In 1978, the Blues Brothers album "Briefcase Full of Blues" topped the Billboard charts, "Animal House" became the highest-grossing comedy to that point, and "Saturday Night Live" soared to a new high in the ratings. These jolts to American pop culture shared one thing: the norm-shattering, can't-look-away whirlwind known as John Belushi.

Four decades on, memories of this human dynamo are often overshadowed by Belushi's death in 1982 from a drug overdose at age 33. Director R.J. Cutler's new documentary, "Belushi," on Showtime, aims to right that ratio, creating an intimate portrait of Belushi as a fully fleshed-out man while emphasizing his oh-so-vivid life over his terrible death.

"One of the important aspirations was to capture the lightness and the joy that John not only experienced but that he brought to the world," Cutler says. He hopes Belushi's longtime fans discover he "was more than just an awesomely funny guy and fearless comedian," he says.

"He was a writer, a director and a visionary," Cutler continues. "He was forever reinventing himself and forever stretching."

Opening with Belushi's "SNL" audition tape, in which he flaunts his expressive eyebrows and does his Marlon Brando impression, the movie captures his charisma immediately. "John had that connection with the audience where they could see right into his heart," Lorne Michaels, the "SNL" creator who hired him, with some trepidation, says in the film. "There was so much vulnerability that you thought you knew who he was."

A COMPLEX PORTRAIT

Family interviews and love letters to his future wife build a complex portrait of his early life as the ambitious son of an Albanian immigrant, hinting at the success and difficulties to come.

"John was his own kind of comic genius and also an Everyman," says Sean Daniel, a Universal Pictures executive on "Animal House" who bought "The Blues Brothers" movie after a phone call with Belushi and his co-star and former "SNL" castmate, Dan Aykroyd.

"John had a true exuberance, and it informed his performances," Daniel adds. "But he took his work really seriously and was every ounce a creator, a real artist."

The documentary was a long time in the making; in fact, its first seeds were planted with the 1984 Bob Woodward book about Belushi, "Wired," which his widow, Judith Belushi Pisano, and many friends and family members viewed as a sensationalist and distorted view of the actor's life. In response, Belushi Pisano began recording interviews with Belushi's friends and family, hoping to someday present a different view.

For nearly two decades, Belushi Pisano sat on those tapes before deciding to bring in a friend, writer Tanner Colby, to collaborate on an oral biography. To that already rich trove of material Colby added new interviews with people like Michaels, Robin Williams, Christopher Guest and Carrie Fisher, which the two assembled into their book, "Belushi: A Biography," published in 2005.

Shortly after the book came out, Belushi Pisano met documentary producer John Battsek, who said that he would love to tell Belushi's story on film. She said no.

"What was holding me back was my second marriage," she recalled. "I didn't think it would be a good thing for me again to be putting my time and attention to my late husband."

Battsek was undeterred, calling every six months, always graciously accepting her "Now's not the time" response. "I felt really passionately that there was a great story to be told, not just a tragic story," Battsek says, "with enough complexity to make a really interesting film."

SOMEONE ELSE

Then in 2015, five years after divorcing her second husband, she finally said yes ... to someone else.

Oscar-winning documentary producer Bill Couturié pitched a film idea and said he would bring in Daniel, the executive who bought "The Blues Brothers."

"So I said, 'This is kismet,'" Belushi Pisano recalls (although she wasn't thrilled with Couturié's original concept, which was a docudrama with re-enactments). Shortly after, Battsek checked in.

"When I heard John's voice, I said, 'Oh, my god, I can't believe I didn't talk to him before I did this," Belushi Pisano remembers about her conversation with Battsek. "We had become quite friendly by then."

Battsek "was devastated," he says, but he kept calling. When the project stagnated without financing, he persuaded them to hand over the reins to produce if he could quickly obtain backing. Showtime, for whom he had just produced "Listen to Me Marlon," a documentary based on Marlon Brando's personal tapes, immediately signed on. (Couturié and Daniel stayed on as executive producers.)

To direct, Battsek brought in Cutler, a fellow producer on the Brando documentary, who had already directed documentaries on Oliver North, Anna Wintour and Dick Cheney and had a good relationship with Showtime. Cutler set to work, unaware of the trove of tapes and letters amassed by Belushi Pisano and Colby. His initial conversations with Belushi's friends and colleagues frustrated him.

"Some stories were lost in the foggy haze of memory, and some felt like they were merely telling their 'John Belushi stories' and they were performative," Cutler says. "How I would bring this story to life became a big question."

A BELUSHI MUSEUM

Cutler cracked the conundrum when he and Battsek visited Belushi Pisano's home in Martha's Vineyard. She showed them her basement room that Battsek describes as a Belushi museum. "It's one of those out-of-body moments. There's the original, typed-out cheeseburger skit" from "SNL," he says. "And she had all these letters and all the audiotapes from those interviews."

The letters Belushi had written to her (read in the film by Bill Hader) offered a rare glimpse into a private man who gave away little to the media. But the cache of recorded interviews with friends and family were "the key that unlocked the riddle," Cutler says. "They were raw and had an immediacy."

