There is a story, perhaps too deliciously ironic to be true, that holds that when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer chief Louis B. Mayer told Irving Thalberg he was planning on turning Margaret Mitchell's novel into a movie, Thalberg told his boss, "Forget it, Louie. No Civil War picture ever made a nickel."

The joke is that "Gone With the Wind" went on to win 10 Academy Awards and become the highest grossing film of all time (when adjusted for inflation). This was despite the fact it is nearly four hours long. And that in some ways, neither the movie nor the novel it is based upon is very good.

I say that in the spirit of provocation perhaps, but I also really mean it. I don't hate "Gone With the Wind," and I understand why some people love it. My mother loves it. And I think I can say why.

"Gone With the Wind" is a soap opera of such magnitude that it shames all objections. It is the biggest movie from back in the day when movies were big. Like all myths, it is a simple story rich in the old verities of honor, passion, courage and perseverance. As such it is bogus -- as well as ineffable and sublime. It is gaudy and silly and sad, overblown and overwrought and over-hyped. To resist it is to admit your cynicism, your proclivity to have no fun.

For whatever reason, "GWTW" was installed as an essential American myth, a cultural artifact that can hardly be avoided. While it might seem old-fashioned or quaint to modern audiences, it is a force with which we all must deal -- even if we deal with it by avoiding it or by adopting an attitude of smug condescension toward grandmother's all-time favorite movie.

We are farther removed from the date of the movie's premiere than that premiere was from the end of the Civil War. We can't see the film as those first audiences did. We know we're looking at what some people consider the greatest movie of all time and that knowledge forecloses our options. We either accept it and plunge headlong into its rich bittersweet pageantry or we hold it at arm's length like a curious purple bug.

I am one of those who hold it at arm's length. But I think it's a film everyone should see once because it has become part of our national collective consciousness, the communal storehouse from which we draw our freighted misconceptions of the way we were.

We should acknowledge that it is problematic, that it whitewashes the horrors of slavery by depicting life on the plantation as tranquil and the relationship between Scarlett O'Hara and her slaves as one of mutual affection. And we should acknowledge that even at the time the movie was released there were Black folks who objected to those characterizations. Producer David O. Selznick received letters from several groups complaining about the Mitchell's novel during pre-production, and in response he appointed two technical advisers -- both of whom were white -- to monitor "the entire treatment of the Negroes" portrayed onscreen.

'A WEAPON OF TERROR'

Even so the Los Angeles Sentinel, the Black-owned newspaper founded in 1933, was so disturbed by the movie that they called for a boycott of "every other Selznick, present and future." The Chicago Defender called the movie "a weapon of terror against Black America." There were protests held at its opening in Chicago, Brooklyn and Washington. The objections to "GWTW" are not a product of 21st-century political correctness.

