"I have lost this battle because my force was too small. The Government must not & cannot hold me responsible for the result . . . . I have seen too many dead & wounded comrades to feel otherwise than that the Government has not sustained this army. If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army."

This was a shocking telegram, inasmuch as it was sent by General George B. McClellan to his superiors in Washington after the Seven Days Battles in 1862. Those who've served in uniform would be shocked more than others: First, a general officer--any officer--denying responsibility this way would be ostracized by all around him. But to chew out his boss--Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war--would be more than just getting close to the line of insubordination. It would be stomping on the line, kicking dirt on it, and crushing it under his boot.

According to the book "Tried by War" by James M. McPherson, the colonel who saw the telegraph deleted the last two sentences before sending it up the chain of command. Doubtless saving Gen. McClellan's job--for the time being.

We recommend "Tried by War" not because it's the best book about Abraham Lincoln. (That's reserved, for now, for "Team of Rivals" by Doris Kearns Goodwin.) But "Tried by War" brings you so close to President Lincoln's inner circle that you begin to get frustrated, too, just as he did, with the Union's efforts to keep the nation together: Why wouldn't the Union generals fight? And when they did fight, why were they so bad at it?

If the generals weren't using the army, Abraham Lincoln should like to borrow it for a while. But every time he gave orders to move, they balked. They always needed more men. They always were out-numbered by ghosts on the other side. They were always out-maneuvered. And not just George McClellan, but a string of other generals who came after him, with the same complaints. Until Lincoln found his Grant, it seemed the Union was destined to lose the War.

Because it didn't, we write this as citizens of the United States.

Gather around, children, and we'll tell you about a nation that really was divided to the core. So divided that half of it decided to make its own government. What we call red-state, blue-state was more like gray-state, blue-state. And the attacks on each other were more than rhetorical.

The nation needed somebody who could pull the strings, massage egos, calm Congress, walk through the landmines of fickle public opinion, issue legalese when needed, and hold forth in public messages of near Biblical elevations when that was needed in its turn.

The nation needed a president who could hold the pieces together, waging war when it was thrust upon him, urging malice toward none when the situation--or state, or congressman, or issue--changed. (He hoped to have God on his side, but he must have Kentucky!) The nation needed somebody who would not relent, but could compromise. The nation got Abraham Lincoln.

"Tried by War" tells of a mess of a man, standing over telegraph machines at all hours of the night, walking around in a deep depression, telling staff members of his darkest fears. He didn't want war, yet he oversaw the bloodiest one in American history. This wasn't the man in the movies, happily telling funny backwoods stories to make his points, as a preacher does to lead into his homily. Abraham Lincoln, for months, for years, watched his nation slip away from under him.

