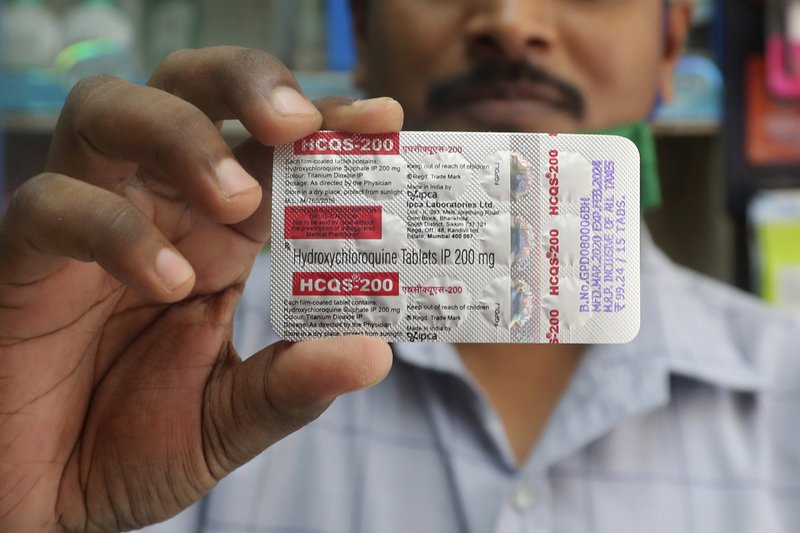

Malaria drugs did not help in the treatment of covid-19 and were tied to a greater risk of death and heart rhythm problems in a new study of nearly 100,000 patients around the world.

Friday's report in the journal Lancet is not a rigorous test of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, but it is the largest look at their use in real-world settings, spanning 671 hospitals on six continents.

"Not only is there no benefit, but we saw a very consistent signal of harm," said one study leader, Dr. Mandeep Mehra, a heart specialist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

Researchers estimate that the death rate attributable to use of the drugs, with or without an antibiotic such as azithromycin, is roughly 13% versus 9% for patients not taking them. The risk of developing a serious heart rhythm problem is more than five times greater.

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

Separately on Friday, the New England Journal of Medicine published preliminary results of a study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health of remdesivir, a Gilead Sciences drug that is the first to show any evidence of benefit against the coronavirus in a large, rigorous experiment.

As previously announced, in a study of 1,063 patients sick enough to be hospitalized, the drug shortened the time to recovery by 31% -- 11 days on average vs. 15 days for those given usual care. After two weeks, about 7.1% of those on the drug had died vs. 11.9% of a comparison group given a placebo. Researchers will track the patients for another two weeks to see if death rates change over time.

A statement from the NIH says the results support making the drug standard therapy for patients hospitalized with severe disease and needing supplemental oxygen -- the group that seemed to benefit most. The drug is not yet approved, but its use is being allowed on an emergency basis.

The study of the malaria drugs was less rigorous and observational, but its size and scope gives it a lot of impact, said Dr. David Aronoff, infectious diseases chief at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

"It really does give us some degree of confidence that we are unlikely to see major benefits from these drugs in the treatment of covid-19 and possibly harm," said Aronoff, who was not involved in the research.

TRUMP DISAGREES

Trump has said he is taking hydroxychloroquine to try to prevent infection or minimize symptoms from the coronavirus.

Twice this week, Trump has not only dismissed the findings of studies but suggested that their authors were motivated by politics and out to undermine his efforts to roll back coronavirus restrictions.

First it was a study funded in part by the NIH that raised alarms about the use of hydroxychloroquine, finding higher overall mortality in coronavirus patients who took the drug while in Veterans Administration hospitals.

He offered similar push-back Thursday to a new study from Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. It found that more than 61% of covid-19 infections and 55% of reported deaths -- nearly 36,000 people -- could have been been prevented had social distancing measures been put in place one week sooner.

"Columbia's an institution that's very liberal," Trump told reporters Thursday. "I think it's just a political hit job, you want to know the truth."

Undermining Americans' trust in the integrity and objectivity of scientists is especially dangerous during a pandemic when the public is relying on its leaders to develop policies based on the best available information, said Larry Gostin, a Georgetown University law professor who is an expert in public health.

"We have every right to expect that our leaders will use the best science to keep us safe and protect us," Gostin said. "And so the idea that you reject objective scientific information that could inform policies that have life-or-death consequences is unfathomable."

The White House rejected that thinking, noting that Trump has followed his administration's public health officials' recommendations through much of the crisis.

"Any suggestion that the president does not value scientific data or the important work of scientists is patently false as evidenced by the many data-driven decisions he has made to address the covid-19 pandemic, including cutting off travel early from highly-infected populations, expediting vaccine development, issuing the 15-day and later 30-day guidance to 'slow the spread,' and providing governors with a clear, safe road map to opening up America again," White House spokesman Judd Deere said.

SIDE EFFECTS EMPHASIZED

The drugs are approved for treating lupus and rheumatoid arthritis and for preventing and treating malaria, but no large rigorous tests have found them safe or effective for preventing or treating covid-19. People sick enough to be hospitalized with the coronavirus are not the same as healthy people taking the drugs in other situations, so safety cannot be assumed from previous use, Mehra said.

These drugs also have potentially serious side effects. The Food and Drug Administration has warned against taking hydroxychloroquine with antibiotics and has said the malaria drug should be used for coronavirus only in formal studies.

Lacking results from stricter tests, "one needs to look at real-world evidence" to gauge safety or effectiveness, Mehra said. The results on these patients, from a long-established global research database, are "as real-world as a database can get," he said.

His study looked at nearly 15,000 people with covid-19 getting one of the malaria drugs with or without one of the suggested antibiotics and more than 81,000 patients getting none of those medications.

In all, 1,868 took chloroquine alone, 3,783 took that plus an antibiotic, 3,016 took hydroxychloroquine alone, and 6,221 took that plus an antibiotic.

About 9% of patients taking none of the drugs died in the hospital, vs. 16% on chloroquine, 18% on hydroxychloroquine, 22% on chloroquine plus an antibiotic, and 24% on hydroxychloroquine plus an antibiotic.

After taking into account age, smoking, various health conditions and other factors that affect survival, researchers estimate that use of the drugs may have contributed to 34% to 45% of the excess risk of death they observed.

About 8% of those taking hydroxychloroquine and an antibiotic developed a heart rhythm problem vs. 0.3% of the patients not taking any of the drugs in the study. More of these problems were seen with the other drugs, too.

The results suggest these drugs are "not useful and may be harmful" in people hospitalized with covid-19, professor Christian Funck-Brentano of the Sorbonne University in Paris wrote in a commentary published by the journal. He had no role in the study.

Information for this article was contributed by Jill Colvin and Carla K. Johnson of The Associated Press.

A Section on 05/23/2020