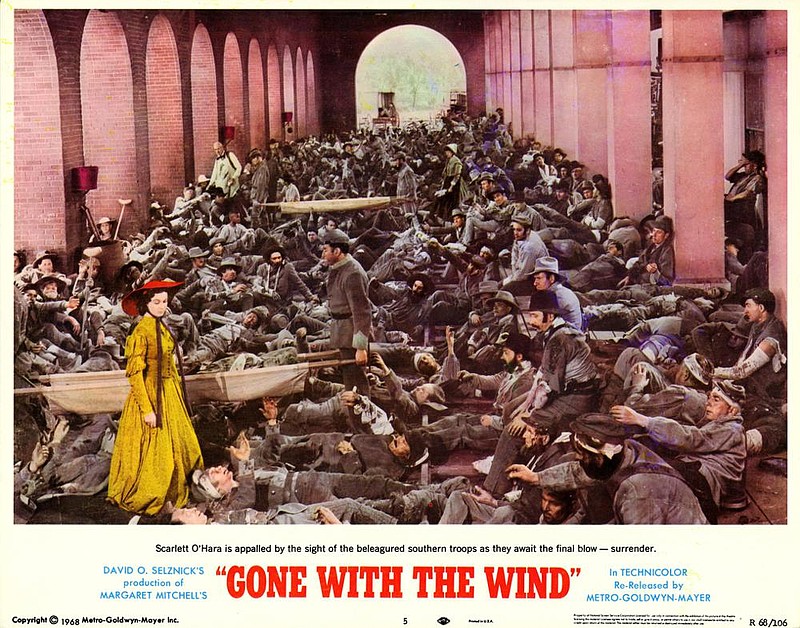

Leaving that aside, "GWTW" at the very least it is an overrated movie, highlighted by a few extraordinary scenes -- thousands of wounded soldiers, laid out row on row forever; a horse-drawn carriage silhouetted by consuming flames; some bloody, expressionistic skies. But most of the cinematography is pedestrian. Many scenes are ridiculously overlit -- no doubt because Technicolor was still a glorious new gimmick in 1939.

Vivien Leigh's performance as Scarlett O'Hara is iconic -- and unsubtle. She comes across as melodramatic, with an extraordinarily narrow range. She pouts well enough, but she seems as equally distressed over her Daddy's dying and Rhett Butler's leaving her as she does about her waistline.

Clark Gable often seems embarrassed to be appearing in the film. He was reluctant to play the role and he refused to read the novel when wife Carole Lombard (who had her eye on the Scarlett role) urged him to read it. At times he looks like a man bravely smiling through lower back pain as he delivers his lines as Rhett.

A DESERVED OSCAR

While Hattie McDaniel probably deserved her Best Supporting Actress Oscar and I think Butterfly McQueen strove to invest her comic performance with dignity (Malcolm X did not agree, famously recalling that "when Butterfly McQueen went into her act, I felt like crawling under the rug"), in general the level of acting in the movie is not high.

Victor Fleming is credited as the movie's director and he won an Academy Award for his contribution, but the film is hardly a tour de force. A certain stylistic inconsistency might be attributed to the fact that George Cukor, Sam Wood and William Cameron Menzies also directed several scenes without credit. Similarly, though Sidney Howard was the only writer aside from Mitchell to receive a writing credit, there were at least 10 other writers involved in scripting the movie, including Selznick, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. If "Gone With the Wind" is a masterpiece, then it is the rarest sort of masterpiece -- one made by a committee.

Yet I'd be fine with the movie's place in our cultural firmament had it not so warped our idea of what the Civil War was about. Along with D.W. Griffith's "Birth of a Nation," it installed in the national imagination a myth about the South that persists to this day.

COMPLICATED ISSUES

There was nothing romantic about the Confederate cause. The war between the states was fought over complicated economic issues, but those issues can be resolved into a simple moral question about whether a man should be able to exercise dominion over other men. In the end, the war was a contest over slavery and neither the pragmatism of Abraham Lincoln nor the raveling conditions of the first modern-fought war ought to obscure that.

To the film's credit there is nothing romantic in "GWTW"'s depictions of the horror of war as seen through the eyes of women. While Mitchell was a creature of her times and her stereotypical depictions of Black folk seem jarring to modern readers, her critique of the Southern aristocracy was acute. There is a kernel of social realism in the book, and moral ambiguity too.

Rhett Butler is no more standard-issue hero material than Scarlett is your average heroine; the virtue of Mitchell's alleged romance is that it doesn't romanticize these lovers. It doesn't gloss over their flaws or offer the kind of happily ever-after remedy that Hollywood has come to insist upon. Rhett and Scarlett are in love, but they are also who they are. They are doomed by their own character.

Mitchell's novel is not great literature, but at least it aspires to be. She was trying to be an American Dostoevsky. She wasn't, though some people think she came closer than people like me are willing to credit.

Perhaps writing the best-selling (and no doubt best-read) American novel of all time provided her some consolation.

More News

‘Gone With the Wind’ (1939)

Cast: Vivien Leigh, Clark Gable, Olivia de Havilland, Leslie Howard, Hattie McDaniel, Butterfly McQueen, Oscar Polk, Victor Jory

Director: Victor Fleming

Rated: Not rated

Running time: 3 hours, 58 minutes

“Gone With the Wind” is screening in Little Rock on Jan. 12. For more information see riverdale10.com.