JONESBORO -- Dr. John Thompson, a pulmonologist at St. Bernards Medical Center, arrives at work at the hospital's intensive care unit around 7 a.m.

He reads charts, talks to the medical team and tries to get a feel for who needs his immediate attention.

"Then I kind of just dig in and I wait for the bomb to go off in the middle of my day," Johnson said in an interview Wednesday. "And it always goes off."

As a medical doctor who treats disorders and illnesses of the respiratory system, Thompson has seen his patient load more than double since covid-19 officially hit the state in March.

The virus has infected more than 270,000 people in Arkansas. Many of them have no or mild symptoms, but some suffer severe problems.

In some of the worst cases, the highly contagious virus largely attacks the lungs, making it difficult and sometimes impossible for its victims to breathe on their own.

"You went from 30 sick patients every day to about 60 really sick patients," Thompson said. "Our covid-19 patients, especially the ones that get really sick, just require so much time and are here for so much longer."

[CORONAVIRUS: Click here for our complete coverage » arkansasonline.com/coronavirus]

And they die in greater numbers -- now often dozens a day, with a state death toll of more than 4,300.

"It's just a constant give and take all day long. So many people, despite what we have to treat this horrible disease, they just ... ," Thompson's voice cracked and trailed off.

He looked down at his feet, sucked in a breath, then whispered:

"They just die."

What makes it even harder to grasp, Thompson said, is that there is no rhyme or reason to who dies and who survives.

Before covid, the majority of ICU patients were sick with a predictable illness or injury.

"They have heart disease. They're old, obese, sick," Thompson said. "But now there are plenty of people that don't fall into that category that are here. Now, it's hard to explain to people why a 45- or 50-year-old that's otherwise healthy -- it's hard to tell their family that they're not doing well and probably aren't going to make it out of there."

Thompson has been a doctor for 20 years.

"A day here and a day there, yes, I've had horrible days where horrible things have happened. I've shed tears before," Thompson said, his eyes brimming.

He paused, opened his mouth to speak, but no words came out.

Thompson steeled himself.

"But I have never felt like this for this long," he said. "I think there's going to be a lot of scarring."

FINDING BEDS

In December 2019 -- just a few months before the state's first confirmed case -- St. Bernards sealed off the doors to its old ICU unit and opened its new 245,000-square-foot tower as the hub of all surgical and intensive care services.

The new tower took years of planning and construction to bring to fruition.

But the pandemic has forced the hospital to react much more quickly. Staff carve out space, often on a moment's notice, to create more bed space. They've reopened doors they once thought were shut forever.

"It was so surreal," Thompson said. "The doors were closed off and you couldn't get in there. Then they opened the doors again to the old ICU. To walk back into this place you never thought you'd ever see again, it was very surreal."

The hospital, a Craighead County staple for more than 120 years, has about 440 total beds.

Pre-pandemic, St. Bernards had at most 80% of its beds in active use.

"We routinely see it above 90%, often higher than 95%," said Mitchell Nail, hospital spokesman. "Finding available beds -- both in ICU and regular beds -- has been a challenge, as has finding enough staff who can care for those patients."

