Fred Otash, the protagonist (not to say hero) of James Ellroy's latest novel, was a real guy.

He was an infamous Hollywood fixer, the sort who brokered deals between agents of movie stars and gossip magazines to keep their clients' names out of their pages. He had been an L.A. cop before he became a highly paid private investigator, whose main line was "verifying" lurid stories for the scandal magazine Confidential.

He was allegedly the main inspiration for Jack Nicholson's "Chinatown" character, Jake Gittes. If you're interested in the lurid side of Hollywood, Otash's name comes up a lot.

Otash died in 1992, which made him fair game for Ellroy; dead men can't sue. Ellroy knew and debriefed Otash, who has appeared as a character in his work before. Ellroy was even tempted to cut a deal with Otash, to make him the star of his 1995 novel "American Tabloid," but he didn't trust the guy and instead went with a fictional protagonist.

Ellroy often puts historical characters to use in his novels, which taken together form an entirely plausible alternate history of 20th-century America. In "Widespread Panic," James Dean, director Nicholas Ray, singer Johnny Ray, Elizabeth Taylor, John F. Kennedy and Ingrid Bergman are some of the historical figures who might sue Ellroy were they alive.

None of them are portrayed in a flattering light, but you don't get the feeling they're being misused either. (That's not to say Ellroy won't occasionally hit a nerve — I reflexively objected when Paul Newman made an unbecoming cameo early in the book. Let's hope Tom Hanks outlives Ellroy.)

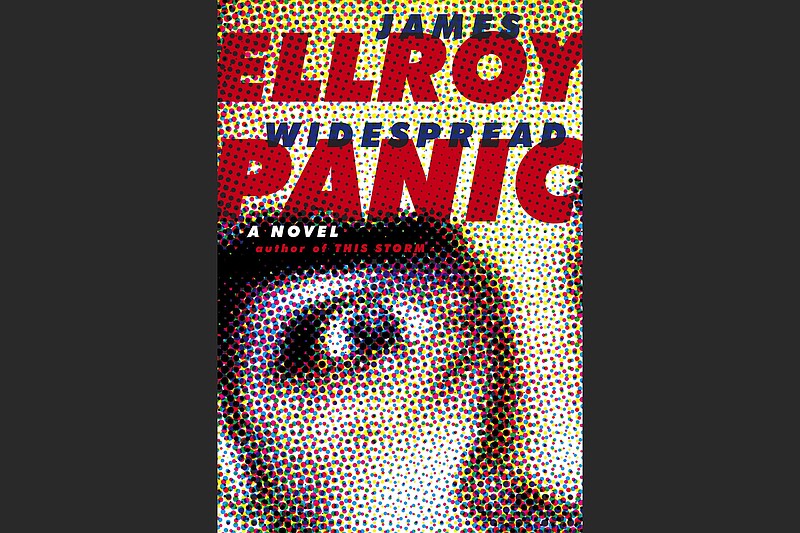

While "Widespread Panic" isn't among Ellroy's best work — it feels like a conscious step back from the high ambitions of his last two novels, 2014's "Perfidia" and 2019's "The Storm" — it is a mightily entertaining Black comic rap, a jivey spew of slanderous anecdotes in an exaggerated voice that, as stylized and staccato and arch with alliteration as it is, still manages to grow on you.

Ellroy writes with the authority of a minor god, and it's easy to believe in the stories he tells. Sometimes his work seems more credible than the agreed-upon facts, which is both dangerous in our present era of malleable facts and exciting if you still believe in the possibility of fiction to reveal deep things about the human condition.

This is where I say people who get their history from Ellroy's novels might be getting a truer version than is available in textbooks. Ellroy's lies cut so much closer to the bone.

In Ellroy's book Otash is not quite in hell, which might come as a surprise to a lot of people who knew and knew of him, and even to the man himself. Instead he has spent the past 28 years in purgatory, in a cell, a "f-----g hellhole." He wants out and so he has cut a deal: He'll spill all, giving his confession in exchange for his release. And so he spins the story of his glory days in the 1950s.

Otash is a crooked cop from the get-go, and when straitlaced William Parker becomes chief in 1950, Otash's corruption is exactly the sort Parker means to root out. So Otash resigns from the force, but not before sullying his soul by executing a suspect he believes is a cop killer.

But the wounded cop had pulled through, rendering Otash's actions rash and unrighteous. For years, he anonymously delivers "penance payoffs" to his victim's widow, but then she turns up dead — killed in an apparent burglary. Otash vows to avenge her.

He bribes an old buddy to get access to the police files on the investigation, and discovers she was a poor kid with a brilliant mind who took several degrees from the University of California at Los Angeles before inexplicably marrying the low-rent hoodlum Otash murdered. What gives? Digging further, he finds that she's connected to a Communist cell whose members have crossed Otash's path before.

"I'll do anything short of murder. I'll work for anyone but the Reds," Ellroy has his fictional Otash say a number of times. The real Otash told Mike Wallace on his TV show in 1957 that "I won't take a case for ... er ... a member of the Communist Party, or, a communist; I sort of draw the line there."

Otash is a self-described rat fink, but also a hopeless romantic. He's smitten by a lot of the women who cross his path — he has a crush on a 19-year-old University of Southern California basketball player who helps him baby-sit Liberace's leopard, and develops a kind of sweet thing with actor Lois Nettleton, another dead real person with whom Ellroy has been infatuated since he saw her in an episode of "Naked City" when he was 13 years old; he dedicates the book to her.

Otash pretended he only wanted the facts in his interview with Wallace, but Ellroy frankly doesn't give a whit about verification or plausibility. This is a different world, one of his creation, under his management; to enter it is to be theme park-thrilled and carny-conned.

It's not that different from Ryan Murphy's "Halston" and "Hollywood." It's probably not that different from Q-Anon or Scientology.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com | blooddirtangels.com