I cross DeRoche Creek and enter Clark County on my trip from Benton to Texarkana on U.S. 67. Clark County was one of the original five counties in the Arkansas Territory.

"Clark County included all or parts of at least 15 counties in present-day Arkansas and parts of six counties in what's now Oklahoma," writes Wendy Richter, the former director of the Arkansas State Archives. "The county was named for the Missouri territorial governor William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Clark County is part of two of Arkansas' natural regions--the Ouachita Mountains and the Gulf Coastal Plain. Its physical characteristics made the area ideal for farming and hunting.

"Before Europeans arrived, Native Americans, particularly the Caddo, inhabited the land containing heavy forests, abundant game, rich soil, clear streams and salt. Archaeological evidence attests to the lengthy presence of the Indians in the area. In the 16th century, Hernando de Soto was the first European known to explore the Ouachita Mountain region. He was followed more than a century later by the French, who named many of the county's topological features. By the 1700s, Indians had largely vacated the area as the Europeans continued to explore and occupy it."

Prior to entering the county seat of Arkadelphia, I pass through Caddo Valley, home of numerous restaurants and motels that were built during the past 50 years to serve travelers on Interstate 30. In 1968, the Arkansas Children's Colony--now the Arkadelphia Human Development Center--opened at Caddo Valley.

"Never numbering more than a few hundred in population, the area wasn't formally organized into a city until 1974," writes historian David Sesser of Henderson State University. "Incorporation was quickly followed by a city hall and creation of a police department and fire department. This move was brought on by Interstate 30, with an exit placed in Caddo Valley. The interstate led to a boom in the construction of gas stations, motels and restaurants.

"The slow growth exhibited during the previous century was replaced with a much faster rate of expansion, in both the economy and population. The city grew into a place for travelers to stop between Little Rock and Texarkana. It also served visitors to DeGray Lake. Thousands of visitors to the lake each year pump money into the Caddo Valley economy."

Leaving Caddo Valley, I cross the Caddo River. It's among the most beautiful streams in a state filled with scenic rivers and creeks. The area from the bridge at Caddo Valley to where the stream empties into the Ouachita River is popular with floaters. I'm a few miles downstream from DeGray Dam at this point, and make my way into the old river town of Arkadelphia, my hometown.

In 1809, just six years after the Louisiana Purchase, William Blakely established a blacksmith shop on the west bank of the Ouachita River at a place called Blakelytown. That later would become Arkadelphia. On the other side of the Ouachita River, John Hemphill began a salt mining operation. It was considered to be among Arkansas' earliest industries.

Despite the accomplishments of Blakely and Hemphill, Jacob Barkman is known as the Father of Clark County. Barkman opened river traffic from Arkadelphia all the way to New Orleans, first by pirogue and later by keelboat. In 1830, he initiated steamboat transportation on the Ouachita.

"Barkman's home served as the site of the first county court, the first post office, a stagecoach stop, a racetrack and an ill-fated textile mill," Richter writes. "Blakelytown's first general store opened in 1817, operated by J.S.T. Callaway. Johnathan O. Callaway is credited with having built the town's first hotel in 1843. Shortly thereafter, the Spence Hotel was constructed and became a well-known stopping place in the region.

"Moses Collins arrived in the county in 1830 and built a sawmill and gristmill on Terre Noir Creek. A brickyard was established the same year. Reflecting the emphasis on the region's natural resources, agriculture dominated antebellum Clark County's economy. As in much of Arkansas, cotton's importance grew during the antebellum period, and slavery was common throughout the county. In the 1830s, the Military Road was constructed along the Southwest Trail through Clark County and passed near Barkman's home."

U.S. 67 and Interstate 30 now cross the Caddo River within a few hundred yards of where Barkman lived. His home was adjacent to a Caddo burial mound. Horses raced around the mound and drew large crowds.

Five miles from Arkadelphia, I pass through Gum Springs, a community that had a population of 120 people in the 2010 census.

"Gum Springs is thought to have received its name due to a spring located near a gum tree," Jacob Worthan writes for the Central Arkansas Library System's Encyclopedia of Arkansas. "In the mid-20th century, the town rose from a farming community to become an industrial center in Clark County. Today, Gum Springs has dwindled to a small rural community, as have neighboring towns.