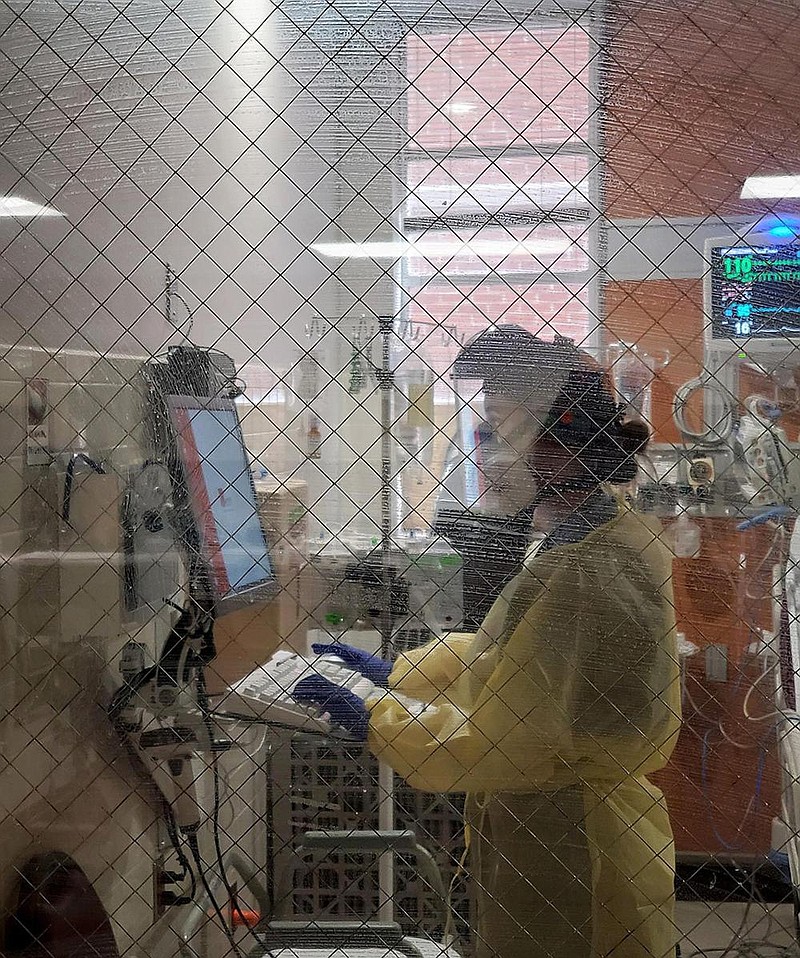

St. Bernards allowed the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette to interview its employees to give readers an idea of the toll of the pandemic on health care systems and employees.

In December 2019, Emily McGee, the hospital's ICU nursing director, trained new staff for the tower's expansion from a 32-bed ICU to 46 beds.

On Friday, the ICU expanded to 79 beds.

"We had about 110 nurses then and now we have about 150," McGee said. "In addition to nurses working additional shifts, we've had nurses from throughout the hospital come train in the ICU so they can help. We've had physician nurses that have stepped up and trained. We've had travel nurses that have come in to assist us. We're constantly looking at creative ways to recruit nurses to help."

St. Bernards Hospital Administrator Michael Givens said the hospital began drafting a covid-19 battle plan when the first case hit U.S. shores in early February 2020.

"In March 2020, we admitted our first person thought to have the virus, and we have cared for patients with it since then," Givens said. "As a team, we knew this virus was going to be serious and devastating. I don't think anyone initially thought it would be this devastating or continue for this long."

As the pandemic progressed, a key challenge became creating enough space for all patients in the northeast region of the state, Givens said.

"We must stay ahead in creating new capacity and ensuring that we access any new treatments that can help reduce the virus's impacts," Givens said. "While our team has responded well to these challenges, the pandemic has continued in our region for nearly 11 months. That's a marathon, not a sprint, and we must continue to encourage and provide their needed support."

'TAKING ITS TOLL'

McGee started at St. Bernards nearly two decades ago as a patient-care technician in the ICU while she was in nursing school.

She loved the talented, compassionate nurses she worked with and the happy, hopeful, family-like atmosphere.

"Before covid, it was smiling coming into work, the excitement of the new tower. It was healing patients and having our patients come back in and thank us for what we did," McGee said.

She paused and swallowed hard.

"Now, we're coming in -- not in dread -- but with sorrow for the patient population that we're caring for now, for the possible outcomes that they could face," McGee said. "It's not the happy environment that you used to see."

McGee's work hours grew from about 40 on average to at least 50 per week.

ICU nurses went from working about 36 hours a week to about 48 to 60 hours, McGee said.

"I'm nothing compared to them," McGee said. "All the bedside nurses, the aides, everybody have truly stepped up and gone above and beyond. They were asked to sign up for on-call shifts. They did it without batting an eye."

Even with the extra nursing staff, it's a constant stretch to cover the sheer volume of patients.

"We've gotten creative. We still maintain our 1:2 nursing ratio. However, we have developed a team nursing model. It's one ICU nurse to three ICU patients. Between six ICU patients, we have a non-ICU RN or LPN that assists those nurses."

The nurse's station is now covered with iPads and cellphones that are carried to the patients so they can talk to their loved ones every now and then.

