Veronica Bennett presented as a bad girl.

Which she might have been, growing up as she did in Spanish Harlem with an Irish-American father and a mother half Black and half Cherokee. "Half breed" wasn't all she ever heard. She heard "high yellow" as well. In the 1950s, being multiethnic didn't have the cachet some attach to it today.

She might have learned how to fight. But she didn't. When she was picked on, her mother made her stay inside to avoid the neighborhood kids. So she sang, with her sisters and cousins, because she could. Her whole family was musical. And too poor to afford roller skates.

At first there were a few of them, maybe six, who together sang doo-wop. Ronnie especially liked Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers — they did all their songs. They started out playing bar mitzvahs and sock hops, sometimes with cousin Ira, doing his Frankie impression. But when they played amateur night at the Apollo Theater, Ira froze up. The music started, but Ira couldn't.

Ronnie could do Frankie better than he did anyway. She had the piercing falsetto and vocal swoops in her back pocket. So Ira slunk away in shame — the group coalesced into the Darling Sisters, then Ronnie and the Relatives, and finally the Ronettes — for Ronnie, her cousin Nedra Talley and older sister Estelle. They played some shows for Murray the K, and even though they didn't have a hit record, they got a bigger reaction than the Shirelles or the Chiffons.

Because the Ronettes presented as bad girls. Not for them were the party dresses of the Shirelles. The Ronettes wore skin-tight dresses with slit skirts — "Chinese dresses," they called them — on stage.

They looked provocative, exotic, maybe a little dangerous. Ronnie had that New York accent and, despite her cloistered childhood, a whiff of the street about her. But in the beginning, it was the look more than the sound that set them apart — it's instructive that their big break came when they were hired as dancers, not singers, to perform with Joey Dee and the Starliters at the Peppermint Lounge.

One night, guitarist David Brigati noticed that Ronnie was singing along to their cover version of Ray Charles' "What I'd Say" and handed her a microphone, maybe as a joke. But it wasn't, and the Ronettes soon landed on Colpix records and released a few sides that went nowhere. So Estelle called Phil Spector, asking for an audition. To her surprise, he said sure.

The Ronettes sang for him in a New York studio. First they tried out their best recital harmonies, and Spector was unimpressed. So they broke out the Frankie Lymon and sang "Why Do Fools Fall in Love." That impressed him. He took Ronnie and Estelle back to their apartment on 151st street and met their mother. "Mrs. Bennett, I'm going to make a No. 1 record with your daughters."

In a sense, Spector's famous "Wall of Sound" was a simple idea. He crammed a small symphony orchestra into the studio, employing several acoustic and electric guitarists, two or three pianists, two bassists, two drummers, a handful of percussionists, background singers and more on each track.

Layers would be overdubbed over layers until the individual instruments seemed to merge and bleed into one greasy, pounding wave of noise. This created a signature sound, far more distinctive than the voices of the interchangeable lead singers that rode on top of the crescendo.

But Ronnie was different; hers was the voice he'd been looking for, different from the gospel-trained vocalists (like Darlene Love and the Crystals' Barbara Ann Alston) he'd been working with. There was something snide and sensual in her voice. There was sex in her voice.

In July 1963, 18-year-old Ronnie flew to Hollywood for a session at Gold Star Records, with its famous echo chamber. Hal Blaine was the drummer, and he started it off with a "bum-de-bum-BOOM" figure that would live in infamy. (He later said it was a mistake; he meant to play the snare on the second beat as well as the four, but muffed it. So he pretended it was what he intended all along. After the record came out, everybody wanted the "Be My Baby" beat. Nearly three years later, Blaine played it softly in the session for Frank Sinatra's "Strangers in the Night." It has been used in hundreds if not thousands of songs since.)

And then Ronnie came in with "The night we met I knew I needed you so." Magic, right?

Actually, no. It took three days to record her vocals, which she had rehearsed for weeks back home in New York. And after those countless takes — and Spector insisted on full performances; he didn't trust or like edits — she was banished from the studio, probably because Spector was jealous of the band ogling her.

He had celebrity drop-ins in the control booth shaking tambourines. He had his go-fer, a songwriter named Sonny Bono, and Sonny's girlfriend/housekeeper Cher Sarkisian singing backing vocals.

He made the orchestra do 42 takes before he was satisfied.