"Little is known about the origins of the town other than the fact that the Clark County poor farm was established near the eventual site in 1887, and a post office was established in February 1889 under the direction of postmaster Henry Gerrell. In the early 1900s, the town--which was established along the railroad line--was primarily an agricultural community composed of farmers and sharecroppers."

That changed in the 1950s with the establishment of Reynolds Metals Co.'s Patterson Plant. Aluminum production began in February 1954 and continued until June 1984. Clark County built an industrial park at Gum Springs in 1979.

For several years, area residents awaited construction of a giant Chinese-owned pulp mill that was to have been the most expensive industrial project (at a cost of $1.8 billion) in state history. With the recent breakdown of U.S.-Chinese relations, though, plans for the mill, to be built by a company known as Sun Bio, were abandoned.

In the Gum Springs area, one can still see stretches of pavement from the highway that was constructed in the 1920s. It's also possible to spot the remains of tourist courts and other businesses that were in operation when this was the main route to Texas.

The next community is Curtis, established as a refueling stop along the railroad line. In the 1870s, railroad officials distributed promotional brochures encouraging people to settle there. By 1880, a depot had been established at Curtis. A number of Welsh families moved to the area in 1881. Swedish families also moved there.

Leaving Curtis, I cross Terre Noire Creek and make my way into Gurdon. The town appears to have been named for Gurdon Cunningham, who surveyed the right of way for the railroad in this part of Arkansas. Gurdon later became an important center of both the rail and timber industries.

"The number of mills operating in the area reached a peak of 10 in the late 19th century," Sesser writes. "The combination of people passing through town on the railroad and the rough nature of the timber business brought unsavory characters to Gurdon. When the first minister arrived in 1881, he found a community of 500 people with three saloons and no churches. The situation changed by 1887 when all saloons were banned."

I exit Gurdon and continue toward the southwest on U.S. 67, soon finding myself in the Little Missouri River bottoms. The river begins in the Ouachita Mountains of Polk County and flows to the southeast through Montgomery and Pike counties. Narrows Dam on the river was constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The dam, which forms Lake Greeson, was authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1941 and completed in 1950 about six miles from Murfreesboro.

Below the dam, the river exits the Ouachita Mountain foothills and enters the Gulf Coastal Plain. I cross the Little Missouri a bit to the west of where it empties into Ouachita River and enter Nevada County, formed by the Legislature in 1871 from parts of Hempstead, Ouachita and Columbia counties.

The population of Nevada County grew from 12,959 in the 1880 census to 21,934 in the 1920 census. It has been falling ever since. There were 8,997 Nevada County residents in the 2010 census.

Meanwhile, the population of the county seat of Prescott more than tripled from 1,287 in the 1890 census to 3,960 in the 1950 census as the town became the center of timber operations in this part of southwest Arkansas. The city's population is now estimated at 3,000. It's the same story as that of most towns in the south half of the state: population loss.

Continuing toward the southwest on U.S. 67, I cross Terre Rouge Creek and pass through Emmet, which had 518 residents in the 2010 census. Emmet was established as a railroad stop along the Cairo & Fulton line. A post office opened here in 1871.

In 1959, Arkansas Louisiana Gas Co. opened Arkla Village as a tourist attraction along the highway. It was a pet project for Arkla boss Witt Stephens.

"It featured a saloon and general store, a livery stable and a museum," writes Steve Teske of Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. "Connected with the village was a factory that built horse-drawn carriages. Employing 34 workers, the factory included Amish farmers and Hollywood movie makers among its customers. Both the village and the factory had closed by 1970."