"Before you were able to sit and visit with the families. Nurses pride themselves on their relationships with families. It's a huge part of our job," McGee said. "Covid has taken a huge part of that away. That's one part that they could enjoy and look forward to. Not getting to experience that any more is taking its toll."

'NOT ENOUGH TIME'

Treating patients in the ICU now takes up the bulk of Thompson's work load.

The pulmonologist easily spends 13 hours a day for seven days caring for his patients.

The starkest time of a covid patient's battle comes when the patient can no longer breathe unassisted and requires a machine's help.

Thompson faces the patient and delivers the grim truth.

"I tell them that I'm going to do my best and that I'm going to give them everything that I can give them," Thompson said. "But at the end of the day, if you get put on a ventilator, there's probably a better than 50/50 chance that you're not coming off. I tell them that.

"I tell them that I'm going to give you some medicine to sedate you and I'm going to put the tube in your throat. And then I'm going to try to keep you comfortable and hope that your body heals over time."

Thompson does this while wearing protective gear that resembles a spacesuit and in a noisy negative-pressure room that sounds like a tornado coming.

"I have to tell them the truth, which is they may never come off," he said.

Thompson intubated a friend's father a few weeks ago.

"He knew he wasn't coming off the ventilator and I ... and I knew, and, uh, then it just ... uh ... ."

Thompson lurched forward in his chair, bent his head and clasped his hands in front of him. He rocked back and forth.

"Those are the hard ones. When they look you in the eye and they know what's happening and they know that this is probably it," Thompson said. "But not today, in a few weeks. However long it takes them to decompensate over time."

Covid patients are heavily sedated -- "but not too sedated" -- before going on the vent and they're prone on their abdomen, which complicates patient care, Thompson said.

Covid robbed him of time to talk to patients' families.

"I talk to as many as I can. Two years ago, if somebody was that sick in the ICU, your family members would be sitting there and we would be talking multiple times through the day about what's happening," Thompson said. "If we had 40 beds, maybe four or five people were that sick. Now, I've got 60 beds and 40 people are that sick.

"I like to talk to families. That's part of my job. And I like to talk to patients. But, in there, I can't communicate with them very well. They can't hear me. I can't hear them," Thompson said. "I want to talk to families. I want to do all of these things. There is not enough time."

A MILD CASE

In October, Thompson was diagnosed with covid-19.

"My wife has this obnoxiously strong soap. Every time I walk into the shower, it just knocks me over," Thompson said. "Then one day I walked into the shower and I could smell it, but it didn't overwhelm me."

His symptoms were mild.

"I never felt like I needed to go to the hospital, but I felt rotten for about 10 days," Thompson said. "The fatigue was the worst thing. I slept for 16 hours a day and I could've slept all 24."

He was struck by his emotional response of lying there alone, quarantined from his wife and kids.

"It's just not good for your mental health. I was just thinking, 'I'm here in my house. I've got my iPad. I've watched everything Netflix has to offer,'" Thompson said. "I couldn't help but think about people that were here and on a ventilator. Why was I blessed just to have a simple illness for a week? I had guilt that I wasn't sicker from it."

His own illness emphasized the randomness of the virus, he said.

"Did it give me any great insight on what it's like to be truly sick? No, because I wasn't," he said. "I thank God every day that I wasn't."

According to Arkansas Department of Health data, health care workers make up about 7.2% of covid-19 cases.

NO ONE DIES ALONE

At the beginning of the pandemic in the state, no one outside of the health care team was allowed on a covid unit. Many virus victims died alone, without their families.

"Now, if we see that a patient is not going to survive, we bring families in to see them," McGee said. "We feel it's very important to have that closure and be able to say your goodbyes."

If there is time, Thompson tries to get the families in to see the patient before the ventilator is placed.

"I just sit outside the room and see them in there while I'm doing 10,000 other things and I think, 'This may be the last conversation that person has with their loved one.' This is one of those things I try not to think about," Thompson said. But he added that sometimes there's no time to bring in the family. "It's an emergency situation and it has to happen right then and then that [family visit] doesn't get to happen."

Early on, St. Bernards began its "No One Dies Alone" program. Hospital employees -- regardless of position -- volunteered to undergo training to sit with patients as they pass away.

