LLANO, Texas -- In a growing number of communities across America, conservatives have mounted challenges to books and other content related to race, sex, gender and other subjects they deem inappropriate.

Conservative activists in several states, including Texas, Montana and Louisiana, have joined forces with like-minded officials to dissolve libraries' governing bodies, rewrite or delete censorship protections, and remove books outside of official challenge procedures.

In early November, an email from a citizen dropped into the inbox of County Judge Ron Cunningham, the head of the governing body of Llano County in Texas' Hill Country. The subject line read "Pornographic Filth at the Llano Public Libraries."

"It came to my attention a few weeks ago that pornographic filth has been discovered at the Llano library," wrote Bonnie Wallace, a 54-year-old local church volunteer. "I'm not advocating for any book to be censored but to be RELOCATED to the ADULT section. ... It is the only way I can think of to prohibit censorship of books I do agree with, mainly the Bible, if more radicals come to town and want to use the fact that we censored these books against us."

Wallace had attached an Excel spreadsheet of about 60 books she found objectionable, including those about transgender teens, sex education and race. The list included such notable works as "Between the World and Me" by author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, an exploration of the country's history written as a letter to his adolescent son. Not long after the email, the county's chief librarian sent the list to Suzette Baker, head of one of the library's three branches.

"She told me to look at pulling the books off the shelf and possibly putting them behind the counter. I told them that was censorship," Baker said.

Wallace's list was the opening salvo in a censorship battle that is unlikely to end well for proponents of free speech in this county of 21,000 nestled in rolling hills of mesquite trees and cactus northwest of Austin.

Leaders have taken works as seemingly innocuous as the popular children's picture book "In the Night Kitchen" by Maurice Sendak off the shelves, closed library board meetings to the public and named Wallace the vice chair of a new library board stacked with conservative appointees -- some of whom did not even have library cards.

With these actions, Llano joins a growing number of communities across America where conservatives have mounted challenges to books and other content related to race, sex, gender and other subjects they deem inappropriate. A movement that started in schools has rapidly expanded to public libraries, accounting for 37% of book challenges last year, according to the American Library Association.

"The danger is that we start to have information and books that only address one viewpoint that are OK'd by just one certain group," said Mary Woodward, president-elect of the Texas Library Association.

"We lose that diversity of thought and diversity of ideas libraries are known for -- and only represent one viewpoint that is the loudest," said Woodward, noting that there have been an estimated 17 challenges leveled at public libraries in Texas recently and that she expects many more.

Leila Green Little, a parent and board member of the Llano County Library System Foundation, said her anti-censorship group obtained dozens of emails from county officials that reveal the outsize influence a small but vocal group of conservative Christian and tea party activists wielded over the county commissioners to reshape the library system to their own ideals.

In one of the emails, which were obtained through a public records request and shared with The Washington Post, Cunningham seemed to question whether public libraries were even necessary.

"The board also needs to recognize that the county is not mandated by law to provide a public library," Cunningham wrote to Wallace in January.

He declined to comment for this story but said in a statement that the county was aware of citizen concerns and "is committed to providing excellent public library services to our patrons consistent with community expectations and standards, as well as operating within compliance of Texas and Federal statutes."

Cunningham strode into the main library a few weeks later and took two books off the shelves -- Sendak's "In the Night Kitchen" -- because some parents had objected to the main character in the story, a little boy, appearing nude -- and "It's Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health," a sex education book for parents and children ages 10 and up that includes color illustrations of the human body and sex acts.

He also ordered librarians to pause buying new material and to pull "any books with photos of naked or sexual conduct regardless if they are animated or actual photos," emails reviewed by The Washington Post showed.

OFFICIALS INTERVENE

Texas school districts already had many book challenges in October, when state Rep. Matt Krause, Republican chair of the General Investigating Committee, asked school districts for information on his own list of 850 books, most of them gender- and race-themed, that "might make children feel discomfort, guilt or anguish." Republican Gov. Greg Abbott jumped into the fray, calling for an investigation of "pornography" in school libraries. One school district removed more than 100 books, although most were reviewed and returned.

EveryLibrary, a national political action committee for libraries that tracks such challenges, said it has seen "dozens of new attacks" on libraries, their governing bodies and policies since the first of the year -- in Texas as well as ongoing cases in Montana and Louisiana. In some cases, the challengers are being assisted by growing national networks such as the parental rights group Moms for Liberty or spurred on by conservative public policy organizations such as Heritage Action for America, the American Library Association has said.

At the county's main library in Llano, director Amber Milum said in an interview that she had already taken it upon herself to put some books away in a file cabinet in her office as early as August, including two popular read-aloud picture books aimed at amusing kids: "I Need a New Butt!" and "Freddie the Farting Snowman."

The moves circumvented the library's established practices on objectionable content -- including a challenge form to be reviewed by librarians. Isolating or removing books because of subjective or personal opinions -- finding the content offensive or distasteful, for example -- could open up a library to a First Amendment challenge, experts said.

"We didn't fill out a form, everyone just came in and talked to me personally," Milum said. "I took notes on everything that everybody was saying, and that's how it happened."

Then in December, the commissioners voted to suspend the county's e-book system, OverDrive, because, they said, it lacked sufficient parental controls, which also cut off access to the elderly, people with disabilities or those otherwise unable to visit a physical library. Officials say they plan on replacing the system. They also shuttered the libraries for three days just before Christmas to review and reorganize the teen and children's collections.