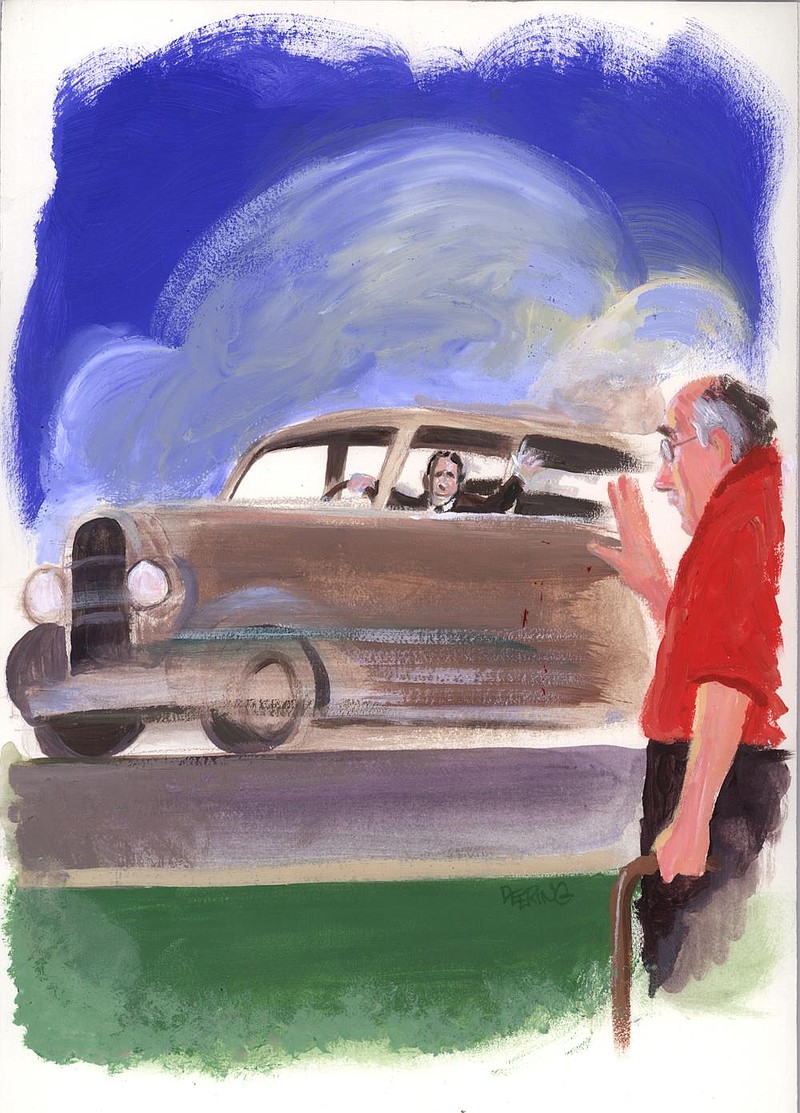

Construction of Interstate 30, which caused all but local traffic to abandon U.S. 67, spelled doom for attractions such as Arkla Village.

I will always remember where I was in 1980 when the United States defeated the Soviet Union in hockey (in the game known as the Miracle on Ice) during the Winter Olympics. Okolona High School had a basketball sensation named Ricky Norton, and I was calling all of Okolona's post-season games for KVRC-AM in Arkadelphia. I was at a district tournament game in the old Emmet gymnasium that day.

L.D. Hoover, working back in the studio, interrupted me and said: "Rex, there has probably never been a hockey score given on KVRC. But you might be interested to know that the U.S. just beat the Russians."

Entering Hempstead County, I pass through Perrytown, which had 272 residents in the 2010 census. Named for businessman Perry Campbell, Perrytown was incorporated in 1963. Campbell established a truck stop next to the highway in 1955. During the next several years, he added a restaurant and Perry's Congress Motel.

Residents decided to name the community Perrytown against Campbell's wishes. An October 1963 story by Wick Temple in the Arkansas Gazette was headlined "New State Municipality Spawned by Thriving Truck Stop and a Dream."

Campbell served as mayor. He died in 2005 and was honored in a speech on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives by then-U.S. Representative Mike Ross from Prescott.

I'm in Hempstead County now. It was established in December 1818 before Arkansas became a territory. It's time to head to the county seat of Hope, a place known for producing business and political leaders such as Bill Clinton, Mack McLarty and Mike Huckabee. And, of course, watermelons.

"The town developed as the Cario & Fulton tracks were being laid from Argenta (now North Little Rock) to Fulton," the late Mary Nell Turner, a noted Hope educator and historian, once wrote. "The first passenger train pulled into what was known as Hope Station on Feb. 1, 1872.

"By the time the railroad offered lots for sale, the wood-frame depot was almost complete. James Loughborough, the railroad company's land commissioner, named the workmen's camp in honor of his daughter, Hope."