"Not all patients have families that are able to come up here. That has been a wonderful resource," McGee said. "And it's not just a resource for our covid area, but throughout our facility."

The hospital's pastoral care also sits with patients, reads Scriptures, sings hymns and talks to patients to ease their passing. The pastors visit ICU patients daily and have close relationships with families.

Unlike before the pandemic, deaths are now constant, McGee said.

"You would think with repetitious behavior, you'd become accustomed to it," she said. "But it's not something you can become accustomed to."

STRESSFUL IMPACT

Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome is the reality for health care workers now, McGee said.

"Everybody sees people at home sick with covid and it seems like they had a simple cold," McGee said. "You don't see the severity of what covid is. You don't see the families saying goodbye to their loved ones because covid wreaked such havoc on their lungs. You don't see the heartbreak of a patient stuck in a room by themselves, not being able to talk to anybody but the health care team because of covid.

"Covid has completely changed our world. It has completely changed nursing as a whole. I wish everybody could just shadow us at work one day, just to see the true impact that covid has had."

Dr. Eudy Bosley, a psychiatrist with St. Bernards Behavioral Health, compared the pressure and emotional toll on health care workers to that of first responders to the 9/11 attacks.

"Health care workers are doing it constantly, working and suffering day after day, for 10 months now," Bosley said. "Imagine being in that constant state of seeing people suffer. With that kind of traumatic exposure, people can develop the same trauma-related symptoms that come from the battle field in war zones."

St. Bernards continually implements new measures to help employees cope.

The hospital offers Employee Assistance Program free virtual counseling and support groups via Zoom. Employees are encouraged to take time off.

"As important as our work is, employees need time with their families without work distractions," Nail, the hospital's spokesman said. "We encourage them to recharge whenever possible."

The hospital's morale efforts include a therapy dog making rounds, T-shirt day and locally brewed coffee service.

"Despite how much the virus has impacted each of us, hope always abounds," Nail said. "We look forward to the day when nobody in our hospital has covid-19 -- and it will happen -- but we also can't neglect the joys we experience every day: The covid patients who recover; the cancer patients who 'ring the bell' to celebrate their last treatments; or the young couples with their first newborns. These are the reasons why we're here and why we'll continue to be here."

Thompson said what touches him the most are the housekeepers, cafeteria workers and other support staff who didn't choose medical care as their life calling, but face the same dangers and hardships.

"There are people in this institution, and that are in similar institutions all across the state, that are putting their lives at risk for not much more than minimum wage," Thompson said. "They still come to work every day and they still do their jobs every day. My appreciation for them has grown immensely."

"The family at St. Bernards is exceptional. Many have referred to them as heroes, and it describes them well," said Givens, who has been with the hospital for about 20 years. "Throughout this entire situation, they have done anything necessary to ensure that we take care of all patients."

VACCINE GIVES HOPE

To date, more than 130,000 Arkansans have received at least the first dose of the covid-19 vaccine.

Medical professionals -- an estimated 188,000, according to the Health Department -- were first in line. But not all of them took the shot.

The Health Department does not track who declined the vaccine.

Thompson said he's shocked and saddened when he hears of health care workers who refuse the shot.

"If only 40% of the population takes the vaccine, we are never going to get there," Thompson said. "I don't want to think about that and I don't want to think about another year of this."

McGee said she's discouraged by the amount of misinformation on social media about the vaccine's safety.

"There may never be an end to covid, but I definitely think the vaccine is our first step in returning to normalcy," she said.

"Individuals are tired, and public precautions have gone on for a long time. Our hope is that this community will continue following guidelines that reduce the spread of covid-19 and that more community members will take the vaccine as it becomes readily available," Givens said.

McGee said the greatest thing the public can do to support its overwhelmed health care workers is to follow safety guidelines -- get the vaccine, wear a mask and practice social distancing -- and to truly see the reality of covid-19.

"It's not just ruined get-togethers. It's not just ruined going to the movies and restaurants with tons of people. It has ruined lives," McGee said. "It's not just older individuals or patients that have been in hospice forever. It's moms. It's dads. It's brothers. It's someone's best friend. And it has taken way more lives than it should have taken."