Night fell quickly, as it does in the tropics. The only sound was the splashing of waves against the Zenith's hull and the halyards making music against the mast in the breeze. The shadows of manta rays glided beneath the catamaran, flapping their wings in the Caribbean currents. Within a coconut's throw of the boat, a palm-fringed island was perfectly silhouetted on the horizon. We made our way to the bow, where we flung ourselves onto the deck and looked up. The sky wasn't just streaked with stars; it was so luminous, it looked opaque, the constellations clearly etched in glowing pearls of light.

We were out in the world again, and it was glorious. For four nights last winter, my college roommate and I sailed through the remote Panamanian archipelago that we'd dreamed about for nearly 20 years. The islands are part of an autonomous region governed by the Guna, an Indigenous people who have inhabited the Isthmus of Panama since before the age of Spanish explorers. A matrilineal society, the Guna are custodians of the region's pristine natural beauty.

I first heard of the San Blas Islands as a 20-something backpacker. In those pre-Instagram days, travelers' tales spread across the hammocks of guesthouses, through shared Lonely Planet guidebooks, over beers at neighborhood bars and down the aisles of the so-called chicken buses traversing Central America. Sprinkled off the Caribbean coast of Panama was an Eden-like archipelago with so many tropical cays there was one for each day of the year. Like the idyllic island mythologized in Alex Garland's 1996 cult novel, "The Beach," which was later made into a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio, the San Blas irresistibly beckoned, tantalizingly difficult to access. Their isolation only enhanced the allure. Even when I later lived and worked in Central America, I never made it to the San Blas.

During the dark throes of the pandemic, when the four walls of my apartment felt as if they were closing in, I looked at maps and dreamed of the globe. It was my college roommate who pinpointed the far-flung destination neither of us had ever been able to reach. And so we began to plot an adventure. Anticipation can feel like that first cup of coffee on a groggy morning. For many months, looking forward to the trip gave me a jolt of hope and optimism every day.

The Guna people travel among the idyllic islands by boat, some fashioned as dugout canoes. (The Washington Post/Mary Winston Nicklin)

The Guna people travel among the idyllic islands by boat, some fashioned as dugout canoes. (The Washington Post/Mary Winston Nicklin)

ISLAND HISTORY

According to oral histories, the Guna are originally from the Darien mountains straddling the border of present-day Colombia and Panama. Intertribal conflict led to the gradual migration to the islands, a geographical location that induced fateful encounters with successive waves of invaders: conquistadors, pirates, privateers, gold diggers and, later, drug smugglers. Historians debate the exact timeline of the first Guna settlement on the San Blas; a more precise date is the Guna revolution of 1925 against the Republic of Panama. In the resulting peace treaty, Guna leaders agreed to be part of Panama as long as tribal laws were respected and customs were protected.

Today, the official name of the autonomous region is Comarca de Guna Yala, although the area is still known to many around the world as the San Blas Islands. It stretches more than 230 miles along the Caribbean coast. The Guna inhabit only about 50 of the islands, living in a traditional, communal way in thatched huts topped with palm-frond roofs. (The more populous community islands are packed with houses made of concrete and corrugated metal roofs.) The primary livelihood is fishing and coconut trade with Colombia; some of the population also lives on the mainland to cultivate crops such as yams, yucca, bananas and pineapple. The Congreso, the Gunas' ruling body, dictates strict laws to conserve the Guna culture and protect the land. Outsiders are forbidden to own property or harvest conch and lobster. Tourism revenue is generated from permits and island visitation fees. Scuba diving is not allowed.

There's just one road into the port of Carti, gateway to the islands. Navigable by 4x4s in daylight, the track is notorious for potholes, steep drops and washouts. Intrepid travelers are then funneled into Guna-operated water taxis, which ferry them to the tourist islands, where they can stay overnight in a hammock or cabana.

But there's another way to explore this halcyon marine world. Sailboat charters allow access to the hard-to-reach outlying islands, where the sole human interaction may be with Guna fishermen. A few primitive airstrips can accommodate small planes, which connect visitors to their boats. We arranged our charter through San Blas Sailing, which offers a range of all-inclusive boat categories and focuses on sustainability by training Guna crew members. (The busiest sailing period is December to April, the "dry season.") The French co-founder, Bernard Chemier, first came to the San Blas Islands 22 years ago on an around-the-world family sailing trip and never left. "The San Blas are unique because of the authenticity of the people, the beauty of the sand beach islands and their coral reefs, and the fact that Panama is hurricane-free," he later told me.