Belushi Pisano turned over the material and put her trust in Cutler, but she worried about the family getting hurt again. Jim Belushi, the most famous of John Belushi's three siblings, was nervous but not hesitant.

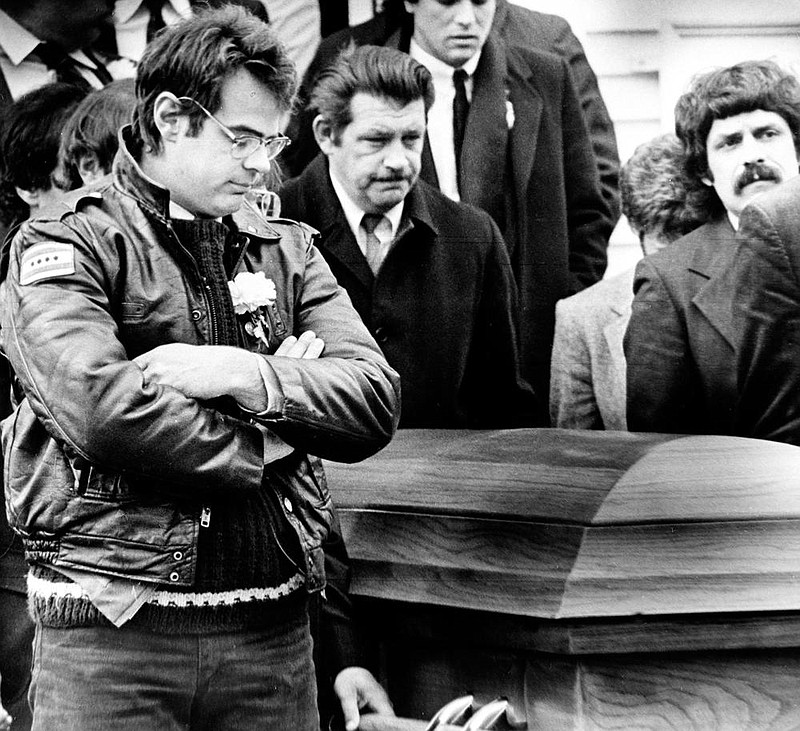

"I'm always wary," he says, toward anybody who wanted to dig into his brother's life. "But I support Judy," he adds, "in any decision she makes about her husband. All I said to Judy was, 'Please tell them not to show the body coming out of the [expletive] hotel.'"

In the finished film, friends and former colleagues including Aykroyd, Fisher and Harold Ramis are heard recounting the good and bad times, often accompanied by animation; Fisher talks unflinchingly about how for someone without the proper coping skills and support groups, sobriety can be more hellish than addiction.

DIFFICULT SIDE

The film doesn't shy from Belushi's difficult side. He could be moody and unreliable, picking fights with "SNL" castmates,showing up late or missing work. He could be insecure, racked with jealousy when Chevy Chase became the show's first breakout star. In one segment, Belushi's castmate Jane Curtin and others are heard criticizing his attitude toward female colleagues. ("It was difficult working with John," Curtin says in the film. "He didn't seem to respect the women on the show.")

In recordings, Michaels recounts their tumultuous work relationship on "SNL." By Belushi's fourth and final season, as stardom and drug abuse took its toll, Michaels appears to have reached his limit. When a doctor told him one Saturday that there was a 50-50 chance Belushi would die if he performed that night, Michaels recalls in the documentary, he replied, "I can live with those odds."

Unlike the Woodward book, which seemed eager to dive into the image of Belushi as a hard-partying druggie, the movie frames Belushi's final days more as what Battsek described as "a fight he's having with the drugs; he's in so much pain, but there's an inability to stop." We read Belushi's desperate, heart-rending letters to Belushi Pisano ("I'm afraid I'm too far gone") as he was swallowed up by addiction. We hear Aykroyd's regret-filled remembrances. We listen to Belushi's mournful rendition of the song "Guilty," singing, "It takes a whole lot of medicine for me to pretend to be somebody else."

Jim Belushi says he was largely happy with Cutler's telling. "I'm just so thrilled because finally they explored who John was, his talent, his struggles, his drive," he says, "and then the last half-hour was just heartbreaking. I cried my eyes out.

'INSPIRING BEGINNINGS'

"The feelings you have watching the last half-hour I've been sitting on for decades," he continues. "But what I really liked about it was that they muted the sensational aspects of the end and lean into the inspiring beginnings."

Belushi Pisano mostly agrees but still felt the movie was too heavy. "John thought his purpose on earth, his talent and his gift, was that he could make people laugh and feel good," she says. "I feel the weight of sadness overall in the film, and I don't think that represents his life so well."

Cutler understands that everyone brings a unique perspective: "Judy's response is 100% valid," he says. "I'm not trying to please anybody; I'm making a work of art that's going to speak to everybody in a very specific way."

In the end, Belushi should be remembered for performances that were timeless but captured the anarchic spirit of the 1970s, Cutler says.

"John was a radical artist who was not limited by form or expectation," he says. "He was very much of his moment, but he broke new ground and was very much ahead of his time."