It's funny how a few words can summon a voice from the dead. You're reading a passage or writing a sentence and something stops you: a flicker of the light, a shout in the distance. A white gap opens between your fingers and the page.

You silence your mind, strain to hear, but it's vague, a vague memory.

What did he say?

Last week, I was reading issues of the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat published between Oct. 9 and 19, 1920. I was trying to find just the right story for you, Dear Reader. As ever, your well being was my deepest concern, right behind my proximity to deadline, and I sensed you needed something uplifting or some merriment.

But the options were mostly crime. So much crime.

One of the crimes involved sordid campers from Oklahoma who had roved, with floozies, toward Hot Springs in search of businesses to knock over. They drove a sporty red car that did not belong to them. The Gazette published a muddy but usable photograph of one of the women. She said her name was "Ruby," but it wasn't.

Everything about that looked promising. But then they killed a policeman and shot off another's finger. Not uplifting.

Other criminals committed less disturbing crimes. A "daring" fellow robbed a Little Rock couple at gunpoint in their own driveway with neighbors 'round and about. The husband would have lost a diamond ring, but before he raised his hands overhead as directed, he slipped that ring from his finger and let it drop to the garage floor. The robber didn't notice.

But the item was short and didn't include an illustration. For supposedly good reasons (let's blame Edmund Arnold of Syracuse University, look him up), the public notion of what a proper newspaper looks like has changed since 1920, and so this column is supposed to come with a rectangle or two of "art" to break up the gray. The gray must be broken up, as though it were a robber baron's monopoly, and there must be "white space" between any unrelated items.

The gray! That is what we call my handcrafted, deadline-meeting sentences.

But back to 1920. Another wife and husband brawled over who was hogging the bedcovers. But they were Black citizens, and the reporter mocked them in dialect, a depressingly racist writing practice.

Also, speaking of racists, "nightriders" were riding about. And scammers were buying up bargain automobiles and burning them for the insurance. Fundraisers were fundraising for a Boys Club by pretending to auction off the boys. The head of the state Republican Party, A.C. Remmell, dropped campaign fliers out a window and was briefly detained for littering. A presidential election was underway, with calumnies flocking like grackles.

Peaches bloomed out of season in the Heights. In the Classifieds, someone was trying to trade $4,500 worth of shoes for a house. Also, the gas company wanted higher rates.

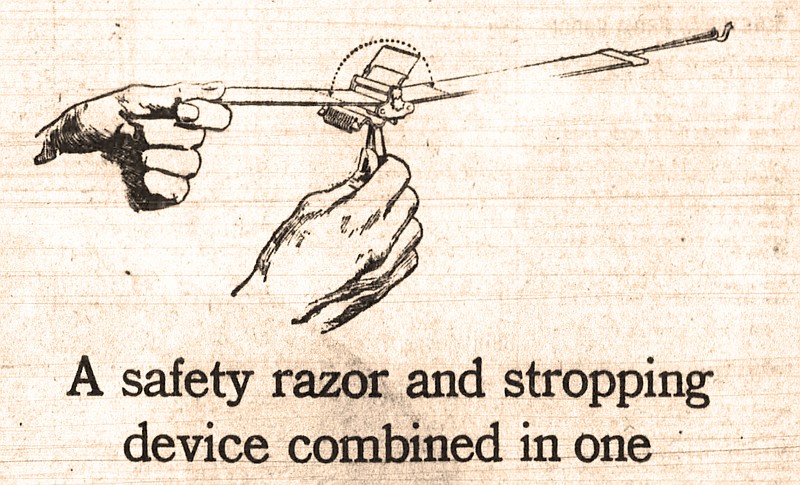

I was ready to settle on not-Ruby and an ad for a self-stropping safety razor when I noticed the burning cotton. In many tiny news items that week, and the next week and in the weeks that followed, cotton was on fire — burning up as seeds, as bolls, in fields, in train cars, inside cotton gins. The Ziba Bennett Plantation gin near Pine Bluff burned, a loss of $25,000.

I looked again at the headline references to night-riding and realized, "Oh." Those riders weren't only harassing Black people, they were burning and threatening to burn cotton. They were posting their threats on the doors of gins: "Stop production."

At England, three supposedly unidentified tenants of strangers stopped farmers enroute to a certain gin, warning them to turn back until the price of cotton improved. Signs appeared at that gin. Then a Black guard was shot to death in the night.

The Gazette reported that residents feared nightriders were to blame, but a grand jury rapidly indicted two Black men. One confessed to killing the guard for his money. The other swore he knew nothing. Their indictment "greatly relieved" the minds of England residents, the paper said.

At Bald Knob, eight white farmers were arrested and confessed to a widespread plot.

Although the violence appeared to be local outbursts by men described as "illiterate" and "not representative of the county," it came during a publicity campaign across the South intended to slow down the production of cotton, with ads placed in newspapers:

Don't sell a bale unless absolutely necessary. Borrow the money from your merchant or banker or warehouse receipts. ... Hold tight to your cotton.

Cotton had been much in demand during World War I. Prices hit 42 cents a pound in New Orleans. Farmers rushed to buy seeds and take lessons from Georgia farmers — in some cases, actual cotton-growing workshops — and planted their fields, ditch to doorstep, in cotton.

The largest cotton crop in history arrived on the market all at once in the fall of 1920.

So the market was ruinous. I ran across this phrase in some history of that time, and it stopped me in my tracks: "falling to less than 10 cents a pound by 1921."

I remembered. Maybe. Was it something my father had said to me?

Yes, decades ago, in our car, on the Memphis riverfront, near Beale Street.

"Right there," he had said, pointing to a concrete deck along a sooty warehouse. "I was standing next to my mother right there when she lost her land. They offered her 5 cents a pound. I told her not to sell and she did anyway. She lost her land, everything."

If that happened in 1920, he was 14 years old. But his father was alive in 1920. Wouldn't his father have gone to Memphis with her? Possibly Dad's father, a postmaster and merchant, was too busy running the store. Or maybe he didn't like her and didn't want to go. Dad didn't much like her.

His father died in 1922. If the Memphis deal happened in 1922, then Dad was 16 when his mother wouldn't listen to him on that concrete loading dock.

With no farm and a dead husband, how did she manage to support nine children?

And then I remembered that Dad was 16 the year he left home in Joiner for the merchant marine — using a false affidavit about his age that she swore out, to get him gone.

So, when did he tell me about that cotton deal? How old was I, 15? Why wasn't I paying better attention?

I do remember it now. And what I remember is his talking, talking, talking, talking, talking — a vast gray block of words, words, words.

He meant to give me a treasure, my family history.

Dear Reader, we might be living through a catastrophe on the order of that long-ago cotton crash. Someday, decades from now, you should tell the children all about your family's experience. But before you point your finger over those foolish young heads at an un-monument to everything and unburden yourself, notice: Are they listening?

If not, for heaven's sake, save them from self-blame. Break up the gray.

Email:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com