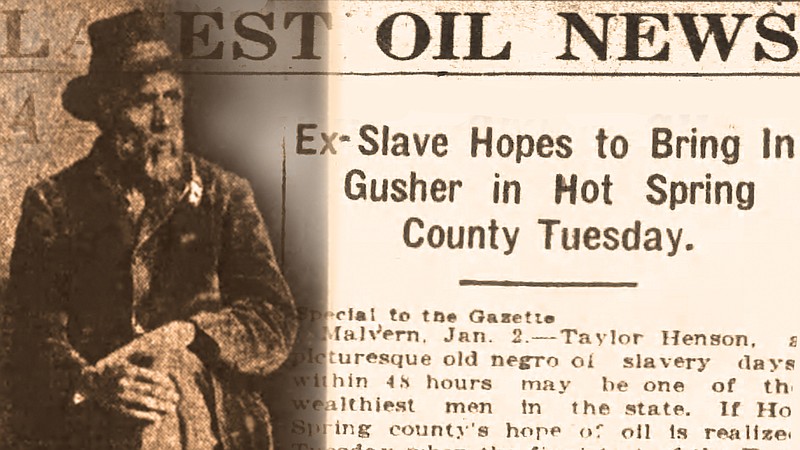

Taylor Henson had a dream of producing oil on his land near Malvern, an area not known to have petroleum reserves. In the final years of his life, Henson made a concerted effort to finish a well he had started earlier — but he faced many obstacles, including sabotage and arson. In 1922 Henson set off a mini-oil boom, with mineral rights being sold left and right, and three wells being drilled in Hot Spring County.

Who was this aging man who had once been enslaved?

Very little documentation exists on Henson's life prior to his fame as an oil driller. He was born to enslaved parents, Ozie and Anna Henson near Tulip in what is today Dallas County, probably in 1850. Tulip was an important settlement, most notably being home to two prominent educational institutions — the Arkansas Military Institute and the Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary. (Contrary to popular belief, Tulip was never considered for the state capital.)

Taylor Henson was owned by Washington Henson. In 1850, Smith Township, where Tulip is situated, had an enslaved population of 996 people. Among the white population, which stood at 700, were 11 plantation owners with more than 20 slaves each.

Another of those slave owners was Dr. Sanford Reamey, the owner and father of Scipio Africanus Jones, who would become the most prominent Black lawyer in Arkansas history.

Tulip faded away after the Civil War. Both the military institute and the girls' school closed during the hostilities and never reopened. Large numbers of residents — Black freedmen and white people — left Tulip after the war, many of them moving to the new railroad town of Malvern, a few miles to the north. Among the freedmen was Taylor Henson.

According to a feature article on Henson in the May 1917 issue of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, "The Man Who Never Sold an Acre," he initially rented 10 acres of farmland in the Ouachita River bottoms, on which he planted in corn.

Unfortunately, the river washed away his crop as well as those of other freedmen. Henson and the others replanted their crops — which grew well until a drought stopped all growth. Most of Henson's neighbors gave up on farming and moved to Malvern and other towns, but he carefully husbanded his crop, creating a mulch of tilled soil to slow the loss of ground moisture.

[Gallery not showing? Click here to see photos: arkansasonline.com/59oil/]

At this point, the young Henson demonstrated his business sense by not only harvesting his own corn, but by cutting his neighbor's abandoned and stunted corn plants for animal fodder. He cleared only $100 that first year, but he was not discouraged. He realized that renting land was no way to become established as an independent farmer, and he resolved to free himself from the "furnish merchants," who charged high prices to finance crops.

By February 1873, Henson was successful enough to marry Frances Jones, about whom little is known. They became the parents of seven children, though only four were still living in 1900, according to the U.S. Census.

OWNERSHIP

Henson resolved to buy his own land. This impulse to own land would become a part of Henson's identity and his claim to economic success.

He took advantage of a sheriff's auction of foreclosed land to buy 40 rich acres for $600. As the Crisis article suggests, Henson "was obsessed by the idea of buying land." Eventually he would come to own more than 1,000 acres.

In addition, newspapers reported that Henson acquired mineral rights on about 4,000 acres. One should not forget here that Henson had not one day of schooling and was illiterate.

Henson did sell land occasionally, including the site for the Acme Brick Co. plant in Perla, on the northeast outskirts of Malvern. Tradition has it that Henson extracted a pledge from the buyer to open jobs to Black workers. He also sold land from which the clay was used to make the bricks — land still being mined to this day.

THE COTTON TRAP

Hard work helped Henson survive, but much of the credit must go to his decision to plant food crops rather than cotton as did so many other Arkansas farmers.

Given his inability to read, Henson must have instinctively realized that it was unwise to get caught up in the cotton economy — a trap that put farmers at the mercy of the international cotton market. For 30 years after the Civil War, cotton prices were basically flat, with prices falling to 9.4 cents per pound in 1888.

A feature on Henson in the January 1922 Arkansas Gazette noted: "When the white farmers of this community were raising cotton and corn, Taylor was growing the finest of sweet potatoes in abundance and his luscious watermelons and cantaloupes were famed for miles around."

In 1899, Henson and a nearby white farmer named Jack Clift shipped more than 9,000 bushel baskets of cantaloupes alone. Shipments increased later when Henson persuaded the railroad to build a loading dock next to his farm and to provide special rail cars that would cushion his perishable produce.

No doubt much of Henson's financial success was due to his frugality. Even in old age, when he was financially secure, Henson would not allow a news reporter to take his picture — until he was told it would cost him nothing.

CIVIC DUTY

Given his heavy work schedule, it is remarkable that Henson found time for politics.

