This year's South By Southwest Film Festival was entirely virtual, and supremely condensed, such that the whole festival -- films, conferences, talks, VR events -- took place in a scant five days. There was far too much to be able to take in at once, but I did get to see a decent number of films, which ranged in quality from phenomenal to barely watchable. Here's the first batch of capsules, with scores (from 1 to 10) relative to other entries in the festival. Part 2, next week.

"The Oxy Kingpins"

Score: 8

You can pretty easily see how a corporate drug baron of a company might want to play this: Get the actuaries to run scenarios where you make ungodly gobs of money for about 20 years, even if you know there will be a large death toll and public outrage by the end. Sure, you might end up paying some hefty fines, and a lower-level manager or two might get sent to the pokey for a bit, but at the end of the day, you'll still be looking at upward of a $150 billion profit margin, year after year until the public authorities finally catch up to you.

Brendan Fitzgerald and Nick August-Perna's documentary, "The Oxy Kingpins," begins with the second tier of profit-minded villains in the chain of command of the Oxy scourge that began in earnest in 1999, and has finally begun to peter out, two decades later. We meet Alex, a former drug dealer who did his time and now is trying to "do good," in the wake of the scandal. As the film opens, he's giving valuable intel to a Florida class-action lawyer named Mike Papantonio, a cagey veteran of similarly complicated cases (he was also the lead attorney in a major case against big tobacco in the '90s).

While its true Oxycontin's producer, Purdue Pharma, has plead out to a series of charges and fines, Papantonio and his formidable team are gathering information for his forthcoming hearing against another set of corporate behemoths who helped perpetuate the crisis: The major pharmaceutical distributors (McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen), who repeatedly looked the other way when it became increasingly obvious how much the drug was tearing the country apart. As Papantonio's team determines, the scheme worked like this: Purdue would produce millions of pills, and do enormous PR blitzes for the medical professionals to induce them to prescribe the highly addictive painkiller (as Alex puts it, Oxy is essentially heroin, and can leave most people badly addicted after only a couple of weeks); meanwhile, the distributors would, essentially, flood small-town markets with an insane amount of the drug (among other harrowing examples, try 3.1 million pills over the course of a year for a Nevada town whose entire population is 4,300), with the absolute intent that the massive surplus of pills would be "acquired" by underground dealers such as Alex, who could, in turn, make a massive profit themselves, given Oxy's potency.

In short, everyone made gobs of money in this deadly airplane scheme, from the drug's producer, to the distributors, to the doctors and pharmacies, down to the lowest-level dealers. Everyone, that is, except those suffering from its addictive properties, leading to loss of home, health, families, and all-too-often, life (the death toll over the last 20 years conservatively stands at 700,000). Legalized drug dealing, as Alex determines, with the unusually high casualty rate cast aside for a chance at enormous profit margins. Papantonio's case against the distributors, acting in concert with the Nevada attorney general's office, begins next month.

"Broadcast Signal Intrusion"

Score: 9

Creepy video movies are really only as good as the supposedly creepy videos upon which the plot hinges. Jacob Gentry's flick, "Broadcast Signal Intrusion," set in late '90s Chicago, offers a suitably disturbing suite of clips -- a seemingly robotic woman in heavy rubber masking makes inconclusive gestures against a peculiar living room backdrop and amid a cacophony of troubling sounds, electronic beeps, and indecipherable multi-tracked voices -- all of which become the obsession of a troubled young widower named James (Harry Shum Jr.), who works as a video tech in a cavernous basement office, endlessly transferring VHS tapes to the newer format DVD discs.

Still very much in grief over the loss of his wife -- even though he attends a suicide support group meeting, the film never makes it quite clear what happened to her -- James latches onto these mysterious tapes, which were somehow pirate broadcast over FCC-regulated airwaves on different stations, and quickly descends into the rabbit hole of early-internet BBS boards, racking down obscure theories with the help of a local college professor (Steve Pringle). Later, he meets up with a mysterious woman named Alice (Kelley Mack), who says she's "studying" him, and helps him dig even deeper into the increasingly unhinged, paranoid delusions from which he appears to be suffering.

As James burrows deeper in the metaphoric underground, he finds alternate solutions: One, in which he and Alice meet with a man (Chris Sullivan) who purports it to be essentially a high-school prank, which James quickly rejects; and another, in which he finds the elusive third tape, and somehow determines from it the location of the sociopath who made them as a confession to his sins. Gentry, working from an impressively taut script by Phil Drinkwater and Tim Woodall, creates a well-crafted sense of atmospheric dissonance -- his use of sound design coupled with the smartly designed soundtrack help to foster the growing unease -- that remains just ambiguous enough that we can never find firm footing, but not too obscure as to be impenetrable. Impressively accomplished.

