Quick, what movie won the Academy Award for Best Picture last year?

"Nomadland." Congratulations if you didn't Google.

Best actor?

Anthony Hopkins, for "The Father." Remember? Everyone expected the Academy to honor Chadwick Boseman posthumously, so much that Steven Soderbergh and the show's other producers switched up the order of the segments so that the telecast would end with the presentation of the Best Actor Oscar rather than Best Picture. (That was the first time Best Picture hadn't closed the show since 1972, when the final moments were given over to the presentation of an honorary Oscar to Charlie Chaplin.)

They wanted the show to resolve on a poignant final chord; instead they got anticlimactic dissonance. Hopkins wasn't in attendance. He probably wasn't even watching, seeing how he was in England and it was past his bedtime. Presenter Joaquin Phoenix mumbled an acceptance on his behalf.

(Hopkins did give a lovely late acceptance speech on Instagram the next morning that paid tribute to Boseman. Maybe for the first time ever, we had an actor telling the truth when he said he didn't expect an award.)

We probably shouldn't have been surprised. Even though the Oscars sometimes seem pretty easy to predict — lots of people seem to be able to correctly predict the winners of the major awards at a 70%-90% clip — upsets happen all the time.

British actors especially have a way of stealing Oscars from prohibitive favorites. Like when Eddie Redmayne won in 2015 for his portrayal of Stephen Hawking in "The Theory of Everything" when Michael Keaton was the sentimental favorite for his role in "Birdman." (The camera caught Keaton tucking away his Oscar speech after Redmayne won.)

So at least we know Price-Waterhouse (the firm is now officially known as PwC for PricewaterhouseCoopers) doesn't leak its tabulations. And that the Oscar voting is very unlikely to be rigged.

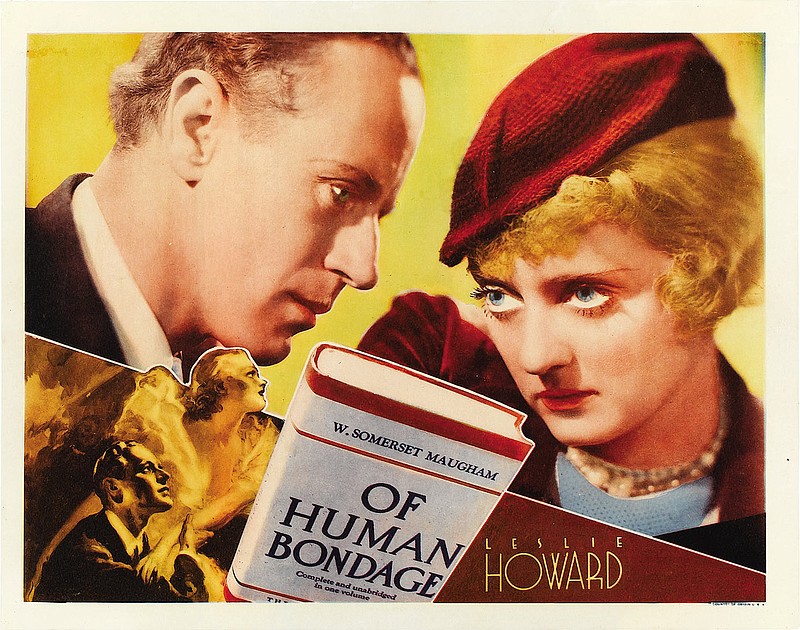

That wasn't always the case. If you think the Academy's use of an accounting firm to tabulate ballots is just so much self-dramatizing overkill, you might be surprised to learn that it was born of genuine scandal. In 1935, when Bette Davis was initially denied a Best Actress nomination for her work in "Of Human Bondage," neither she nor her public was willing to gracefully let it go.

WHY WAS SHE DENIED?

Davis thought she was denied a nomination because of studio politics and petty jealousy. Jack Warner didn't want to loan Davis, then under contract to Warner Bros., to rival studio RKO to make "Of Human Bondage," the film version of the William Somerset Maugham novel, for director John Cromwell in part because he thought the part — that of the slatternly and manipulative waitress Mildred Rogers — would damage her image. Which was precisely why Davis was determined to play the part.

"Many actresses are afraid that being typecast as a villainess can injure one's reputation," Davis later recalled. "... It was my ambition to play people exactly like her. So when I was offered that part by Mr. Cromwell in 1934, I told him, 'The right arm? Or the left?'

"At the time, however, Warner Brothers had other plans for me. They thought they needed me desperately for such immortal classics as 'Fashions of 1934,' 'The Big Shakedown,' and 'Jimmy the Gent.'"

Davis eventually made those movies, but continued to beseech Warner for the chance to play Mildred.

"I haunted Jack Warner's offices," she wrote. "Every single day I arrived at his door with the shoeshine boy."

After six months, Warner relented when RKO head Mervyn LeRoy agreed to make his contract player Irene Dunne available for the Warner Bros. production of "Sweet Adeline." The two studios essentially agreed to swap actresses.

At the time, Hollywood had not figured out what to do with Davis. Her talent was apparent, but she didn't fit the mode of the Hollywood ingenue. Warner Bros. had tried her in glamour roles, as the girl-next-door, as a demure professional, but nothing had yet clicked.

Warner may have legitimately thought that allowing her to play wicked Mildred would ruin her career; other actresses, like Katharine Hepburn and Irene Dunne, had turned down the part from that fear.

Davis' unflinching work (anticipating her work three decades later in "What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?", she did her own makeup and made herself look ill and hysterical) won her unprecedented praise — a critic from Life magazine called her work the best ever recorded by a film actress. (More importantly, it landed her in her niche, playing against audiences' sympathies as a strong and willful woman. A "shrew," by the lights of the day. "Of Human Bondage" is the first time Bette Davis plays a Bette Davis-type. While audiences hated her character, they did not transfer this antipathy to the actor. Davis was suddenly a star.)