After Black Arkansans were effectively disfranchised in the 1890s, many of them and poor whites stopped voting altogether. We do not know when he began his work within the Republican Party, but in 1900, newspapers reported that Henson was elected to the Hot Spring County GOP convention.

Six years later, he was one of four Black delegates to the county convention. In April 1908, he was one of four county delegates to the 6th Congressional District Republican convention.

HIS OIL WELL

While Henson might have been well known in Malvern, in November 1919 he became front page news throughout the state and region when his search for oil began to look successful.

We do not know exactly when he began drilling the well; one newspaper reported he had been intermittently working on it for 20 years. As with buying land, Henson became obsessed with his oil well, maintaining his faith in the well even when drilling rigs failed and saboteurs did their best to destroy the well.

While we don't know how long Henson sought to find oil, we do know the day that workers who were busily bailing out water found their pails filled with oil.

The Arkansas Democrat ran a stringer's report Nov. 1, 1919, headlined "Oil reported near Malvern." The brief article, datelined Malvern, mentioned that the Taylor Henson Oil and Gas Co. "has brought in a well ... two and one-half miles north of this city."

Over the next two months newspaper articles reported on Henson's well, the reporters often allowing their enthusiasm to get the best of their judgment. It is no wonder that an oil boom resulted.

Arkansans were eager to cash in on the petroleum industry. And, just as happened about one year later in El Dorado when oil was discovered there, Malvern filled up with men anxious to get in on the boom.

As early as December 1919, only a month after the Henson well was reported to have struck oil, an unidentified speculator advertised in the Democrat that "I have a few oil and gas leases for sale; close in to Taylor Henson's oil well at Malvern." After assuring readers that "the well is well down in the sand with a fine showing," he asked interested buyers to "see me at Hotel Marion, room 625."

That was just the beginning.

EXCITEMENT AT MALVERN

Even after news reports were published in June 1921 clarifying that "rumors of [oil] flow are premature," speculators continued flooding into Malvern. In February 1922, the Gazette published an account of the oil boom's impact on Malvern, noting: "More oil scouts and representatives of oil corporations were here today than on any other day."

The Malvern Chamber of Commerce had to hire extra staff to deal with a vast number of inquiries received daily by mail and telegrams. The local telephone company brought in additional operators from Little Rock.

Investors from Springfield, Mo., organized a new company, the Mosier Oil & Gas Co., to drill a well "not far from the Taylor Henson [well], near Perla." While it is unclear whether the new company actually commenced drilling, by the advent of 1922, drilling was underway at three other locations near Malvern in addition to Henson's.

Though Malvern was a robust railroad town of 3,864 people in 1920, it did not have lodging sufficient to house the new arrivals. "Hotels are crowded," the Gazette reported, "and many homes are being opened to take care of many who have come to the scene in their cars."

The newspaper also expressed surprise that "leases continued to climb in price" despite Henson's inability to "bring in" his well.

DRILLING SITE DAMAGED

As the Democrat reported, Henson persevered through "every obstacle and misfortune imaginable" in his Ahab-like determination to complete his oil well.

The Democrat also reported what was well known in Malvern--"some evil-minded persons" had sabotaged Henson's well by dropping a railroad rail into the well. Henson had to devise special equipment to extract the rail-- which had been modified to make it difficult to withdraw.

Henson's drillers made enough progress by mid-January 1922 to plan a test of the well in a few days. However, only two days before the test, the concrete casing at the bottom of the well collapsed, necessitating another 10-day delay. The Gazette noted that "many oil men from El Dorado, Haynesville and Hot Springs stayed all day at the well."

Henson did not live to see his well through to the disappointing end. In mid-February 1922, about 72 years old, he fell ill and was soon bedridden, diagnosed with pneumonia at first. One news account stated that Henson lost consciousness.

A private firm, Lily & Nelms of El Dorado, was hired to complete the well.

Henson was still bedridden on Feb. 23, 1922, when he learned that bailing of water from the well had brought up oil. In addition to oil in the bailer, according to the Democrat, "there is oil in the slush pit, and oil is spread pretty much all over the derrick floor and the surrounding topography for some distance."

LEGAL SABOTAGE

The hole stood at a depth of 1,300 feet. More excited reports were published the next day, including a statement by Texas and Louisiana oil men that "the old Negro owner of the property has a 'real oil well.'" Still, the Democrat story reported another stoppage — this time to "clarify title" to the land.

Henson was well enough by March 5 to file suit to cancel a contract with the firm he had hired to complete his well and exploit his other leases.

All work at the well stopped. "The Henson well seems to be hopelessly involved in [a] legal tangle," the Gazette reported. Actually, Henson was no stranger in the courts as he often sued railroads for injuring his livestock, among other contentions.

ARSONISTS STRIKE TWICE

At this point, with his hopes crumbling around him, Henson's home was set afire by arsonists. Details of the fire are unknown, but the Malvern Fire Department saved his home — though it was outside the city limits.

"We have to look out after Taylor," commented the head of the Malvern Chamber of Commerce. The words must have seemed hollow to Henson since his new home was soon burned again by an incendiary — and this time everything was a total loss.

On June 10, 1922, Henson's drilling operation resumed, with new equipment used to set casings in the well.

However, Henson died less than 10 days later, on June 19. He was buried at Perla cemetery. In reporting his death, the Hot Spring Sentinel Record noted that Henson died after being confined for months and that "he invested much money in the oil movement of the county."

Henson family members retained the land for the rest of the 20th century and the first two decades of the 21st, only selling it two years ago.

The 1922 oil rush continued for a short time after Henson's death, but interest dwindled as it became clear that none of the wells being drilled in Hot Spring County produced meaningful amounts of oil.

Tom Dillard is a historian and retired archivist living in rural Hot Spring County. Email him at

Arktopia.td@gmail.com

Gallery: Taylor Henson strikes oil