Let's stipulate that social media is filled with pyrrhic arguments and scams and attention seekers. On the internet, no one knows you're a dog, but jerks have a way of immediately outing themselves.

But if you don't enjoy social media, you might be doing it wrong. I find it useful and entertaining, especially in these days of house arrest. It is genuinely possible to have intelligent conversations, it is possible to find something like community there.

Through my Facebook feed, I connect with people who hold strong opinions while remaining open to fresh avenues of delight. Social media can be a kind of an online salon without the obligatory small talk.

The other day an FB friend posted a YouTube link to Rod Stewart's song "Seems Like a Long Time," a track off Stewart's third solo album, 1971's Every Picture Tells a Story, along with the question: "Remember when Rod Stewart was really, really good?"

That kicked off a modest 38-comment thread about Stewart's remarkable early career, with most counting his work with Jeff Beck, the Faces and his first three solo albums as "really, really good," which is more restricted than the conventional notion that Stewart stopped being "really, really good" when he signed with Atlantic Records in 1974.

We say that's the conventional wisdom, but only among a certain elite audience — a lot of people on the thread spend their lives thinking and writing about rock music. All the commentators were conversant with the judgment of Greil Marcus, one of the most perceptive writers ever to take up the subject of rock 'n' roll: "Rarely has a singer had as full and unique a talent as Rod Stewart; rarely has anyone betrayed their talent so completely."

Most of the commentators are old enough to have experienced Stewart's early career in real time; they had Stewart's records when vinyl copies were the only option.

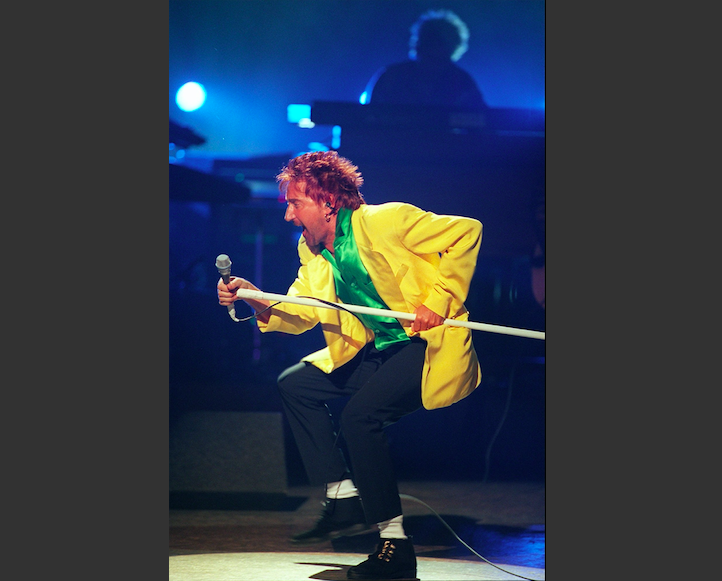

To many, Stewart is the platonic ideal of a rock star. He had a lot of hits, an unmistakable, highly polarizing voice and made a lot of money when it was still possible to make a lot of money in the music industry.

But for a few of us, Stewart's story is tragic. Not for him, but for me. Because there was a time when he made some of my favorite music ever. Then he stopped, just about the time he became the embodiment of jet-set rock-star millionaire.

Robert Johnson may have sold his soul to the devil to acquire genius; in the mid-1970s, Stewart threw his genius away for a parody of rock stardom. Sure, he's got a Mercedes-Maybach and a private jet, and more money than his children's children can ever spend, but he's generally known for wearing tartan, kicking soccer balls into concert audiences, Spandex, serial suicide blondes, "Do Ya Think I'm Sexy?" and the shamelessness of his half-hearted shambling through the "Great American Songbook."

There was a time when he was a genuinely great artist.

. . .

Rod Stewart was 23 years old in 1968, and he'd been around.

He'd aspired to be a footballer — a soccer player — but he wasn't quite professional quality. He left school at 15, worked as a gravedigger, had other odd jobs and was the lead singer of the Raiders, who scored an audition with legendary producer Joe Meek in 1961. When they began to play, Meeks put his fingers in his ears and screamed until Stewart shut up.