Ronnie was just one instrument among dozens. A special instrument, a rare and precious thing to be sure, but just part of the ensemble.

He didn't keep his promise to Ronnie's mom. "Be My Baby" only went to No. 2.

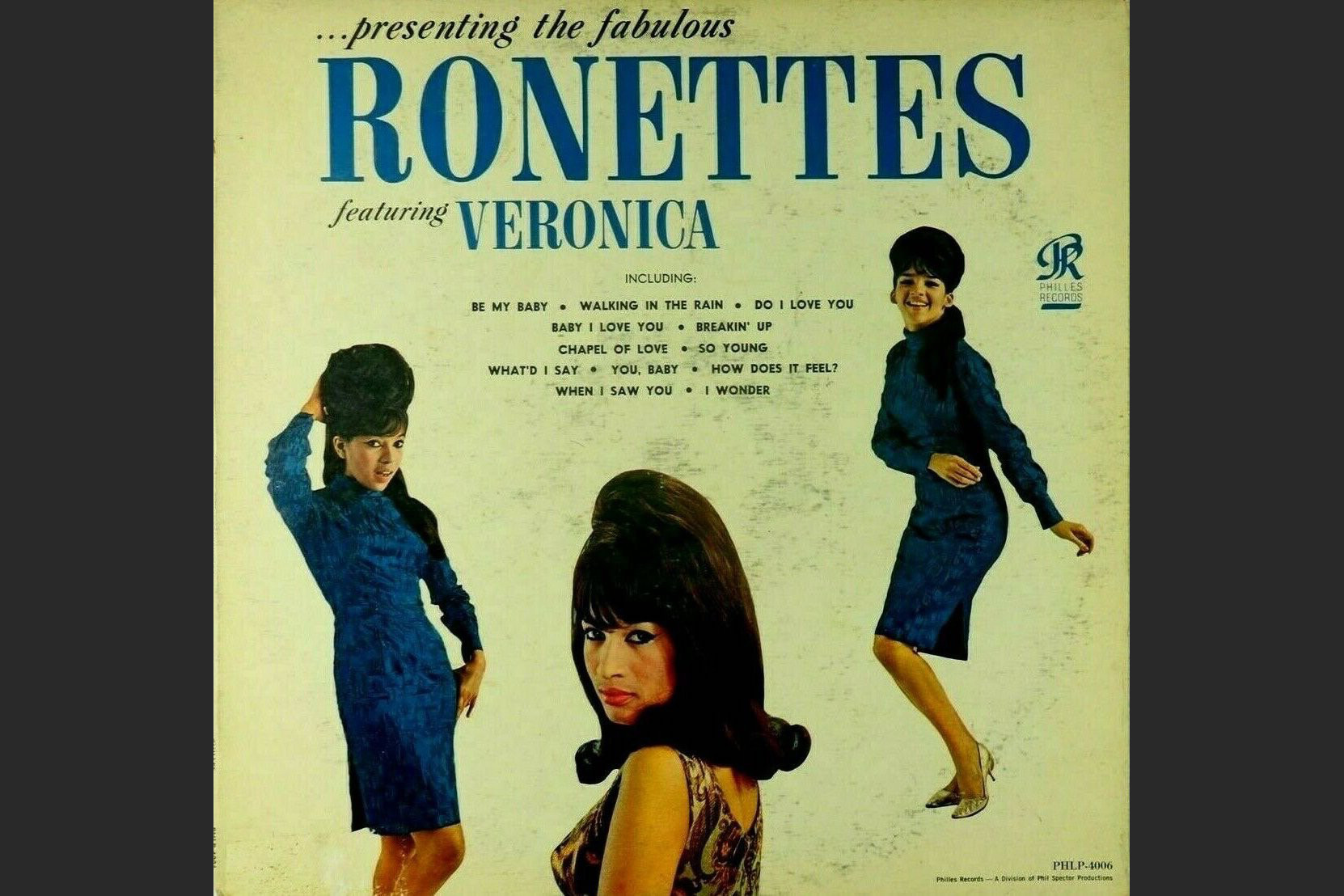

The Ronettes’ debut album, featuring Estelle Bennett, Ronnie Bennett and Nedra Talley. Nostalgia compresses time; everything in our past feels like it is in one place. I hear "Be My Baby" as a response to the call of the goody-good Shirelles' "Will You Love Me Tomorrow."