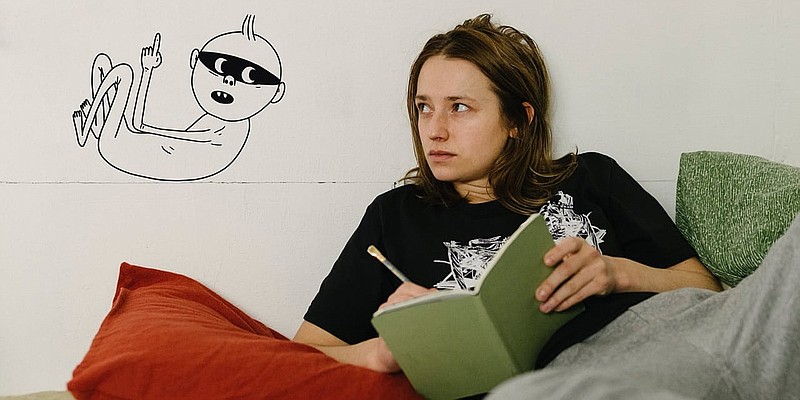

"Ninjababy"

Score: 8

Yngvild Sve Flikke's film, "Ninjababy," about a free-spirited young woman who discovers that she's pregnant, was a certified hit at this year's Berlinale, and, even a few minutes in, you can see why.

Rakel (Kristine Kujath Thorp) is an aimless 20-something, living with her best friend, Ingrid (Tora Christine Dietrichson), partying wildly, sleeping around indiscriminately, and living, for the most part, as if she were still in a college dorm somewhere. When her frequent trips to the bathroom and suddenly acute sense of smell leads her to take a pregnancy test, she's stunned. She assumes it had to have been from a night with a kindly Akito instructor named Mos (Nader Khademi) whom she met at a bar a few months before, who promptly offers to help her in any way he can.

Instead, to her shock and dismay, it turns out she's already 26 weeks into her term, meaning Mos is not the father, and now she has no choice but to go full term. The true father (Arthur Berning) turns out to be a jerk of a fellow whom Rakel and Ingrid have mocked for years. At first, he has no interest in raising a child, but some weeks later decides, in fact, he would make a great father after all.

There are other plot complications, including Rakel having offered her unborn baby to her half-sister (Silya Nymoen), who's been trying to get pregnant for years, but the film is mostly centered on Rakel, and her kicking and screaming into motherhood. A cartoonist, she creates a baby character (hence the title of the film) to act as a surrogate to her conscience, who floats around her during conversations, and plaintively asks her why she doesn't seem to care about him.

Flikke, who co-wrote the film along with Johan Fasting and Inga Sætre, adds animated visual flourishes (waiting sadly in the hospital and feeling wretched, Rakel is suddenly pelted with animated rain drops; she keeps mentally dusting everyone's head with dandruff from time to time) along with Ninjababy himself, but never overdoes it or falls prey to cute whimsy.

Far from a standard crowd-pleaser -- we've all seen the countless Hollywood versions of this particular growing up process (many of which seemingly made by Judd Apatow) -- Flikke's film, while often comic, isn't about trying to make everyone comfortable, exactly. From its ribald and descriptive body-horror language (Rakel is unashamed of bodily processes), to the way in which it eschews a traditional emotional growth arc for its heroine in favor of something a good deal more ambiguous. It may be funny, but it's hardly simple.

"Here Before"

Score: 7

Andrea Riseborough, an unassuming actress with a startling wealth of talent, has a particular penchant playing women on the edge of psychosis.

In "Here Before," writer/director Stacey Gregg's psychological drama, she plays a woman named Laura, living with her husband, Brendan (Jonjo O'Neill), and teenage son (Lewis McAskie) in a pleasant subdivision in Northern Ireland. Still grieving the loss of her young daughter in a car wreck some years back in which Brendan was driving, she takes a great interest in Megan (Niamh Dornan), a young girl who moves in next door with her mum (Eileen O'Higgins) and step-dad (Martin McCann).

In Laura's mind, it's pretty clear that Megan is her lost daughter, Josie, come back to her at last -- a belief only added to by Megan herself, as she seems to remember places and details that presumably only Josie could have known. As Laura gets deeper and deeper into this idea, the film seems to agree with her, at least as far as we can tell: Gregg peppers the film with snippets of other details, and pours on the atmospheric resonance until it's impossible to tell where Laura's growing psychosis begins, and where the narrative ends.

It's all very effective and creepy, anchored by another rock-solid turn by Riseborough, who does most of her character work with the subtleties of her expressions, the ways her eyes dart about, the angle of her jaw when she delivers a line, right up until Gregg inexplicably goes for a Hitchcockian twist, allowing the audience -- and Laura -- an out that we might not have been asking for. There's still plenty to admire here -- the cinematography by Chloë Thomson is outstanding, and the film makes interesting connections between the nature of our grief and the lengths we will go to bargain with it -- but it works much better in its ethereality than when it tries to make sense of it all.