A labor contract for 22,000 U.S. West Coast dockworkers is on the verge of expiring, opening the door to strikes, lockouts or work stoppages -- but both sides still appear willing to avoid such disruptions amid the busiest season of the year for shipping.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the more than 70 employers represented by the Pacific Maritime Association started May 10 negotiating a fresh contract for longshoremen across 29 ports in California, Oregon and Washington. While the current agreement ends today, the groups have recently said they're unlikely to reach a deal before then and reaffirmed neither side is preparing for a strike or lockout.

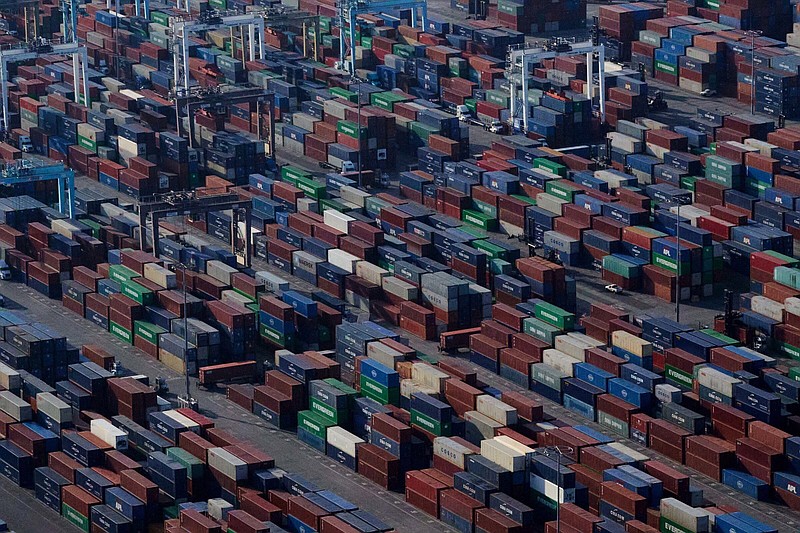

The ports handle just under half of the containers entering and leaving the U.S. and are the principal gateway for shipments to and from China, the biggest source of American merchandise imports -- illustrating the high-stakes nature of the negotiations.

In November, the union declined an offer by the association to extend the current contract until July 2023. The current pact was originally set to end in 2019, but was lengthened after roughly two-thirds of union members voted to do so in exchange for higher wages and pensions.

Now, one possible option is that both parties agree on a short-term contract extension to preserve the current deal's no-stoppage clause as negotiations continue. At the Port of Los Angeles, Executive Director Gene Seroka isn't expecting a strike.

"Anything's possible but it will not happen," Seroka said on Bloomberg Television. The port is giving the union and employers "as much room as they need to negotiate and the rest of us are just moving all this cargo through the nation's largest gateway."

Talks often go beyond the expiration date, and the parties' commitments to keep cargo moving could avoid a repeat of the delays and congestion that hampered ports previously.

This time around, the negotiations are drawing attention because the nation's largest trade hubs -- the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach -- are struggling to clear pandemic-era congestion.

The economic stakes are high: July and August are typically busy months for imports from Asia as retailers stock up on back-to-school and holiday goods. The peak has arrived even earlier this year, with companies looking to preempt future disruptions by ordering these products even further ahead of time.

Additional transportation snarls would only add to the inflationary pressures.

They will also test how far a major union will apply its bargaining leverage during an economic slowdown, given the country is facing a moment of unusual clout for its long-declining labor movement.

Anticipating problems, some shipping companies have rerouted services to ports on the East Coast, resulting in longer queues from Savannah to New York, according to a recent tally from Hapag-Lloyd, Germany's largest container line.

The hardships of laboring through the covid-19 pandemic, employers' recent robust profits, and the rapid acceleration in inflation could all drive up union members' expectations for winning substantial raises.

The focus on mitigating supply-chain disruptions and the near impossibility of running the ports smoothly without these workers could embolden them to seek bigger concessions.

Several scenarios are possible, said Julie Gerdeman, chief executive officer of supply-chain risk analytics firm Everstream Analytics. Instead of a full strike, ports would most likely see a slowdown in loading and offloading operations, similar to 2014.

"This would slow down West Coast port operations at a time when we will likely see an uptick in imports from Asia," Gerdeman said.

Labor impasses are contributing to supply-chain disruptions worldwide. Korean industries have faced production woes because of a weeklong trucker union strike in June. Protests have also emerged in Germany, the U.K. and Argentina.

Meanwhile in the United States, major railroads are also struggling on the labor front, as two years of unsuccessful negotiations could force the White House to intervene and prevent a strike.

If there are difficulties at West Coast ports, President Joe Biden could be forced to invoke the Taft-Hartley Act, a Cold War-era law that allows the government to call for an 80-day cool-down period amid labor impasses.

Then-President George W. Bush relied on the legislation to reopen the ports in 2002, after the PMA locked out workers for 10 days following a series of work slowdowns. When the union carried out the longest strike in U.S. longshore history for 130 days in 1972, Richard Nixon did the same.

"The administration has been watching this very closely ever since they came into office," Seroka said, adding Biden's June meeting with the negotiating parties was likely the first by a sitting president during contract talks.