« 1860 »

In November 1860, newly elected Arkansas Gov. Henry M. Rector learned just hours before he delivered his first speech to the General Assembly that Abraham Lincoln had been elected U.S. president. Rector wanted Arkansas to secede from the Union at once.

Republicans Lincoln and his running mate Hannibal Hamlin had not called for the abolition of slavery, but they did advocate banning it from territories. That would prevent the admission of new slave-holding states.

There was no Republican Party in Arkansas; the state had given all four of its electoral votes to Southern Democrats John C. Breckenridge and Joseph Lane, who urged slave states to secede should federal laws permitting slavery change. The popular vote was 20,732 for Breckinridge and Lane to 20,094 for the conservative Conditional Unionist ticket, John Bell and Edward Everett, who said the Constitution protected slavery and they would have no trouble defending it.

Bringing up the rear in Arkansas were Democrats Stephen A. Douglas and Herschel Johnson, who wanted to let the territories decide for themselves.

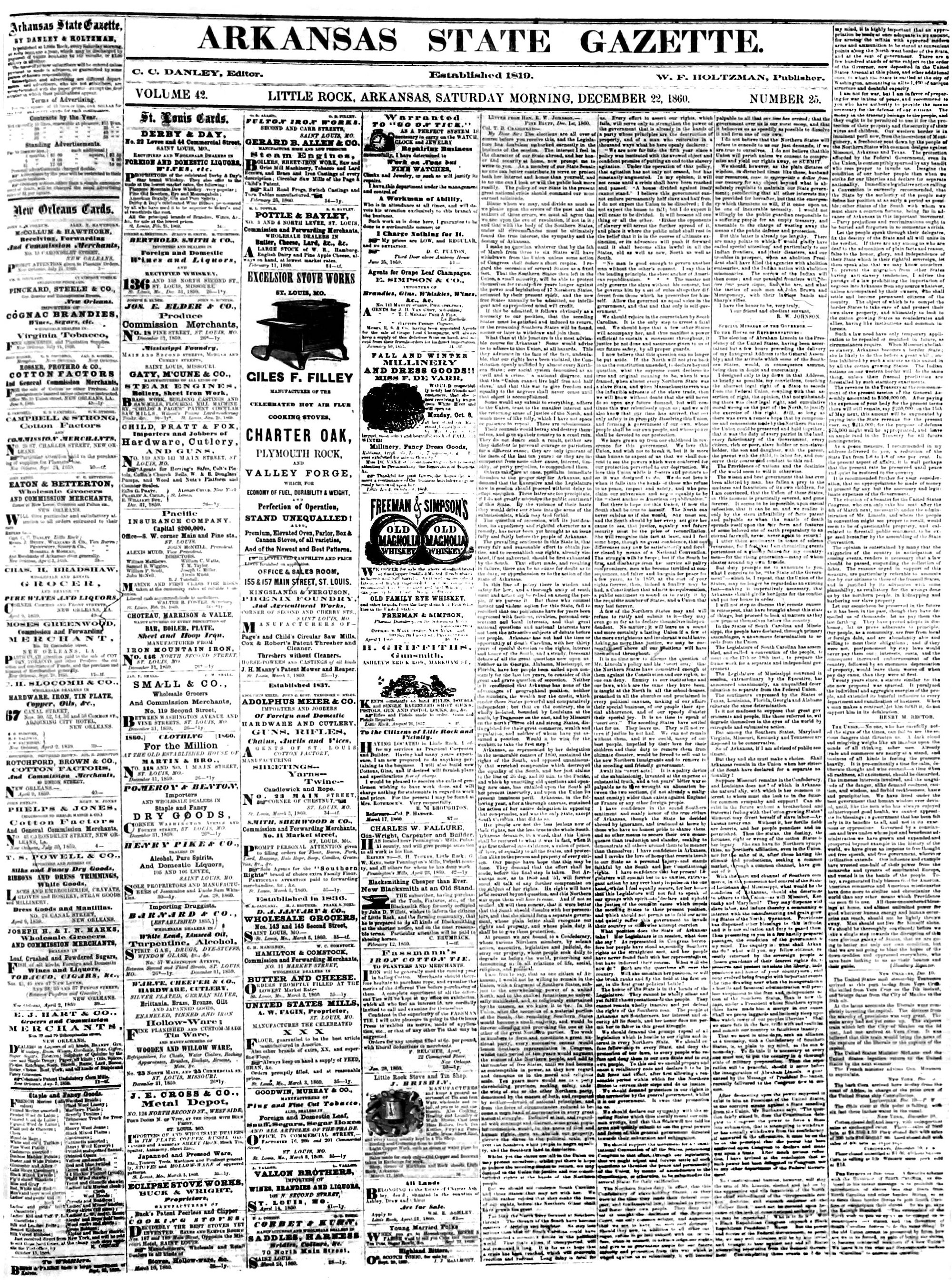

Page 1 of the Dec. 22, 1860, Arkansas State Gazette contains Rector’s second address advising legislators that it’s too late to wait to see what the “radical” new administration might do. The state must join in a Confederacy of Southern States or it won’t have any trading partners.

Gazette historian Margaret Ross calls November and December 1860 editor Gazette Christopher Columbus Danley’s “finest hour” — not because he liked Lincoln, but because he saw no reason to rush into secession. In print, he called for patience and faith in justice, and in private he lined up Conditional Unionist candidates to run as delegates for any secession convention should the “fanatics and fools” in the Legislature vote to hold one.

— Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.