WASHINGTON -- Abraham Lincoln rose from his chair and walked to the speaker's table on the East Portico of the Capitol. He pulled his cut-and-paste address from the breast pocket of his coat, and slowly put on his metal-rimmed glasses.

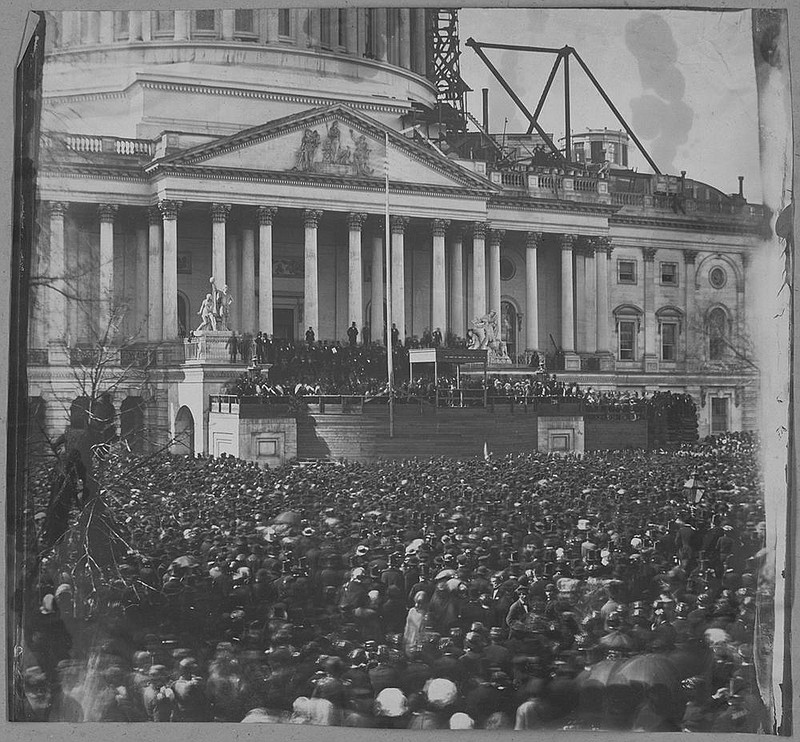

As he stood bareheaded, a throng of 30,000 people spread before him -- the largest inauguration crowd the city had ever seen, and one that included many African-Americans, who were legally banned from the grounds unless on "menial" duty.

But below the platform, the Army had deployed artillery. Snipers watched from rooftops and windows, and Lincoln had been guarded by infantry and cavalry on his carriage ride through the streets to the Capitol.

Many people wanted him dead.

"There goes that Illinois ape, the cursed Abolitionist," a woman in crowd was heard to say. "But he will never come back alive."

As a tense Washington approaches President-elect Joe Biden's inauguration Wednesday amid apocalyptic right-wing threats and a full military lockdown, historians say it was Lincoln's first inaugural that was really the most hazardous in the life of the country.

"By far," said Lincoln historian Harold Holzer.

Since his election in November 1860, there had been endless reports of plots to kidnap or kill him, or to march on Washington and seize the government, according to accounts by Holzer and fellow historian Ted Widmer.

One alleged plot called for the seizure of the city and the public archives, and for the insurrectionists to be acknowledged abroad as "The United States of America."

"Government of the people hung by a slender thread," Widmer wrote.

As for Lincoln, someone had planted a bomb on one of his railroad cars. He had been offered a pistol and a knife for his protection. (He declined.) And he had to be sneaked to Washington through hostile Baltimore as the "package" on a secret train under the code name "Nuts."

The country was seething over the issue of enslavement, which Lincoln and many in the North would seek to end, and which most in the South vowed to maintain at all costs.

Seven states had already seceded from the Union to set up an "alternate" government, as Holzer put it in an interview.

And there were those who believed that his inauguration on the steps of the Capitol would be the perfect theater for assassination, Widmer wrote in his new book, "Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington."

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, sat behind Lincoln during the event, "expecting to hear ... the crack of a rifle" at any moment.

But "his hour had not yet come," Greeley recalled. The tragedy would not play out for four more years.

The Army officer in charge of security, the aging Gen. Winfield Scott, called it "the most critical and hazardous event with which I have ever been connected."

Scott, who was 74, had received death threats himself, according to the website abrahamlincolnonline.

But he stood 6-foot-5, had been in the Army for 50 years, and said of his artillery:

"If any of the Maryland or Virginia gentlemen who have become so threatening and troublesome show their heads or even venture to raise a finger, I shall blow them to hell."

The ceremony on March 4, 1861, took place at the same East Portico where part of the right-wing mob incited by President Donald Trump stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 and terrorized members of Congress.

