« 1891 »

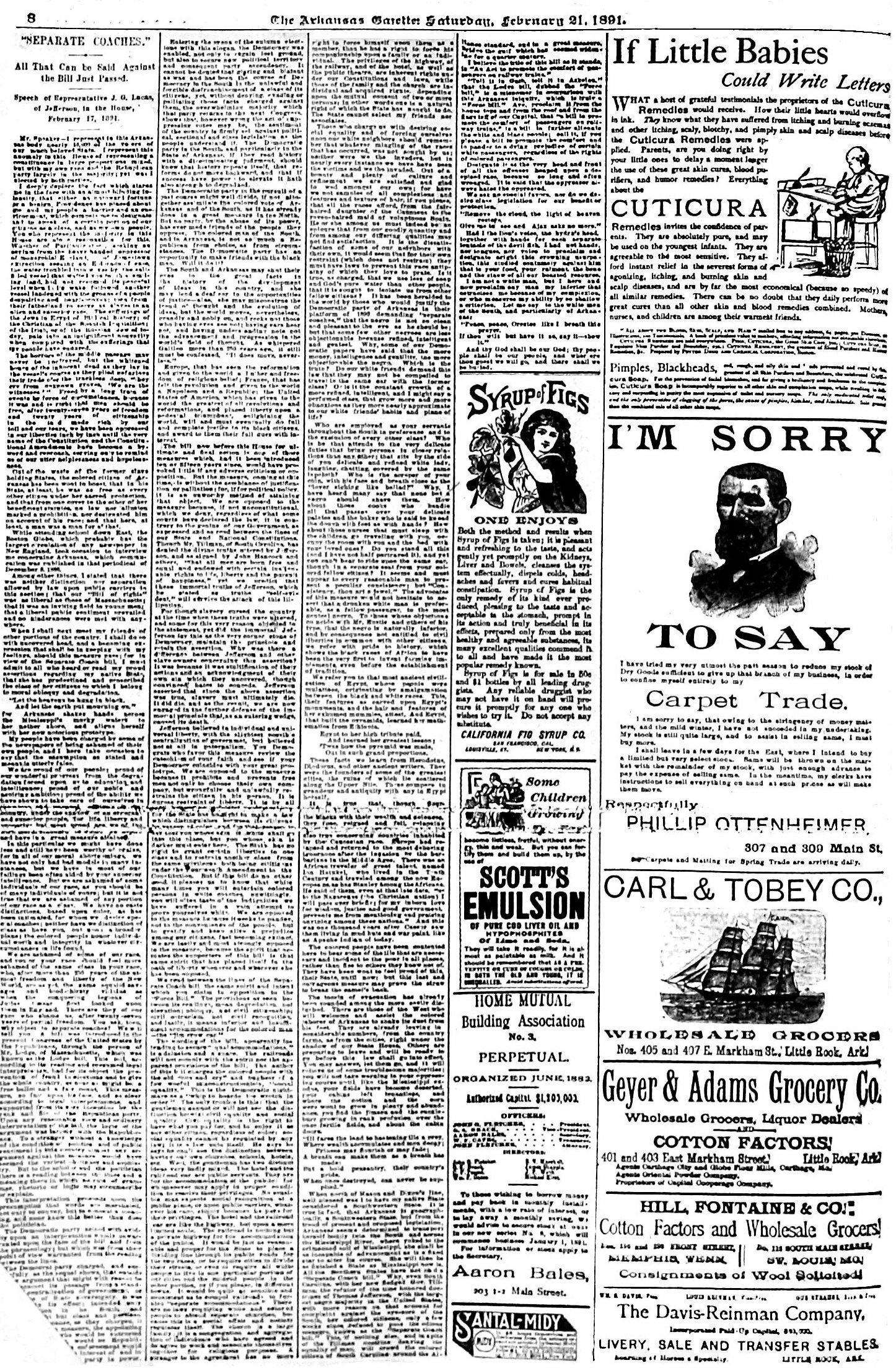

State Rep. John Gray Lucas was one of a dozen black men serving in the 28th General Assembly when it passed the Separate Coaches bill, the first of Arkansas’ Jim Crow laws. Enacted across the South from the end of Reconstruction through the early 20th century, these state and local laws mandated racial segregation and denied black citizens their civil rights.

The Separate Coaches bill required railroads to provide different “but sufficient” passenger cars for white and black riders.

As his colleague Sen. George W. Bell of Desha County did in the Senate, Lucas rose in the House to argue against the bill. The Arkansas Gazette published his speech Feb. 21, 1891, on Page 8.

Lucas did not pussyfoot around. By turns poetic, coolly intellectual and scornfully direct, he ripped the pretense that separate facilities were for black citizens’ benefit. He warned that if their rights were not respected, black citizens would desert the state. And, he insisted, that would betray the founding principles of the Democratic Party and cripple the state’s economy.

“We are opposed to the measure because it prohibits and prevents free men not only to choose their own company, but wrongfully and unlawfully restrains the citizen in his person,” he argued.

Born in Texas, Lucas grew up in Pine Bluff and attended public schools. In 1887, he graduated from Boston University’s School of Law and was admitted to the Arkansas bar. Soon he was appointed assistant prosecuting attorney for Pine Bluff and then U.S. commissioner for the state’s Eastern Judicial District. At 27, he was very active in the Republican Party.

But Democrats controlled every level of government after the 1890 election. In an article for the Arkansas Law Review,“(Extra)ordinary Men: African-American Lawyers and Civil Rights in Arkansas Before 1950,” Judith Kirkpatrick explains that the party shored up its thinning ranks by making promises to racist farmers who were threatening to join splinter parties devoted to agrarian causes.

Six hundred black citizens in Little Rock held a protest meeting and passed resolutions. Four hundred came to a protest in the Chamber of the House, with forceful speeches. All but one of the 12 black legislators voted against the bill.

It passed anyway.

Lucas said goodbye to the state he had proudly recommended as a land of opportunity. He moved to Chicago and built a respected practice, with white and black clients. He argued before the U.S. Supreme Court four times. He was known in Chicago’s black press as a “black millionaire.”

— Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.