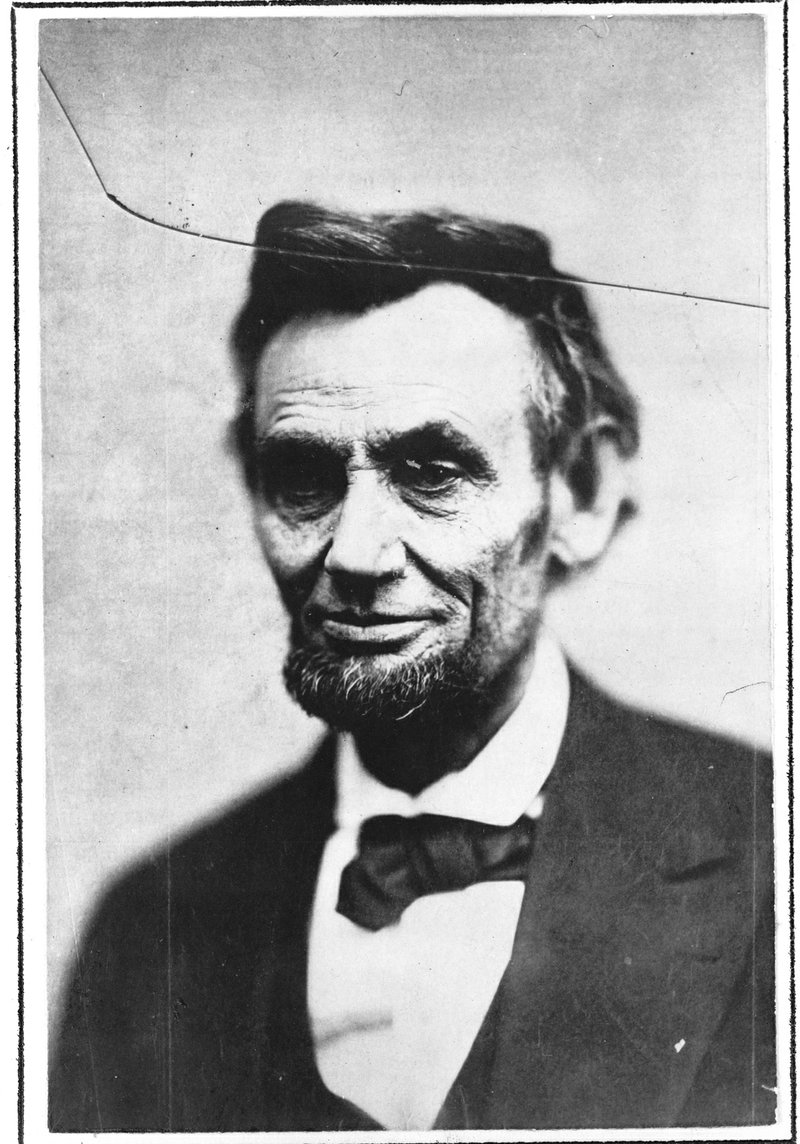

There is a famous photograph of Abraham Lincoln during this time. Somehow the photo was cracked. Which figures. The nation was divided, too, and nothing seemed to work to mend it.

The person most responsible for keeping this union of states together was a lawyer by trade. One with a deep hatred of slavery. But others also hated slavery, and would have destroyed anything to end it, including the Union. Abe Lincoln was no abolitionist in that sense. With him, ending slavery was a moral necessity, but so was preserving the Union. How could both be accomplished? Weren't the two ideas mutually exclusive?

They might have been with anybody else in the White House. Actually, they were with a Buchanan in the White House. And the War came . . . .

Abraham Lincoln once complained that he didn't live in the times of miracles. But he was mistaken. What else call it when the impossible happens? And the Union saved, and slavery ended, thank God almighty, free at last?

For once upon a time, the continuation of this nation was very much in doubt. The smart bet in 1861, 1862, 1863 would have been to put your money on two countries coming out of the American Civil War. Those who would tear the Union apart were winning. Or at least drawing things out enough to wear out the public in the North. But somehow, Abraham Lincoln was able to bring about a more perfect union. Something that we're still working on today.

THE MAN whose birthday we celebrate today wasn't always as popular as he is now. Even before he took office, half the country wouldn't have him. The U.S. representatives who mentioned him in debates--that is, those U.S. representatives who stayed in the Union--treated him with contempt. The papers would make modern editorialists blush. ("Filthy story-teller, despot, liar, thief, braggart, buffoon, usurper, monster, ignoramus Abe, old scoundrel, perjurer, swindler, tyrant, field-butcher, land-pirate."--Harper's Weekly magazine.)

But he held firm. And held the Union firm. With the firmness in the right that God gave him to see the right, and finished off the peculiar institution. And was shot dead for it.

Strangely, grievously, shamefully, some people today don't consider him an especially good person or president. And not just those unreconstructed Confederates who write books in their echo chambers suggesting the War wasn't about slavery but about economics and states rights. (The best way to end their arguments is to show them the declarations of each state as they left the Union one by one.)

But there are those on the left these days who'd take Abraham Lincoln's name off schools and buildings because he was a man of his time and his thoughts weren't as progressive as today's educated, or at least today's credentialed. We'd refer them to a good history teacher. But that's another editorial. Or several.

In the end, Abraham Lincoln would manage to win the most decisive battle of all, the one for public opinion. And he has managed to leap to the top of most lists of Great American Presidents. Some of us think that he should be there, at the top of such lists, and second place is only distant.

In great part because of Abraham Lincoln, this country is still one, under God, indivisible. And this editorial of Feb. 12, 2021, is being written in a free country, specifically in Little Rock, Ark., U.S.A.--not C.S.A.