He produced some sides for the band, which he renamed The Moontrekkers, but only allowed them to play instrumentals. (Meek also famously advised Brian Epstein not to bother signing The Beatles after hearing their demo tapes. And he murdered his landlady with a shotgun before killing himself. One of the greatest record producers in British history was also a murderous and allegedly tone-deaf schizophrenic.)

But Stewart was undeterred. He sang on the streets of London, Paris, Barcelona — he was deported from Spain for vagrancy in 1963 — and he might have become lead singer for a nascent version of the Kinks had drummer John Start's mother not objected to his voice (the band rehearsed in the Start garage, so mum had veto power).

He was scouted by Decca Records as early as 1964 but saw himself as more a rhythm & blues singer than the pop singer they envisioned. Stewart's lodestar was Sam Cooke.

He did a stint with Long John Baldry's Hoochie Coochie Men. Then with a band called Steampacket that never recorded. As a session singer for hire, he appeared uncredited on Australian band Python Lee Jackson's single "In a Broken Dream" (which was recorded in 1968 and became a hit in 1972, after Stewart's raspy voice had become unmistakable).

Then Beck recruited him for his post-Yardbirds Jeff Beck Group to be the vocal foil for his guitar on the albums Truth (1968) and Beck-Ola (1969). While it was still work for hire, the JBG's material — mostly blues, folk and rock standards with the occasional twist (such as Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II's "Ol' Man River") — was a good fit for Stewart's burgeoning sensibilities. It was also with Beck that he first played with guitarist Ronnie Wood, who he'd known since 1964.

While a part of the Beck group, Stewart continued to pursue a solo career, releasing the odd single on minor league labels. He was beginning to understand that what he really wanted to do was make his own music — he co-wrote three of the songs on Beck-Ola. Mercury Records producer Lou Reizner signed Stewart to a solo deal in 1968, and when Wood left the JBG, Stewart soon followed.

When Steve Marriott left the Small Faces in May 1969, the band suddenly needed both a guitarist and a singer. Wood took over as guitar player in June, and Stewart joined the band as lead singer in October. Small Faces became Faces, because Stewart and Wood were both considerably taller than Marriott.

Stewart's first solo record, An Old Raincoat Won't Ever Let You Down (titled The Rod Stewart Album in the U.S.) was produced by Reizner in collaboration with Stewart. It employed Wood and two guitarists from British blues band Steamhammer, Martin Pugh and remarkable acoustic player Martin Quittenton. Faces keyboardist Ian McLagan played piano and organ. Jeff Beck Group drummer Mickey Waller played drums. Keith Emerson played organ on one track.

The record begins with a version of the Rolling Stones' "Street Fighting Man" that serves as a kind of keynote to "the good Rod Stewart."

Like the Stones' version, this Old Raincoat track is primarily acoustic, with Wood's bass being the only electric instrument, but Stewart's version turns the Stones' song inside out structurally, rendering the hard rock into a kind of Band-ish folk rock.

But Stewart's folk rock was different from the mid-'60s model where folk songs were re-imagined with electric guitars "Turn, Turn, Turn" style: he used folk textures, mandolins, fiddles, pedal steel and bottleneck guitars to take rock songs back home.

This same approach, and largely the same musicians, carried through with Gasoline Alley (1970) and Every Picture Tells a Story (1971), augmented by Stewart's remarkable growth as a writer capable of compassion and uncommon tenderness.

Stewart found his metier as the everyday bloke yearning for a decent kind of life, aware that he was capable of hurting people and being hurt. Surprisingly, given the outsize persona he would soon adopt, Stewart's first three solo albums were tasteful. As impossible as it seems, given Stewart's coming Hollywoodization, they were modest, heartfelt and deeply sincere.

At the same time, Stewart was part of a bombastic rock 'n' roll band, making some of the greatest rock 'n' roll party records of all time. The Faces were the Replacements of the early '70s, drunk, loud, heartbreaking, vulnerable. The Stewart-fronted Faces can go toe-to-toe with the Rolling Stones of the same period. But, while worth celebrating on its own merits, that's a different discography. The Faces albums were fun but mainly served to build anticipation for what came next.

. . .

Most people were introduced to Stewart by "Maggie May," a no-chorus-having ramble he wrote with Quittenton and considered leaving off Every Picture Tells a Story. It made him a star on both sides of the Atlantic (the LP and its single "Maggie May" topped the U.S. and U.K. charts simultaneously, the first time that had ever happened).