"God has been so good to us ... please continue to pray for the librarians and that their eyes would be open to the truth," Rochelle Wells, a new member of the library board, wrote in an email. "They are closing the library for 3 days which are to be entirely devoted to removing books that contain pornographic content."

Green Little said little is known about what administrators did during the time the libraries were closed. The book "Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents," a work about systemic racism by Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist Isabel Wilkerson, has mysteriously vanished, and the fate of several other works remains unknown, she said.

'TAKE A BREATH'

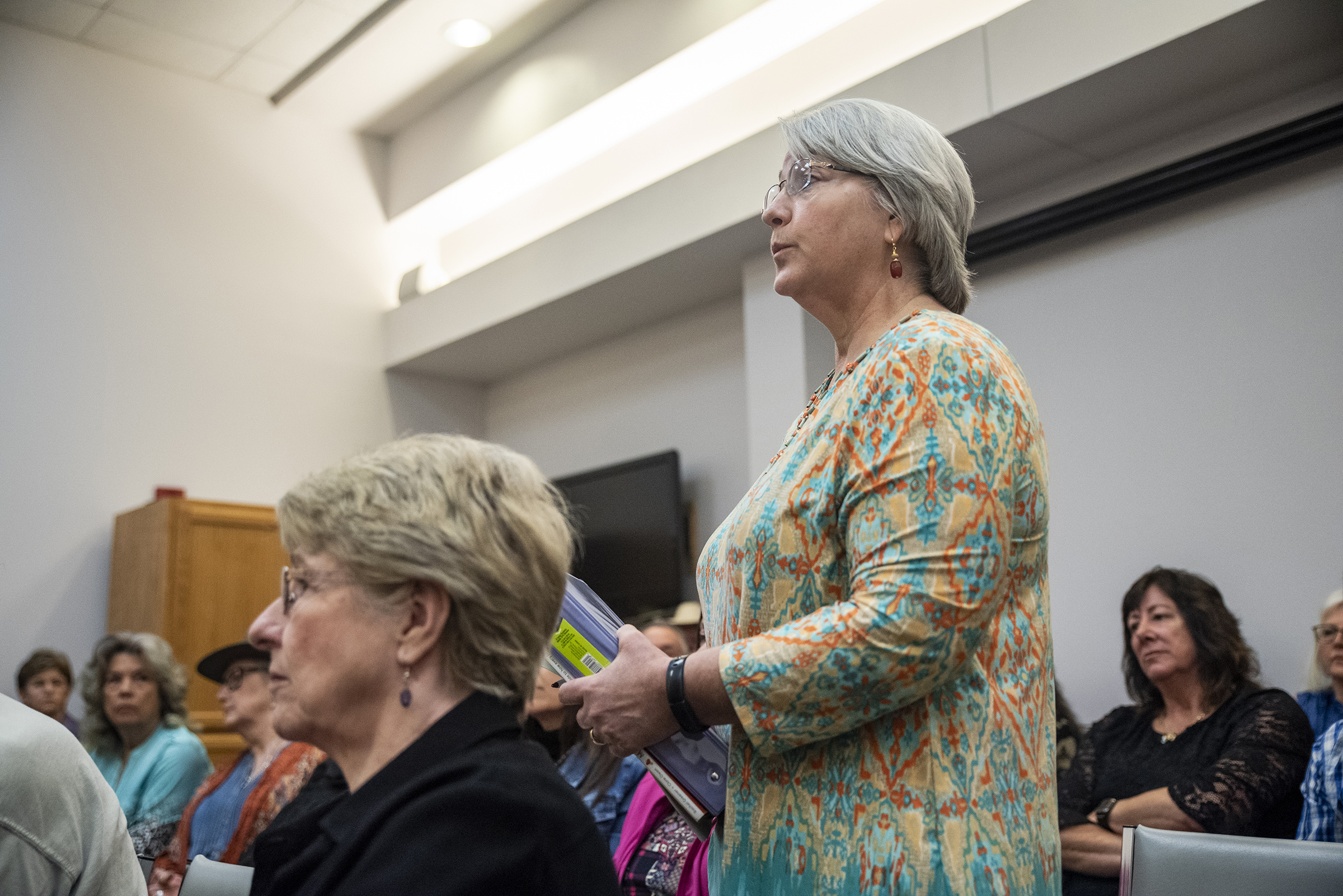

One recent spring day, an overflow crowd packed the Llano County commissioners meeting as the panel debated the new library advisory board's bylaws.

Many who spoke praised the commissioners for their recent work "saving the children of Llano County" from "pornography" and "pedophiles," often breaking into enthusiastic applause and shouts of "Amen!" Tension erupted when latecomers stuck in the hallway attempted to speak. "I'd like to speak in the name of Jesus!" one man yelled.

When Cunningham spoke, he evoked past trials that the county had weathered and a historic flood, a historic freeze and a historic pandemic.

"This has gone way too big and way too heated," he said. "Both sides need to take a breath. We're going to get to a solution together."

Throughout the debate, the commissioners deferred to Wallace, who showed up with an giant binder full of papers, including what appeared to be a color copy of an illustration from one of the offending books. Ultimately, each side scored a small victory -- the head librarian would now be a member of the board, as the anti-censorship camp wanted, but the meetings would be closed to the public.

Green Little's group is also consulting attorneys from the ACLU and elsewhere to see if there is any "legal accountability" for the commissioners' actions.

She said they will keep fighting, but "the things I feared already came true. I expect more of the same -- more censorship, more opacity, a library for all curated by the few."

Information for this article was contributed by Magda Jean-Louis of The Washington Post.