After four years of bitter partisan feuding over its investigations into President Donald Trump, the House Intelligence Committee is facing perhaps its steepest challenge yet: restoring bipartisan functionality to the panel that is supposed to be Congress' first line of defense against the nation's most existential threats.

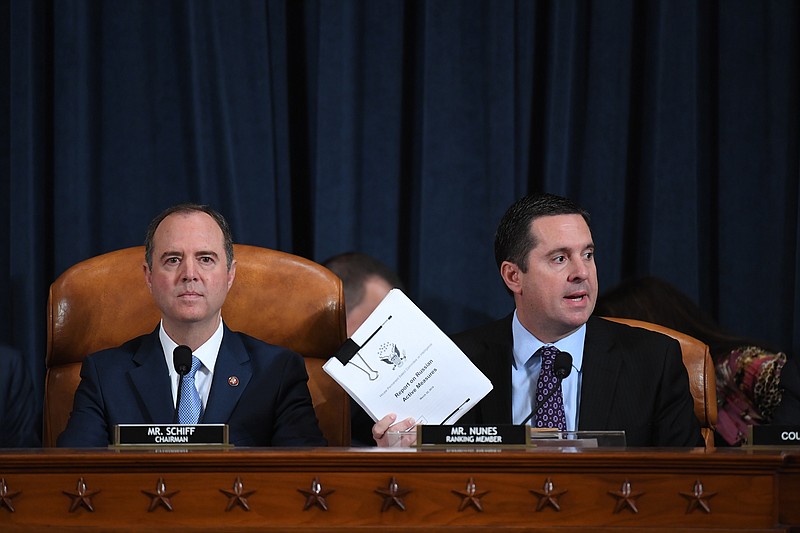

Back-to-back Russia probes and an impeachment investigation soured the committee's traditionally apolitical culture and catapulted its leaders into the sharply partisan limelight as they defended or excoriated Trump. As Democrats accused top Republican Rep. Devin Nunes of California of conspiring to protect the president, and Republicans accused top Democratic Rep. Adam Schiff of California of making up lies to smear him, each assumed the joint role of hero to his party and boogeyman to the other side -- and the panel became the scorched earth in between.

Even after investigations cadenced, scars remain. For months, Republican members have boycotted all but one of the committee's public events, as well as unclassified private briefings. The panel also has yet to produce a single piece of legislation or statement of policy that has not split along party lines.

"There's a part of me that thinks it's almost biblical, like Moses, and that generations are going to have to come and die out before everything is cleansed," said Rep. Mike Quigley, D-Ill., a member of the panel. "But there are still things that are bipartisan: threats to national security, homeland security. ... Heaven forbid something dramatic happens, which tends to be a unifier. And then it's really up to people to decide to move on or not."

Democratic and Republicans panel members expressed a common hope that, in a post-Trump Washington, the committee could restore a less-divisive work ethic. But more often than not, that hope was coupled with feelings of futility and finger-pointing across the aisle.

"Not with Adam Schiff as chair," Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-N.Y., answered when asked if the panel could set aside differences. "He has politicized and broken that committee, he has overseen a committee that has leaked like a sieve, and it's a toxic, toxic environment because of Adam Schiff's failure of leadership."

Rep. Denny Heck, D-Wash., who is retiring at the end of the year, offered a similar assessment of Nunes.

"There's a rumor that Mr. Nunes is trying to become the ranking member of Ways and Means. ... If he is successful, we'll have a chance to hit the reset button, and I think that would be healthy for everybody," Heck said. "I don't think there's any constructive purpose in this point about pointing the finger. ... I just have my fingers crossed that there will be a change so we can return to some state of bipartisanship."

Schiff is expected to remain chairman next year, and nearly all the Democrats on the committee are expected to return in the new Congress. Republicans already have at least three slots to fill due to members who have or will be retiring, regardless of whether Nunes inherits the top GOP slot on another panel, and they could add a seat to their roster to reflect the party's gains in the election.

A spokesman for Nunes did not respond to a request for an interview. But Schiff said he would be a "willing partner" in moving the committee beyond its discord, provided Republicans were willing to meet him halfway.

"The minority over the last few years viewed themselves not as an oversight body, but essentially defense counsel for the president ... so I think the minority only has itself to blame for the poisoning of the relationship," Schiff said. "We are extending a hand, notwithstanding that history."

Schiff acknowledged that "it'll take time to restore trust," both between the two parties and between the panel and the intelligence agencies, but expressed confidence that "it can be done."

"A lot of the areas of friction will have departed along with the Trump administration," Schiff added.