While the islands are strictly protected by the Guna’s governing body, the regulations can’t stop climate change: Several islands are disappearing as sea levels rise. (The Washington Post/Mary Winston Nicklin)

While the islands are strictly protected by the Guna’s governing body, the regulations can’t stop climate change: Several islands are disappearing as sea levels rise. (The Washington Post/Mary Winston Nicklin)

AERIAL VIEW

From the air, the jungles of Panama unfurled in a luxuriant green tapestry. We didn't see towns or power lines or roads crisscrossing the wilderness — just a rolling expanse of old-growth tropical forest abutting the sea. In fact, the country has set aside about 30% of the land in protected natural areas. And the Comarca de Guna Yala is so pristine that its mainland coast conjures a primeval world. This was especially evident at night, void of the light pollution of city settlements. From the Zenith, the forested shore loomed like the last frontier.

Captain Fred Ebers exuded the calm, pleasant demeanor of the most experienced sea captains. After a career as a consultant for the maritime industry all over the world, Ebers bought his French-made catamaran in Tortola and sailed across the Caribbean to Panama. Government maritime charts of the San Blas Islands haven't been updated for decades and are unreliable, making navigation difficult. So before launching his charter business aboard the Zenith in 2016, he sailed alongside veteran captains to learn the ropes. His own charts are annotated with the wisdom he has accumulated over the years. He has also learned to adapt to the Congreso's changing rules. Helping out as crew was Marina, the fun marinera, or hostess, who prepared delicious, copious meals.

Our days on the water were punctuated by visits from the Guna, who recognized the sailboat and pulled alongside in their skiffs — fashioned from dugout canoes, sometimes sail-powered — to sell fish, bananas and freshwater in barrels from the Rio Azucar on the coast. Whether buying their wares or not, Fred always offered our guests a cold drink and conversation. For a special meal, he sent a WhatsApp message to a Guna fisherman, who arrived with the largest Caribbean spiny lobsters I've ever seen — deftly prepared for grilling right before our eyes.

But perhaps the most wonderful morning was one we spent with a Guna family who arrived with a boatload of molas, the magnificent embroidered handicrafts for which the Guna women are known. Originally, the patterns were inspired by traditional body painting, translated into colorful textiles in reverse applique worn as panels on women's blouses. Requiring at least a week of work, the molas pay homage to the natural world that's so venerated in the culture: a menagerie of crabs and sea turtles and fish outlined with bold, geometric patterns. The mother spread out the cloth rectangles on the catamaran's deck table, explaining the prices to her Spanish-speaking husband, who translated from the Indigenous language, while her six kids quietly drank juice. We took our time admiring the artisanal beauty — the brilliant hues juxtaposed against the shades of blue surrounding us — before making the tough decision of which ones to buy.

A Guna fisherman arrives at the Zenith with his fresh catch: enormous lobsters, which can be grilled right on the beach. (The Washington Post/Mary Winston Nicklin)

A Guna fisherman arrives at the Zenith with his fresh catch: enormous lobsters, which can be grilled right on the beach. (The Washington Post/Mary Winston Nicklin)

