« 1910 »

Arkansans caught comet fever in 1910, the year astronomers predicted the return of Halley’s comet.

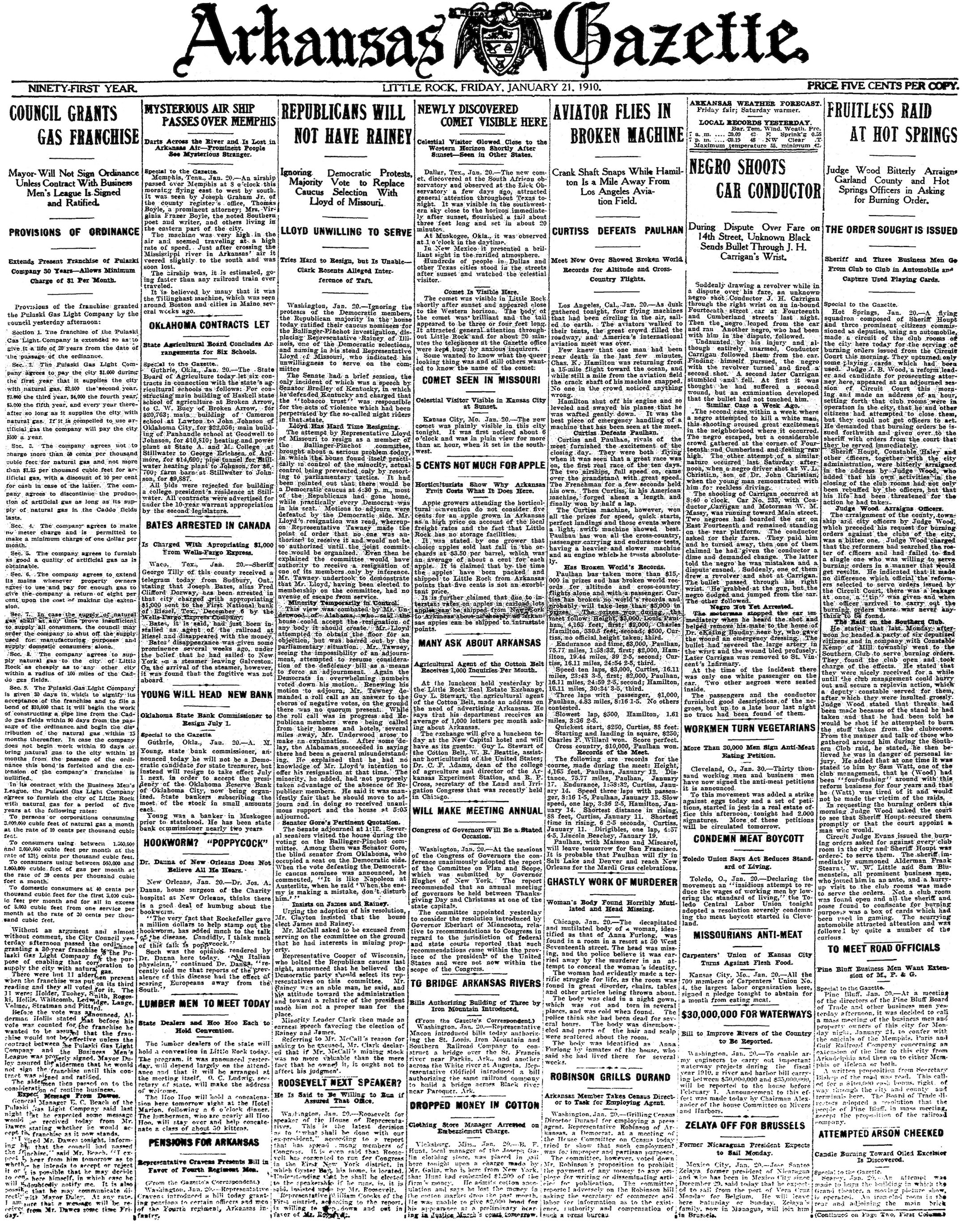

On Page 1, Jan. 21, the Arkansas Gazette reported that a brilliant comet had appeared above Little Rock shortly after sunset the day before. The tail looked from the ground to be 3 or 4 feet long, and it blazed such a long time that the phone rang in the newspaper office for 20 minutes. Was it Halley’s?

Over ensuing days, reports explained that “the interloper” of “appalling” brightness was a new comet christened A-1910. Experts remarked on its similarities to another comet, the Great Comet of 1882; but it was “evidently” not the comet named for astronomer Edmond Halley (which rhymed with “valley”), which was coming but from another direction and was not yet visible.

The Gazette published more than 200 comet-related items in 1910. It regaled readers with expert explanations and not-so-expert notions about Halley’s, which passes near Earth once every 75 years. A few days before A-1910 appeared, the paper gleefully quoted a magazine devoted to “occultism and evolution” as predicting that — at about 6 p.m. Greenwich time May 18 — Halley’s would produce “‘a national shame’ and … some shameful, heartless, despicable action by a government is to be expected and a cruel, vicious and degrading warfare might be the result.”

Astronomers reassured the masses that, while the comet’s tail was expected to sweep the planet, possibly electrifying the atmosphere, that wouldn’t hurt.

The first Arkansan to spot the returning Halley’s was Professor J.T. Buchholz, who on Feb. 4 happened to aim his 2-inch telescope at what he expected to be blank space while instructing student teachers at the Arkansas State Normal School in Conway.

Soon Halley’s sightings — via telescope — were published from all over, as well as poems and other merriment. It wasn’t until mid-May that Arkansans saw the comet with bare eyes, if they got up in the wee hours. Interesting things happened to early risers: A man in Benton discovered that his church was on fire. A father in Pennsylvania caught his daughter trying to elope.

Before Halley’s faded, comet fever was eclipsed by a more somber watch party: The great American observer Samuel Clemens — Mark Twain — had been laid low by painful angina and grief over the death of his daughter. When he took to his bed, the Gazette updated readers daily.

Twain had joked that, having been born in 1835 with Halley’s comet overhead, he expected to go out with it in 1910. Which he did, on April 21, 1910.

— Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.