« 1916 »

“Readiness” was the word in 1916. The Great War in Europe had spilled into the oceans, and although the United States stood pat on its official neutrality, support for Germany went down with the Lusitania. Interest in paramilitary clubs like the Boy Scouts sprang up, and retailers and editorial writers warned the public to be prepared.

But the call, when it came, was not to fight Germans.

North America had its own conflict — six years of civil war in Mexico sparked when that nation’s 80-year-old president Porfirio Diaz rigged an election to avoid stepping aside. Replacement governments failed in a whiplash of factionalism with assassins, revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries.

The United States favored first one side and then another. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson shifted support to Venustiano Carranza, head of a pro-constitution government. A Carranza rival, Gen. Pancho Villa, attacked a trainload of Americans inside Chihuahua and then crossed the border to plunder and burn Columbus, N.M.

Wilson sent Army Brig. Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing and 11,000 regular soldiers on a (futile) mission to catch Villa, leaving their border posts empty. Since 1903, the Dick Act allowed states’ Guard units to fill in for the regular Army; in 1916, the National Defense Act gave the president the right to federalize them — to borrow them from the states. On June 18, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker used this power to call up the National Guard of the United States.

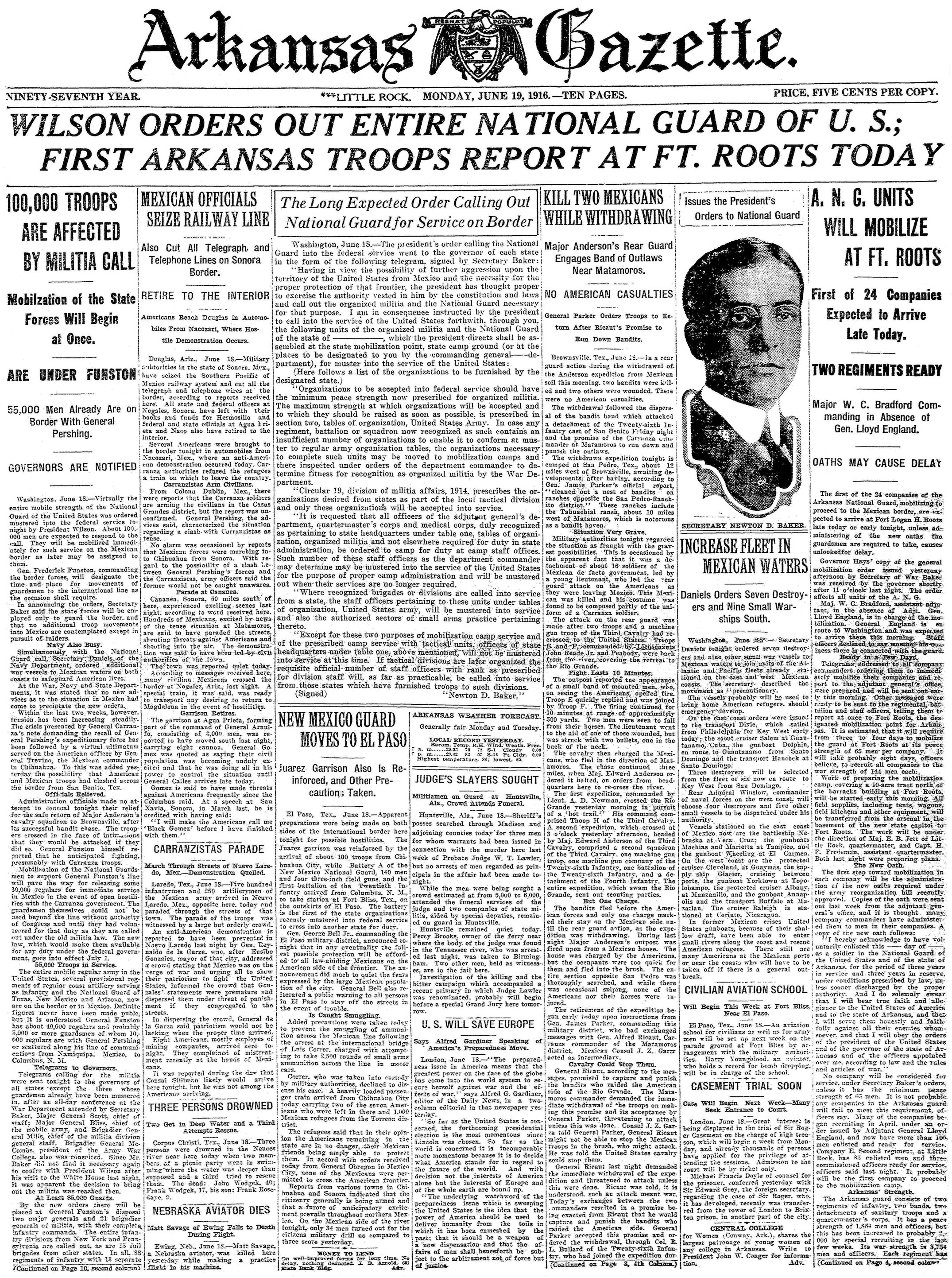

Page 1 of the June 19, 1916, Arkansas Gazette broke the news that all Guardsmen were to report to Fort Roots above Argenta (North Little Rock). Baker’s letter to governors led the page, including the blank left for the name of a state.

Arkansas mustered two regiments. After eight hectic weeks of drilling with small arms, about 1,300 “boys” left by train for Deming, N.M., and a seven-month, eye-opening, tedious — but unsafe — introduction to war. They found camaraderie, new scenery, odd lizards and, unlike home, which had outlawed alcohol, saloons.

The Arkansans did not see combat, but there were deaths. One soldier died when a supply sergeant accidentally triggered a Lewis machine gun; another drank poison whiskey sent to him as a Christmas gift. One man froze to death; others died of pneumonia — six died of measles complicated by malaria and pneumonia. And there were desertions: One man slipped away to stop his first wife from exposing him as a bigamist to his war bride. He failed.

The regiments returned to Arkansas in February and March 1917 and were greeted as heroes.

— Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.