The Ronettes’ debut album, featuring Estelle Bennett, Ronnie Bennett and Nedra Talley. Nostalgia compresses time; everything in our past feels like it is in one place. I hear "Be My Baby" as a response to the call of the goody-good Shirelles' "Will You Love Me Tomorrow."

You might know that song from Carole King's 1971 version, recorded a decade after the Shirelles had the hit, slowed down, with James Taylor and Joni Mitchell on backing vocals. But the tremulous original is quite a record, evincing self-doubt and tentativeness, an emotional conundrum that's vastly more complex than most pre-Beatles rock 'n' roll:

- Is this a lasting treasure

- Or just a moment's pleasure?

- Can I believe the magic of your sighs?

- Will you still love me tomorrow?

Shirelles' lead singer Shirley Owens didn't initially want to record the song — written by King with her then-husband and Brill Building songwriting colleague Gerry Goffin — because she thought of it as "too country." She only relented when she heard the string arrangement producer Luther Dixon had come up with for the track.

"Will You Love Me Tomorrow" was the first single from the early '60s girl group boom to hit No. 1, and unlike some other chart toppers from the same period, it's a stellar piece of pop craftsmanship, with Owens' lead vocal sitting perfectly in the mix, poised yet yearning for affirmation.

What makes it great is its lack of operatic anguish — she's not bargaining, she's just making her concerns explicit. She's going through with it — be it her ruin or their deliverance. But it's all about the guy's desire.

With "Be My Baby," Ronnie took charge, assuring her would-be lover that together they'd be setting fire to the world:

We'll make 'em turn their heads every place we go.

"Will You Love Me Tomorrow" might have been the furthest thing from Ronnie's mind when she sang "Be My Baby." She didn't write the song — that was Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry and Spector. She was just the voice. The record was credited to the Ronettes, but she was the only one who sang on it. Estelle and Nedra stayed home in New York.

Phil Spector with The Ronettes — Nedra Talley, Estelle Bennett and Ronnie Bennett, later Ronnie Spector. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) As a group, the Ronettes were done by late 1967; Estelle married their road manager and went solo, recording "The Year 2000/The Naked Boy." She went on to front another girl group called The Love Chain. She had bad luck in the next decades, winding up on the street for a while, a former high school valedictorian panhandling on the streets of Manhattan, telling tourists she was singing with the Ronettes that very night if she could just make bus fare to the show. Though she was too weak to perform, she was on the stage when the Ronettes were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2007. She died in 2009.

Phil Spector with The Ronettes — Nedra Talley, Estelle Bennett and Ronnie Bennett, later Ronnie Spector. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette) As a group, the Ronettes were done by late 1967; Estelle married their road manager and went solo, recording "The Year 2000/The Naked Boy." She went on to front another girl group called The Love Chain. She had bad luck in the next decades, winding up on the street for a while, a former high school valedictorian panhandling on the streets of Manhattan, telling tourists she was singing with the Ronettes that very night if she could just make bus fare to the show. Though she was too weak to perform, she was on the stage when the Ronettes were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2007. She died in 2009.

Nedra married a DJ and got into Christian music, and then real estate. She's doing just fine.

Spector wanted to possess Ronnie from the very beginning. Having found that voice, he was determined not to let it go. He limited the Ronettes' touring schedule, famously preventing them for opening for the Beatles. He married Ronnie and forced her to essentially retire in 1968.

Ronnie only sounded indomitable. She was just a girl from Spanish Harlem after all, a disembodied voice on the radio.

He locked her away, behind barbed wire, in a Spanish castle in the hills above Doheny Drive. He confiscated her shoes. He'd let her out once a month to shop, but if she was gone for more than 20 minutes he'd send his bodyguards after her. He was violent and abusive and had a thing about guns. One year, as a Christmas gift, he presented her with adopted twin sons.

Finally, after four years, she escaped, with the help of her mother, barefoot with only the clothes on her back. She walked to a divorce lawyer.

She tried to mount a comeback, but Phil Spector was still a powerful man in the industry. He prevented her from singing her old hits — she couldn't perform "Be My Baby" in public. In 1998, she testified that she signed a 1974 divorce settlement under duress; Spector had said he'd kill her if she didn't. Under that agreement she forfeited all future earnings from the Ronettes' recordings. (In 2001, a New York court ordered Spector to pay $2.6 million in back royalties to the Ronettes.)

