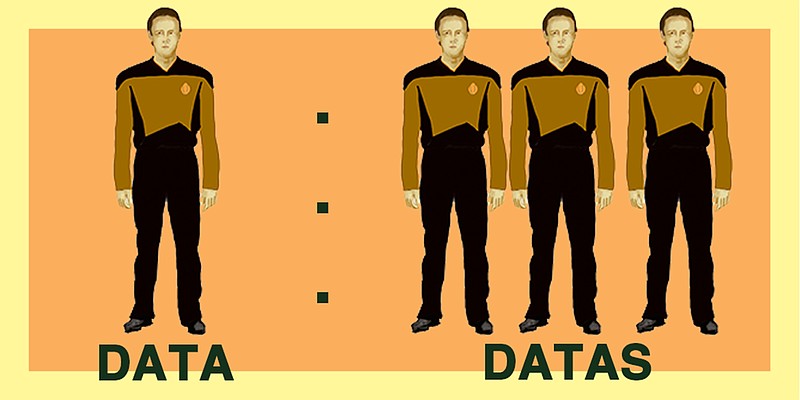

The word data leaves some of us in a conundrum.

Data is the plural of datum, the Latin word for something given.

Ordinarily, the plural word would get a plural verb.

The chickens are on their nests.

The cookies are cooling on the rack.

Books are my friends.

You'd think that a sentence should read:

The data are in on the patient's oxygen levels.

Roman statesman and scholar Cicero might have been appalled to hear what many people say today: "The data is sound." I mean, if his ears were still working after all these centuries.

Back in the 1960s, Theodore M. Bernstein in his "The Careful Writer" said data used in singular form is a solecism, or verbal blunder. He acknowledged that datum, the true singular form, wasn't used, even then.

But things have taken a turn, as things do.

https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=data

https://www.dailywritingtips.com/latin-plural-endings/

In common usage today, data is the same thing as information. The American Heritage Dictionary reports that, after surveying its Usage Panel members, by 2005 most accepted sentences using data with a singular verb. For that reason, the dictionary concluded that data in singular form is standard.

In 2013, Bill Walsh wrote in "Yes, I Could Care Less" that he sees data as a singular noun. Why? "Datum doesn't come up a whole heck of a lot in the real world."

The Associated Press still makes room for both forms of data. It says data typically takes a singular verb when one is "writing for a general audience."

But data takes a plural verb "in scientific and academic writing." (I suppose that's a "specific" audience?)

Other Latin plurals bring us other conundrums. (Conundra? No!)

Do you follow an agenda? My to-do list often serves as my agenda. Agenda takes a singular verb even though the true singular form is agendum. The American Heritage Dictionary says agenda has displaced agendum. And the plural is agendas.

The Latin plural for words ending in a traditionally add an e to the end.

So, one vertebra becomes many vertebrae. One larva might give you the willies. Many larvae might make you run fast and far.

Still, you're also likely to hear vertebras and larvas.

One antenna and two antennae? Or, is it antennas? Well, it depends. In zoology, it's antennae. The longhorn beetle, as the name implies, has extremely long antennae. But the metal things to improve radio and TV reception are antennas.

When words ending in ex are made plural, they go two routes: simple and a little complicated. More than one index is indexes or indices. But indexes is preferred.

It's the same with apex, or peak, which becomes apexes over apices. Apices looks strange to me and reminds me of the French word for spices, epices.

I'm going in circles over the plural of vortex, or whirlpool. The Associated Press and the American Heritage Dictionary prefer vortexes, but the rebellious Merriam-Webster editors prefer vortices.

English stays consistent with Latin words that end in is. I'm always surprised when I find this to be true.

analysis, analyses

axis, axes

crisis, crises

ellipsis, ellipses

parenthesis, parentheses

synopsis, synopses

thesis, theses

Appendix, which ends in ix, offers variety. An appendix is a small organ whose purpose is unclear, or it's supplemental information.

For the plural, the American Heritage Dictionary prefers appendices over appendixes. Merriam-Webster is the opposite. AP prefers appendices.

We have inconsistencies in how to make plural a word ending in o.

It's dingoes, but it's hippos.

It's potatoes, but it's ratios.

It's pistachios but torpedoes.

For stiletto, dictionaries prefer the plural stilettos over stilettoes. But both choices are listed.

How do we remember these differences? Lots of practice.

And now I can't get the Billy Joel song "Stiletto" out of my mind.

And we have the rare im used to make celestial plurals.

Cherub and seraph become cherubim and seraphim. But — did you guess it? — cherubs and seraphs are also acceptable.

Inconsistency pains me.

ASSOCIATED PRESS CHANGES

I was irritated with the AP Stylebook this past week. I didn't tell the editors.

When I was in grad school in the mid-1980s, I learned and have maintained ever since that one persuades someone to do something, but one convinces someone of something or that something is so.

This is what I mean:

With the proper amount of groveling, I could be persuaded to make a key lime pie.

With the proper amount of groveling, I could be convinced that making a key lime pie for you was essential.

With the proper amount of groveling, I could be convinced of the need for a key lime pie on the premises.

So, for more than 30 years, this has been ingrained in my brain. "The Careful Writer" promotes the distinction, too. Persuade is always followed by an infinitive, for example, "to make." Convince is followed by of or that.

In detail: "Convince has the meaning of to satisfy beyond doubt by argument or evidence appealing to the reason. Persuade has the meaning of to induce or win over by argument or entreaty appealing to the reason and feeling." OK, those two aren't all that distinct now that I hear it. But the point is, The AP dropped this distinction some time before 2015. I went looking for The AP rule, and it's nowhere to be found. AP has surreptitiously decided to omit the entry.

I will need a while to recover.

Sources include The Associated Press Stylebook, American Heritage Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Daily Writing Tips, "The Careful Writer" by Theodore M. Bernstein, "Yes, I Could Care Less" by Bill Walsh. Reach Bernadette at

bkwordmonger@gmail.com