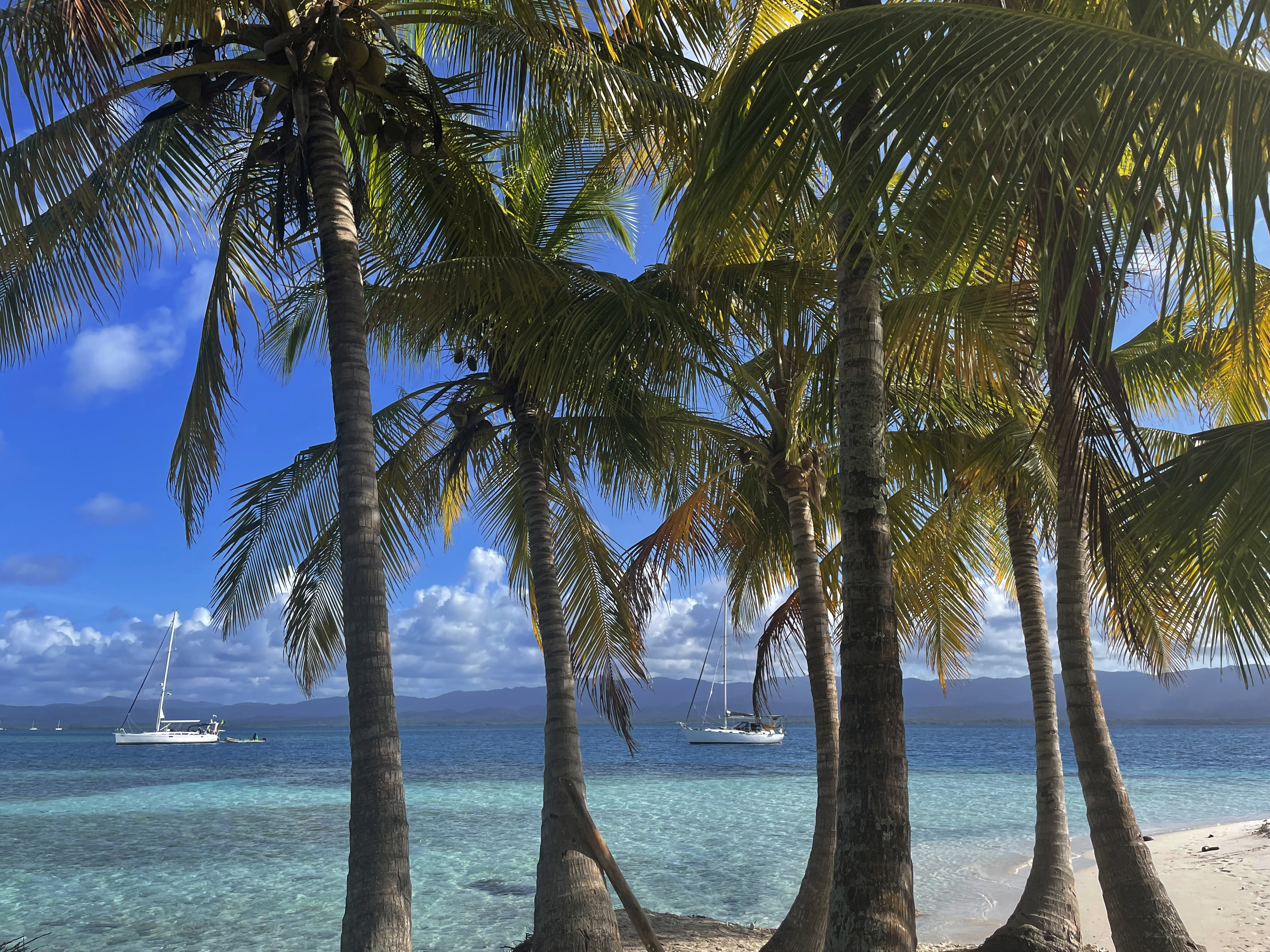

SEEING THE SUNRISE

Sailing the San Blas, I didn't want to miss sunrise. The first rays of light turned the clouds pink, then caught on the swaying palm trees before illuminating the sea in shades of blue. As the sun moved higher in the sky, the color of the sea would morph from a deep azure to the kind of pinch-me-I'm-dreaming turquoise that makes you want to jump in immediately. And the waters were calm because of the protective barrier reef encircling the islands. From our anchorage in the Cayos Holandeses (Dutch Cays) at the northern edge of the archipelago, we could see the powerful Caribbean waves crashing in plumes of surf against the reef.

Because the lack of a keel on the catamaran results in a shallower draft, our boat could anchor closer to the islands than the handful of monohull sailboats we encountered at an anchorage. It was an easy swim or paddle to individual cays. Occasionally, as we'd walk along a beach, we'd stumble upon plastic blighting the landscape. Whether washed ashore from ships, carried by tourists or consumed by the Guna, plastic is increasingly a problem. (There's no infrastructure in place to collect trash, and what can't be composted or fed to the fish is burned.)

A bigger problem is rising seas due to climate change. In "The Panama Cruising Guide," the bible for sailors navigating these waters, Eric Bauhaus writes: "Every time I do a survey ... I have to take islands off the maps that are now nothing but shoals."

Keen to show us the best snorkeling spot, Fred sailed the Zenith to a place called the "Sand Islet," so named because of its lack of trees. What used to be a cay is now a spit of sand encircled by a coral reef. Over time, Fred has seen hermit crabs fighting over an increasingly shrinking territory until it was nearly covered by the Caribbean. We snorkeled for more than an hour with Marina, who pointed out sculptural coral as mesmerizing as the fish. The starfish glowed orange, and dolphins frolicked in the waves next to us. We were so enthralled by the vibrant underwater world that we didn't notice how far we had drifted in the currents. Fred picked us up in the dinghy and carefully motored to the disappearing cay, where we sank our toes in the sand that would soon be completely submerged.

"The water is rising more and more every year," Chemier later told me. "In about 50 years, the Guna people will have moved onto the mainland because of the submersion of their islands. This is a destination to be seen quickly before it disappears."