Documentary filmmakers sometimes find it useful to use dramatic re-creations to show events for which no actual footage exists. Because sometimes talking head testimony just doesn't cut it.

In films like "Actress," "Kate Plays Christine," "Bisbee '17" and now "Procession," Missouri-based filmmaker Robert Greene has used re-enactments -- or reimaginings -- to do more than fill in gaps.

"Of course in ("Bisbee '17") there's not footage because it's a hundred years after the deportation (in rural Arizona)," Greene says. "I don't think this film, 'Procession,' is about creating this footage where it doesn't exist otherwise. It think it's more about imagination and the psyche and going deep into someone using the creative process of making the scenes themselves to sort of investigate what the memories really mean. I think these films are interventions into reality in some ways."

For example, in "Kate Plays Christine," he and actor Kate Lyn Sheil explore what might have led Sarasota, Fla.-morning show host Christine Chubbuck to kill herself on the air in 1974.

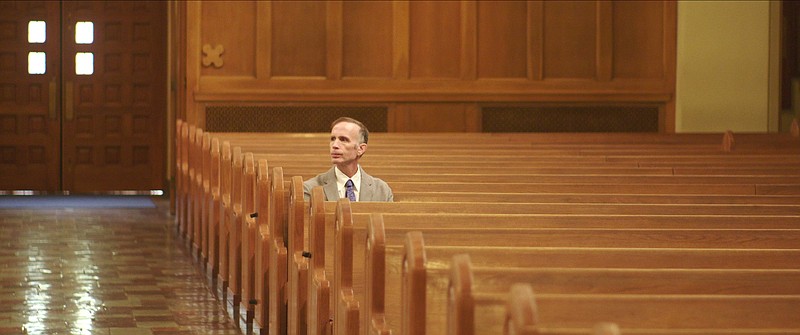

With "Procession," now streaming on Netflix, Greene works with Tom Viviano, Michael Sandridge, Dan Laurine, Mike Foreman, Joe Eldred and Ed Gavagan to dramatize how they experienced abuse from a Kansas City-based priest when they were children. Working with a young thespian named Terrick Trobough as a stand-in for their younger selves and drama therapist Monica Phinney, Greene and the survivors explore their memories and how they have struggled to recover from their experiences.

The segments include one priest with glowing green eyes that would seem at home in a horror movie and another where a survivor writes a letter to his younger self. The memories are harrowing (one survivor recalls going with his mother to deliver a cake to a priest who molested him). Another buries himself in The Who's mournful "Behind Blue Eyes" for hours.

"Mike loved the song for years," Greene says. "That song is about how you live with trauma every single day.

"The film is not about living in that sickening feeling. It's not about that at all. It's not even about what happened per se. It is about how you try to deal with what happened."

The process seems to help the now-middle-aged men regain their emotional footing. One ally in making the film was a bishop in Cheyenne, Wyo., who let the crew shoot at a site where one of the survivors was molested.

"Ed asked him," Greene says. "It wasn't like us being slick or smart. It was that this bishop [Steven R. Biegler] wants to help. He's one of the individuals in the church along this journey that simply wanted to be part of the solution instead of part of the problem. Finding those people who wanted to help us was really, really affirming for all of us," Greene says.

The reporters who comprised the Boston Globe's Spotlight Team and who were depicted in the Oscar-winning film all came from Catholic backgrounds, so they had an expertise in covering the abuse scandal other journalists might not have had. Greene, on the other hand, comes to the story from a different perspective. He's not a religious man.

"I have a Jewish grandmother who left Brooklyn and went to North Carolina," Greene says. "And then I have a Methodist grandmother who's very religious. I attended occasionally, and I'm fascinated by religion in a lot of ways. I'm fascinated with all the sort of narrative framework. So, I think the way to understand who we are is to understand the stories we tell ourselves, you know?"

One thing that separates "Procession" from previous movies like "Spotlight" is that it focuses primarily on the survivors instead of the people trying to expose the crime.

"Centering on survivors is totally necessary, but it's also difficult because there are few survivors who would put themselves out there in this way," he says. "These are men with lives. These are men with something to lose by sharing what happened, and they realized a.) they needed something, and b.) other people need to see what they can give. This is the one story that I would turn away from, that I couldn't pay attention to. I personally would be like, I can't handle this today, and then I realized I was contributing to the same silence that they have felt."

When he's not making films, Greene teaches at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, but his new film does more than simply recount what his subjects experienced. Seeing them gradually recover makes "Procession" oddly uplifting.

One way of showing the progress is by focusing on the men making the segments instead of simply presenting the short films. Seeing them react is more enlightening and involving than just having them recount their stories.

"What I'm interested in is that subliminal space between ideas," Greene says. "[Documentary pioneer and cameraman] Albert Maysles talked about how powerful it is to watch someone do nothing and just think. Filming someone in the in-between space between the staged thing and the so-called real thing, even though there's always a staged quality to everything that's on the camera. With just that little in-between space in this film, you really get a sense of the creative intent and the aftermath of the creative work."