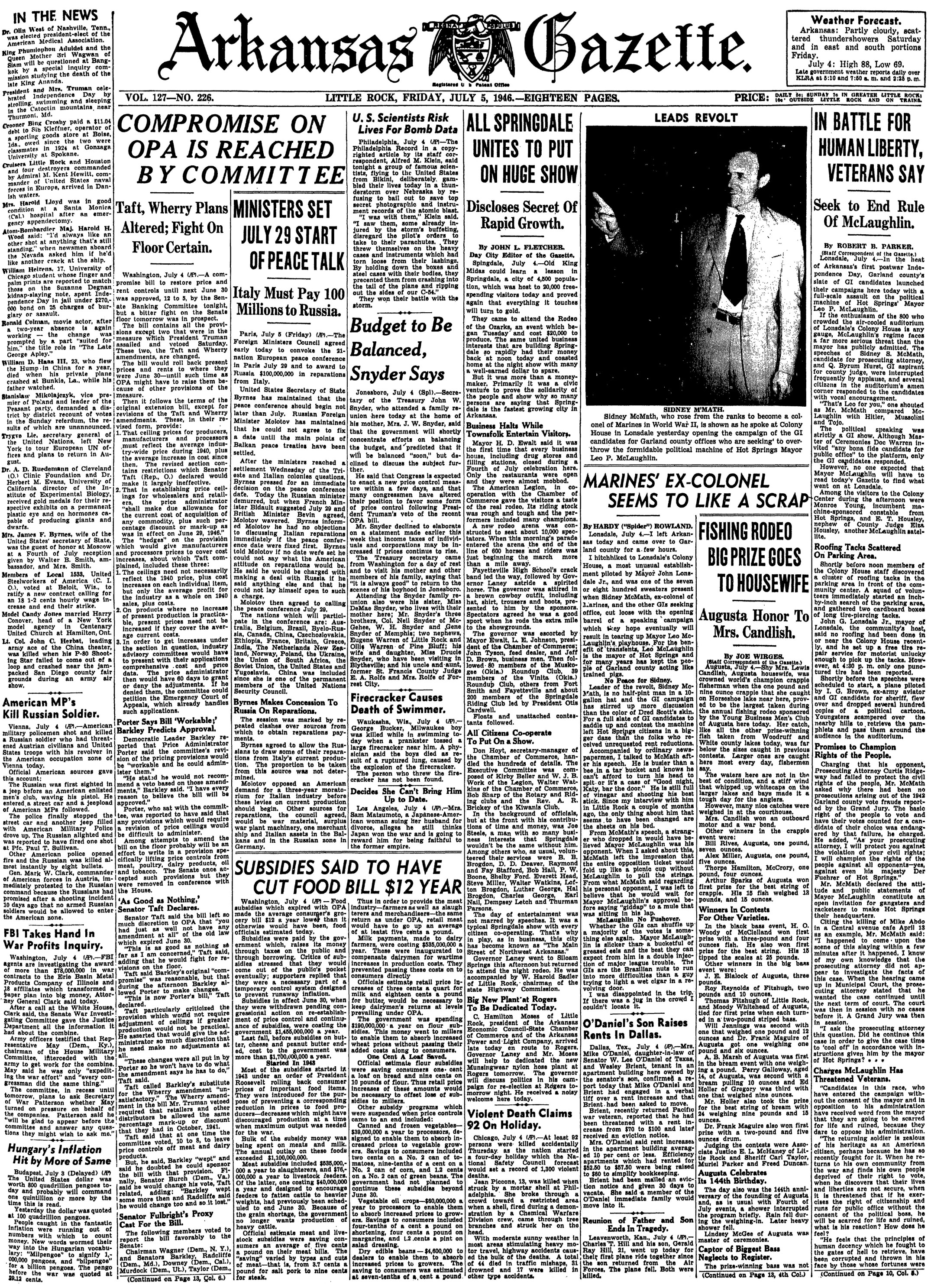

« 1946 »

Page 1 of the July 5, 1946, Arkansas Gazette reported on an ongoing rebellion by young(er) Democrats against a state party ruled by entrenched officeholders more interested in racial segregation than progress. This reform-minded Government Improvement League, soon nicknamed the GI Revolt and associated with war veterans, inspired little political insurrections around the state as citizens who wanted a crack at public office stood up against county overlords, some in place since the Roaring ’20s.

Arkansas had some free-range Republicans, live ones, but it was by and large a one-party state and had been since the Brooks-Baxter War. As historian Michael Dougan has put it, issues were of little importance compared to personalities, and rigged elections were a way of life in counties managed by machines.

According to the Central Arkansas Library System Encyclopedia of Arkansas, GI League members stood for office in Pine Bluff and in Cleveland, Crittenden, Garland, Montgomery, Pope and Yell counties. Most county machines were ant farms compared to the glitzy operation of Mayor Leo P. McLaughlin in Garland County. As the Gazette’s memorably cranky political analyst Hardy “Spider” Rowland cracked on this page, “I left Arkansas today and came over to Garland County for a few hours.”

McLaughlin ruled for two decades, coddling mobsters, sending pink notes home with public employees to inform their families how to vote — getting out that cemetery vote and manipulating poll tax receipts — and feathering his nest through an old-fashioned licensing system in which pimps and prostitutes paid for protection.

Good-looking reformers epitomized by Marine hero (and future governor) Col. Sidney McMath of Hot Springs waged what Gazette city editor John L. Fletcher christened “the Battle of Hot Springs” to break McLaughlin’s stranglehold. They proved in court that poll tax receipts were mishandled. They filed for office against machine candidates on the county level and for circuit judge and prosecuting attorney. None of them won in the party primary — except McMath. When frustrated reformers started bolting from the party to run as independents, the old-line embraced McMath to lure them back.

In Community Voices, his history of the Arkansas Press Association, Dougan observes that McMath is the figure most often associated with the GI Revolt, but he was not alone. Another was (future governor) Maj. Orval Faubus of Madison County, who had been circuit clerk and recorder before he left for the war. When he tried to retake his post in 1946, he was defeated by the incumbent, oddly enough a Republican. Faubus became postmaster at Huntsville, acquired the Madison County Record and used it to promote Sid McMath.

— Celia Storey

You can download a PDF by clicking the image, or by clicking here.