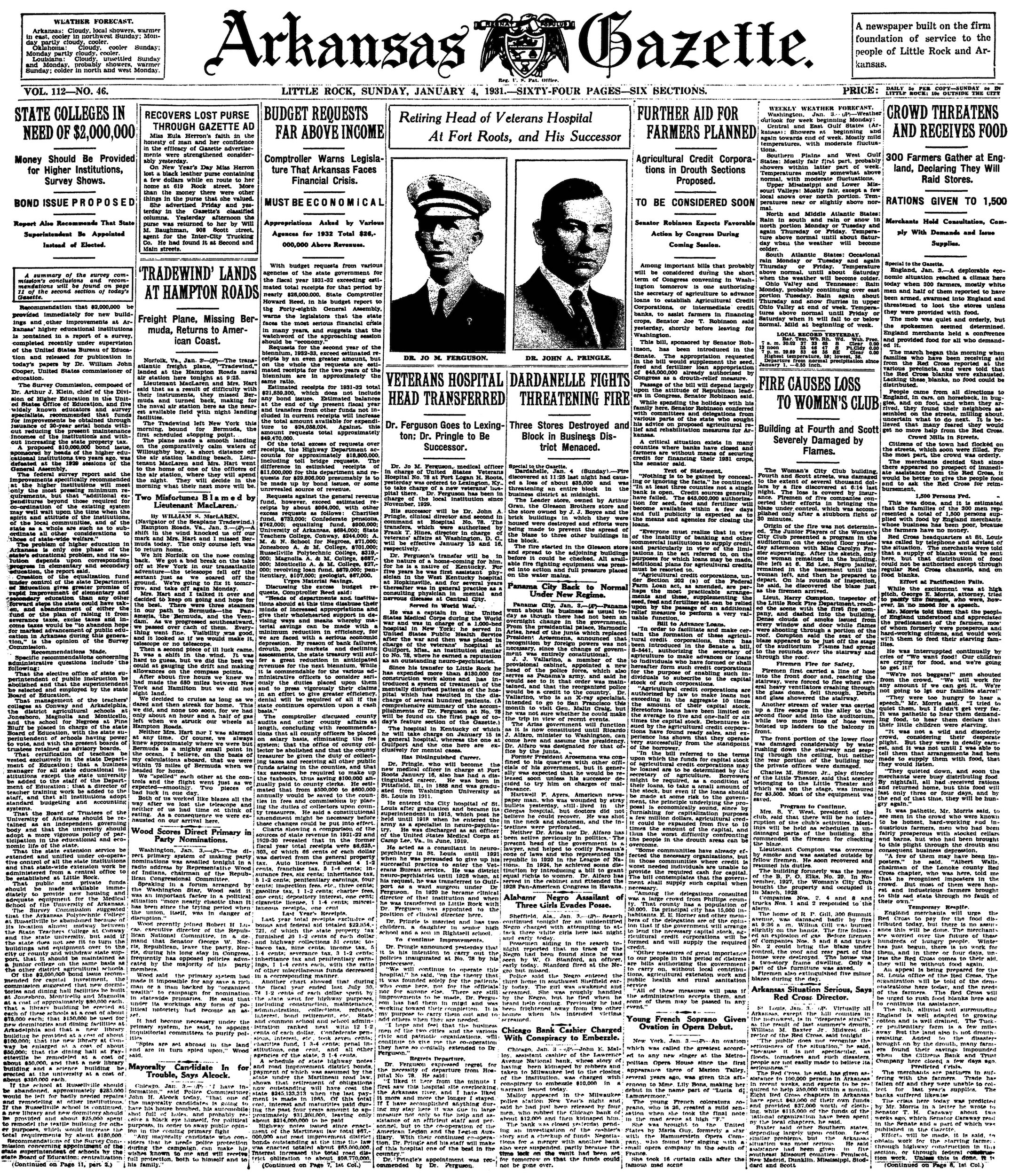

« 1931 »

On Jan. 4, 1931, in the seventh month of a devastating drought, the front page of the Arkansas Gazette reported on an incident at England in Lonoke County.

Three hundred men, mostly white, had marched from the Red Cross relief station to surround stores and demand food. They were well-behaved, but half were armed, and they did threaten to take food if they weren’t given some. “We’re not going to let our families starve!” one yelled.

Albert Walls of Lonoke, chairman of the local Red Cross, told a Gazette stringer that the station had exhausted its supply of the requisition blanks used to order food from local merchants. These invoices were the record of what the Red Cross at St. Louis owed the merchants. Without blanks, no food could be distributed.

The station, one of 29 in Arkansas, had run out before. It was feeding hundreds of sharecropping tenant farmers, unemployed field hands and stranded “drifters” who had arrived to pick crops that died in the drought. Added to the disaster, many farmers found their savings impounded when the Citizens Bank and Trust Co. closed.

In an article published in the Arkansas Historical Quarterly in 1970, “Hoover and the Red Cross in the Arkansas Drought of 1930,” Roger Lambert explains that the merchants conferred with the Red Cross, which promised to reimburse them. With hastily prepared requisitions, merchants supplied $1,500 worth of staples.

And this was the so-called England Food Riot, which made national headlines.

Pushed by Arkansas’ Democratic Sens. Thaddeus Caraway and Joe T. Robinson, the Senate had passed a $60 million package of farm loans for drought relief in December 1930. But the Republican-led House cut the amount, along with the word “food” from the list of allowed uses. In his biography of Caraway published by the Arkansas Historical Quarterly in 2005, Cal Ledbetter explains that a joint conference committee restored the appropriation to $45 million for feed, seed and fertilizer, but retained the food exclusion.

Two days after the “riot,” Caraway invoked it while introducing a bill to provide $15 million in loans for drought-stricken farmers to buy food. The Senate passed the bill at once, but it died in the House. Robinson then amended the Department of the Interior appropriation, adding $25 million for the Red Cross, to supply food. This also passed the Senate but failed in the House.

The stalemate was broken by Harvey Couch, Arkansas utility executive and chair of the state Drought Relief Committee. He arranged a compromise that added $20 million to the $45 million seed, feed and fertilizer bill with the understanding the money could be used for loans to buy food — but without putting that in words. More than $3 million found its way to Arkansas.

On Oct. 29, 1931, Caraway entered St. Vincent’s Infirmary with a kidney stone. Eight days later, he died of a blood clot in a coronary artery. He was 60.

Gov. Harvey Parnell appointed his widow, the now-famous Sen. Hattie Caraway, to fill out his unexpired term. She was expected to step aside when it ended in March 1933. She didn’t.

— Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.