It's one of the best rock records ever made: drums, bass and acoustic guitar filigreed with that beautiful mandolin solo he bought off a session player named Ray Jackson for 15 pounds. (Jackson, who'd been hired to play on Stewart's "Mandolin Wind," came up with the mandolin hook on "Maggie May" after the rest of the track was recorded. In the album's liner notes, he wasn't credited, but Stewart wrote the "mandolin was played by the mandolin player in Lindisfarne. The name slips my mind.")

For some of the commentators on the thread, that was about the time Stewart started to sell out, a process completed by his move to Warner Bros. from Mercury (and to the U.S. from the U.K.) in 1975.

But his 1972 solo record for Mercury, Never a Dull Moment, is of a piece with those early albums, probably not quite as good as Every Picture Tells a Story but better than the debut and Gasoline Alley.

And while 1974's Smiler is a weaker effort, it's because the material is weaker, not because the performances are any less earnest. Stewart's approach does seem to be sliding a little toward formula and his re-gendered cover of Aretha Franklin's "Natural Woman" ("Natural Man") is a miscalculation.

While Stewart was less consistent on his new label, both 1975's Atlantic Crossing, produced by Tom Dowd and recorded in part at Muscle Shoals Sound in Alabama, and 1976's A Night on the Town have some really good moments, such as "The Killing of Georgie" and Stewart's version of "The First Cut Is the Deepest."

Stewart was really good up until A Night on the Town, but there are good reasons to draw a bright line between the pre-1974 recordings he made as a solo artist for the Mercury label, with the Faces and the Jeff Beck Group and his post-1975 solo career with (almost exclusively) Warner Bros.

Let's note how busy Stewart was from 1968 to 1974 — during that period, he recorded two albums with the Jeff Beck Group , five with the Faces (First Step, Longplayer, A Nod Is As Good As a Wink ... to a Blind Horse, Ooh La La, and the live set Coast to Coast: Overture and Beginners, credited on release to "Rod Stewart/Faces") and five solo albums.

Throw in the compilation album Sing It Again, Rod, and that makes 13 album in seven years, which even 50 years ago was a lot of product for the market to absorb.

But not all of it is really, really good. Stewart's voice — a whisky-soaked tenor croak with frayed ends that crackle and drag — is probably the best instrument ever bestowed on a male would-be singer of rock 'n' roll, rhythm & blues and freighted acoustic folk, but it wasn't always put in service of great material, even on his own albums.

When Stewart was singing material worthy of that magnificent instrument — "Every Picture Tells a Story" or "You Wear It Well" or "Gasoline Alley" — he was making some of the greatest vocal pop music of all time.

Stewart is a great interpreter — witness his resuscitation of Ewan MacColl's "Dirty Old Town" and his claim-staking version of Mike d'Abo's "Handbags & Gladrags." And he remains such. Not even his half-hearted shambling through the great American songbook is terrible.

But what changes when he goes to Warner Bros. is that he's no longer working with his mates in the studio but with a bunch of hired guns who are virtuoso studio pros. And he's no longer as involved in the production, hiring out big names. A lot of intimacy and inspiration bleeds away. Stewart's songwriting suffers — before 1975, he wrote specific vivid songs studded with detail: not just "Maggie May" and "You Wear It Well," but "Blind Prayer," "An Old Raincoat Won't Ever Let You Down" and "Cindy's Lament."

After 1975 came "Do Ya Think I'm Sexy" and "Blondes Have More Fun," with lots of co-writers and proto-David Lee Roth posturing. Fine. While Stewart's voice could still arrest one's attention, he seemed more interested in presenting as a decadent playboy than as the genuinely great artist he once was.

"I was only joking."

Now he tells us.

. . .

Don't get mad at Stewart.

He probably never had any aspiration to become a great artist.

He became a great artist to get rich and pull birds. And, mission accomplished, he became Rod Stewart. He didn't betray us, he only betrayed his gift. And how he apprehended that gift is a mystery we can't penetrate.

He probably doesn't write songs like he used to because he can't do that anymore. Lots of us can't do things we used to be able to do. All artists change. Sometimes, as with Paul Simon and Nick Lowe, they get better as they get older. But not usually.

Stewart didn't. But I remember when he was really, really good.

Email:

pmartin@adgnewsroom.com

Style on 05/17/2020