But downbeat "Of Human Bondage" was not a box-office hit, and neither Warner Bros. nor RKO saw much point in pushing Davis for an Oscar. There were rumors Warner actively campaigned against Davis receiving a nomination. He had thought that by allowing her to make "Of Human Bondage," he was teaching her a humiliating lesson. That backfired, but he didn't want to actually reward her for being bullheaded.

ACADEMY DRAMA

At the time, each branch of the Academy voted to nominate within their speciality — actors voted for the acting nominees, directors for best director, etc. — with the winners coming from a poll of all members. And Davis was never terrifically popular with her peers.

Further complicating the situation was a feud between the Academy and members of the Screen Actors Guild, which had resulted in SAG demanding that its members resign from the Academy. So nearly half of the actors belonging to the Academy resigned, while those who remained were by and large studio loyalists beholden to the likes of Jack Warner.

When the official nominations were returned, the best actress nominees were Claudette Colbert for "It Happened One Night," Norma Shearer for "The Barretts of Wimpole Street" and Grace Moore for "One Night of Love." Davis wasn't among them, and was pretty ticked off about it.

Then Hollywood Reporter demanded to see the votes and launched a campaign for Academy members to write in Davis' name on their ballots. Photoplay quoted mail carriers as wondering how Davis could not have been nominated. The Academy was flooded with telegrams from Hollywood celebrities — including Shearer — demanding that Davis be considered for the award. It was a huge deal, and not just among the Hollywood cognoscenti.

In February 1935, the Academy announced its members would be allowed to write in the names of anyone they chose, and that these write‑in votes were then counted exactly as the votes for the official nominations.

Davis announced she'd be attending the awards ceremony anyway. Colbert, Shearer and Moore said that, in that case, they'd just as soon skip the banquet.

"The air was thick with rumors," Davis wrote in her memoirs. "It seemed inevitable that I would receive the coveted award. The press, the public and the members of the Academy who did the voting were sure I would win! Surer than I!"

She finished third, losing to Colbert, who at the moment the award was announced, was sitting in L.A.'s Union Station, waiting to board a Super Chief train for Chicago. (Union Station was where Joaquin Phoenix was standing when he announced Anthony Hopkins had won Best Actor last year.)

Colbert's performance as spoiled heiress Ellie Andrews in "It Happened One Night" is delightful, though she can be forgiven for not thinking much of her chances. After the film wrapped, she reportedly told a friend she had "just finished the worst picture in the world."

This did not sit well with Bette Davis.

A MAKE-UP CALL

"Syndicated columnists spread the word 'foul' and the public stood behind me like an army," Davis wrote. When she won the award for "Dangerous" the very next year, Davis considered it a make-up call. She said that she would have given the award to Hepburn, who finished second in the voting that year, for her work in the George Stevens' romance "Alice Adams."

"It was hardly inspiring," Davis wrote of the film. "It was maudlin and mawkish, with a pretense at quality which in scripts as in home furnishings, is often worse than junk."

But "Dangerous" was Warner Bros.' first attempt to cast Davis in the same sort of bad-girl role as "Of Human Bondage." So Warner was happy to push "Dangerous."

After the scandal of 1935, the Academy hired London-based accounting firm Price Waterhouse to count votes, to ensure the secrecy of the results, and "stem the tide of unfavorable industry sentiment." The New York Critics Circle was formed to bestow alternate awards untainted by studio politics.

The 1936 awards not only saw Davis receive her consolation Oscar; it also spelled the end of the short-lived write-in era. When Hal Mohr won for Best Cinematography for "A Midsummer Night's Dream," his victory blindsided members of the technical branch of the Academy.

Mohr was an industry veteran whose write-in campaign was pushed hard by, once again, Jack Warner. The feeling among Mohr's peer groups was that the award was, at best, a career achievement award.

They feared that technical awards might come to be mere popularity contests dominated by studio favorites.

We all understand Oscars are only incidentally bestowed on ageless work; politics and fashion and the desire to see a story played out all have as much to do with whether an actor or director wins as does the actual quality of the work. But at least it's an honest ballot.

WHO CARES?

Fewer and fewer people care about the Oscars; last year's Academy Awards telecast had its lowest television ratings ever (around 9.85 million total viewers, down 58% from the 2020 broadcast). Part of that was due to the ongoing pandemic, but at least some is due to the decreasing importance of the movies in our lives.

I can't claim to have seen all 10 of this year's nominated pictures — I'm missing Steven Spielberg's "West Side Story" — and few of us have seen what appears to be this year's frontrunner for Best Picture — Jane Campion's "The Power of the Dog" — in an actual theater.

Another Netflix film, Adam McKay's "Don't Look Up," is a dark horse contender; maybe the second favorite for the big prize.

A year ago we thought we'd be free of covid-era restrictions by now; we didn't expect this awards season to be particularly affected. But a lot of film festivals are still virtual, and though there are more channels that need content these days, it's getting harder and harder for small films to break through to the public consciousness. (Case in point, maybe the best 2022 film I've seen so far is "Help," which stars Jodie Comer ("Killing Eve"), and all of Sundance will be virtual.

Smaller films will take the hit. Arthouse films don't do as well when they don't get seen by those very appreciative festival audiences.

It seems the only movies that really do theatrical business now are on the order of 2021 box office champion "Spider-Man: No Way Home." And that's fine; the theaters will take the spectacle and the date-night teenagers, and the movies for grownups will migrate to smaller screens and streaming services, and the economical forces will re-align, and in a few years no one will remember what a movie star, or an Oscar, ever was.

I miss Bette Davis.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com