The mob stampeded up the main steps there and celebrated beneath the 9-foot-tall marble figures of "America," "Justice" and "Hope" in the architectural pediment over the central entrance entitled "Genius of America."

The figures are reproductions of the originals, which stood there when Lincoln spoke.

And while the Jan. 6 rioters threatened current legislators with death, it was Lincoln who in 1861 "had engendered more hatred than anyone in American history," Widmer wrote.

That hatred would boil over only six weeks later in the Civil War, and eventually claim the lives of Lincoln and about 750,000 Americans, about 2.4% of the population of 31 million at the time.

That percentage of today's population of 328 million would equal the deaths of about 7 million people.

As he adjusted his glasses that Monday 160 years ago, he had just completed a 13-day, multicity, 1,900-mile train journey from his home in Springfield, Ill., where he had told well-wishers he didn't know when, or if, "I may return."

Even before he left, word came that assassins awaited him in Baltimore, a city known as "mob town" for its violent street gangs, and a place where 30 people had been killed on Election Day four years earlier.

Lincoln's security people later learned alleged details of a plot by assassins to jump him there, create a diversion and kill him.

But that was near the end of the journey. Some in his circle thought the trouble would happen earlier, on Feb. 13, while he was in Cincinnati, the day presidential electoral votes were counted in the Capitol back in Washington.

"Ever since Lincoln's victory in November, rumors had ricocheted around Washington that the recount offered the South a chance to turn back the election," Widmer wrote.

"Through parliamentary maneuver, or sleight of hand, it might be possible to declare a miscount and throw Lincoln's election back into the cloakrooms," he wrote. "There a more acceptable result could be found."

Just before his train left Cincinnati, an unattended carpetbag was found in Lincoln's car.

Inside was a time bomb set to explode in 15 minutes, Widmer wrote. By one account, it could have destroyed the car and everyone in it.

From Cincinnati the train went on to, among many other places, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Buffalo, Albany, N.Y., Philadelphia and Harrisburg, Pa. Huge festive crowds and VIPs greeted him along the way with cheers, bands and fireworks.

But then came Baltimore, the last stop before Washington.

Because of the danger, Lincoln's approach to Baltimore was secretly changed, according to Widmer.

The original plan was for Lincoln to arrive from Harrisburg at the Calvert Street station, Widmer said. But detectives learned that supposed assassins planned to ambush him as he got off the train there.

So Lincoln was instead spirited from Harrisburg back to Philadelphia. And in the middle of the night was placed incognito on a routine passenger train that arrived at Baltimore's President Street station, Widmer wrote.

But that presented another problem. Because of restrictions on locomotives in the city, the cars at President Street had to be pulled by horses many blocks around the Inner Harbor to the Camden Street Station.

There they were attached to locomotives that took them south to Washington. But that slow horse-drawn trip would be the danger point.

After the official stop in Harrisburg on Feb. 22, Lincoln changed some of his clothes. He put on a soft wool cap and an old coat, seeking to camouflage his lanky 6-foot-4 frame. He thought it worked. "I was not the same man," he said.

He got into a carriage with aides and hurried to the depot. He boarded a small train, with its lights out, and headed for Philadelphia, 100 miles east. All other trains had been diverted. A detective telegraphed ahead: "Nuts left at six."

"The package" reached Philadelphia at 10:03 p.m., and just before midnight he was sneaked onto a private sleeping car aboard the last train south.

At 3:30 a.m. it reached Baltimore. The locomotive was uncoupled and horses hitched.

"The streets were deathly quiet as the horses pulled Lincoln's car, hearse-like, through the dark streets," Widmer wrote. But the transfer was uneventful. The southbound train left at 4 a.m. and arrived in Washington two hours later.

But as he got off the train, a mysterious-looking man watched from behind a pillar. As Lincoln passed, still semi-disguised, the man reached out and grabbed him by the shoulder. "Abe, you can't play that on me," he said.

A Lincoln aide, the detective Allan Pinkerton, elbowed the man and got ready to slug him.

But Lincoln grabbed Pinkerton's arm. "Don't strike him, Allan, don't strike him!" Lincoln cried out. "That is my friend Washburne -- don't you know him?"

It was Elihu B. Washburne, a congressman from Illinois and a longtime friend and ally who was worried about Lincoln's safety and had gone to meet him at the station.

No one else took note of them.

Nine days later, Lincoln stood before the crowd to be inaugurated.

"Fellow-Citizens of the United States," he began, stressing the word "united."

"A disruption of the Federal Union, heretofore only menaced, is now formidably attempted," he said. "I hold that ... the Union of these States is perpetual."

"In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war," he said. "You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to 'preserve, protect, and defend it.'"

"We must not be enemies," he said.

"Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."