re basically just children within the film world because I think the first feature film was made in 1969. We have been nicely exposed over the last couple of years, and our films are being shown all over the world.”

Time and Land

One sequence that couldn’t have been shot on this side of the Atlantic is a sequence near the film’s opening where we see Ingimundur’s home in a series of wide shots of the change of seasons. Until Salka comes to visit, his damaged outer fence remains torn even though he keeps animals on his property. Before viewers even get to know Ingimundur, there are already signs of the disorder in his life.

“Time is very much the medium your working with when you’re working with cinema. You have a certain amount of minutes, and you try to create an experience. I’m interested in the seasons and the contrasts of something being cold or warm or brutality and beauty being put together. The prologue of the film took me two years to film, but while I was filming it, I was researching it and sort of prepping the film. I work parallel on a couple of projects. I try to draw them out so they take more time,” Pálmason says.

The film also begins with an old quote from the nation about how the sky and earth become one, which makes contact between the living and the dead more likely. As if to prove the saying’s veracity, the film’s opening shots show a car moving through a landscape where the ground and the heavens are indistinguishable.

“It’s a place that I’m very fond of. It’s a mysterious place. It’s the highest gravel road in Iceland. Every time I drive down that road, I think it’s very, very beautiful but very, very eerie. It sort of stimulated me and made me think of this quote,” he says.

“I’ve lived in a city [the director is Danish educated], but I’ve never made a film in the city. I don’t know why that is. Maybe I need to live there more time to get sort of soaked in it. Out in the landscape, you are more part of the weather. You’re much close to nature and the mysterious side of it.”

Balancing Act

A White, White Day might deal with grim subjects like grief and violence, but often Ingimundur’s frustrations lead to moments of quirky comedy. Pálmason freely admits his fondness for Buster Keaton’s 1924 silent comedy Sherlock Jr.

In the film, Keaton carries around a book titled How to Be a Detective, and like Ingimundur is trying to correct a situation where he has been wronged. Nonetheless, it’s hard to imagine Keaton shoving two fellow cops into jail cells when he becomes upset with them.

“When I was writing it, I remember people asking me about that scene,” Pálmason says. “‘Are you sure about it? Does it even make sense?’ But I felt very strongly that it would make sense in this world we were creating. Things work if they are in context. Sometimes you push it too far, and it tips over and doesn’t work. Film for me is very much about that balance.”