"Phil threatened me several times," Ronnie testified in Manhattan Supreme Court. "He told me, 'I'll kill you' and 'I'll have a hit man kill you.'"

Some people thought, well, people say hyperbolic things during divorce proceedings. This was five years before Lana Clarkson would be shot to death in another of Phil Spector's Hollywood mansions.

■ ■ ■

There was a comeback, but it was a long climb. In the early '70s, it was possible to believe that Ronnie Spector — she kept her married name for professional reasons, because she needed people to remember her — had been some sort of pop chimera, that she was mythic. But she still got work, here and there.

There was a reformed Ronettes with two new members, but that didn't take hold. She tried to launch a solo career, but her highest profile work of the '70s is likely "You Mean So Much To Me," her 1976 duet with the Bruce Springsteen-adjacent soul singer Southside Johnny.

That same year she released a cover version of Billy Joel's "Say Goodbye to Hollywood," which not only employs the "Be My Baby'" beat but imitates Spector's Wall of Sound production. Joel has said he wrote the song with Ronnie in mind.

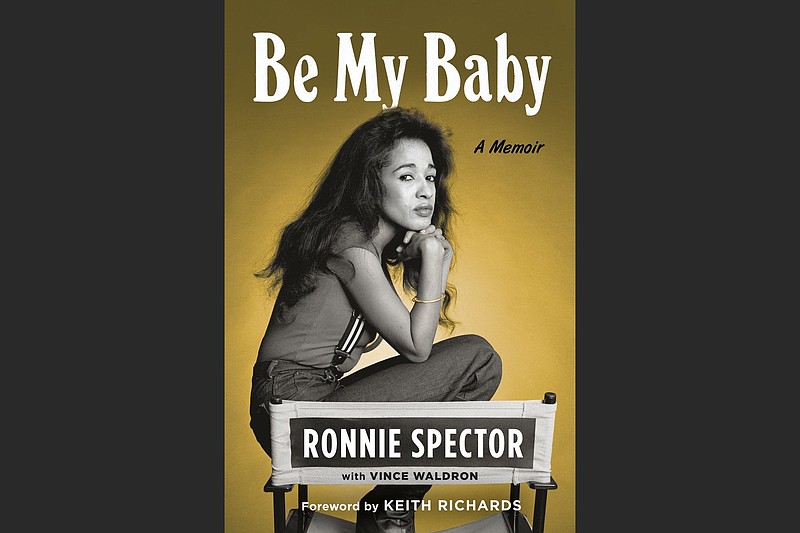

In her out-of-print 1990 memoir "Be My Baby: How I Survived Mascara, MiniSkirts and Madness or My Life as a Fabulous Ronette," Ronnie noted that it was ironic that she was perceived as an oldies act during much of the '70s and '80s even as she was prevented from performing her old hits. Finally, she got a bump of the big time when she contributed backing vocals on Eddie Money's 1986 sing "Take Me Home Tonight."

In the chorus, Money starts a line, "Just like Ronnie sang ... "

And Ronnie answers, "Be my little baby."

Shivers.

Money told Hippo Press, a New Hampshire alternative weekly, that he had wanted Ronnie to sing the line since his producer Richie Zito brought him the song. But Ronnie remarried in 1982, and was busy raising a family. Still Money persisted, eventually tracking her down and calling her California home.

"I could hear clinking and clanking in the background," Money said. " ... She said 'I'm doing the dishes, and I gotta change the kids' bedding. I'm not really in the business anymore, Eddie. Phil Spector and all that, it was a nightmare' ... I said 'Ronnie, I got this song that's truly amazing and it's a tribute to you. It would be so great if you ... did it with me.'"

After "Take Me Home Tonight" hit the Top 5, Columbia offered her a contract, and she made the album "Unfinished Business," her first recording since 1980.

"I could tell within two weeks [of the record's release] that it was a flop," she wrote in her memoir. " I know the excitement that happens when you've got a hit — the telephone rings off the hook, and everybody wants a piece of you. But none of that was happening."

There never was a real comeback; she released a smattering of recordings over the years, performed live, guested on other artists' tracks and never topped that first indelible moment when she exploded into the American consciousness, when she presented as rock 'n' roll's original bad girl.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com