One hundred years ago, Arkansans gaped as a bright star of delightful silent movies was accused of a crime so vile it was pretty much impossible to describe in print. And yet the newspapers managed.

His name was Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle, and he was deemed not guilty of crushing a starlet's bladder during a rape at a drunken orgy in a San Francisco hotel. But in Arkansas newspapers published in September 1921, he sure looked guilty.

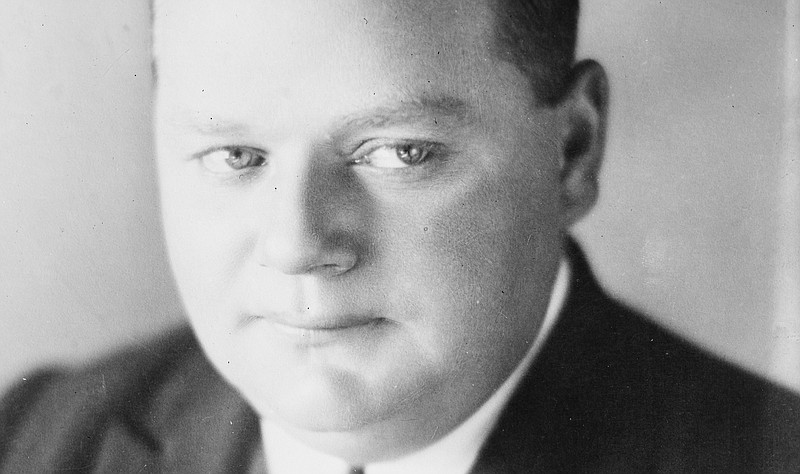

Friend Reader probably knows the story of "Fatty" Arbuckle (1887-1933) better than I do, but due diligence requires me always to pretend that readers know very little. So, here are some basics gleaned from accounts in the Arkansas Democrat and Arkansas Gazette, a bio of the actor at IMDb and a history piece I quite like, which was written by Gerald King for Smithsonian Magazine and posted online Nov. 8, 2011 (see that at arkansasonline.com/913fatty).

BELOVED FILM CLOWN

The talented and charming Arbuckle was said to have weighed 13 pounds at birth. He was one of nine children born to a Kansas couple who moved to California when he was 2. By age 8 he was a stage performer.

According to IMDb, by 20 he'd been an acrobat, clown, singer, director and had toured with a theater company that performed "The Mikado" in China and Japan. He worked for Mack Sennett's Keystone production studio, playing mostly policemen in one-reel comedies. He starred beside Charlie Chaplin, and had begun directing his own movies in 1914, making cute comedies with Mabel Normand (she was famous).

By 1917, he had a production company with Joseph M. Schenck and was earning more than $1,000 a week. He was the producer who hired the soon-to-be-great comic genius Buster Keaton.

Paramount Pictures paid Arbuckle $3 million to star in 18 silent films, and in 1921 he signed another million-dollar deal. "Crazy to Marry," his latest comedy, was playing everywhere that long-ago September, including in theaters at Little Rock.

Photo Gallery

Fatty Arbuckle in the news

In September 1921, the Arkansas Gazette closely followed news, rumors and gossip about accused murderer Fatty Arbuckle, who before Labor Day 1921 was a widely loved, famously well paid movie star.

[Photo gallery not showing up above? Click here » arkansasonline.com/920arbuckle/]

"So," as King explains in the Smithsonian article, "his friend Fred Fischbach planned a big party to celebrate, a three-day Labor Day bash at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco." But Arbuckle almost didn't attend because his buttocks had been burned earlier that week: He had sat on an acid-soaked rag at a garage where his car, a Pierce-Arrow, was being tended.

Fischbach found him a rubber pad to sit on for the drive up the California coast to the hotel, where he had booked adjoining rooms and a suite.

Among the random people who showed up for what papers termed "the booze party" was 25-year-old Virginia Rappe and an unreliable witness named Maude Delmont, who made a practice of blackmailing performers. Writing for Smithsonian, King says that when Arbuckle woke up on Labor Day and, still in his pajamas, bathrobe and slippers, saw those women, he told friends he wanted them to leave. He was worried their sleazy reputations would attract the police.

But there was liquor and music, and Arbuckle soon forgot his troubles, King writes. Four days later, Rappe died.

A Grand Jury indictment charged Arbuckle with manslaughter. But the supposed crime had occurred during the commission of a documented crime — the booze — so the prosecutor also charged him with first-degree murder.

In Little Rock, the Gazette was agog, picking up gossipy accounts daily from its national wire services, which were Hearst newspapers. Hearst reporters stuck to Hollywood's first great scandal like ticks on a hound, producing a confusing welter of hearsay accounts.

The Democrat, which got its domestic and national news from The Associated Press, published fewer and generally shorter stories, some reporting doubts about the veracity of Arbuckle's accusers. But he looked very, very bad in the Democrat, too.

Readers were treated to interviews with or stories about witnesses — actual, purported or missing — as well as industry gossips. One widely quoted supposed insider was across the county in New York when the supposed crime happened.

Witnesses came and went in the press, changing their tunes. Some of these people depicted the 266-pound actor and director as a sybaritic predator. Others said he was a very nice man and a faithful friend. His estranged wife flew to his defense and stood by him through his ordeal — which included three trials and the loss of his fortune.

Women's empowerment groups saw him as guilty and turned out for all the trials and to be quoted.

Rappe had been staying at the San Francisco home of director Henry Lehrman, who was in New York. He described her as a sweet young woman who "was never intoxicated in her life. She didn't like to drink. It made her sick. She was never promiscuous. ...

"For a year and a half I was Arbuckle's director. He is merely a beast. He made a boast to me that he had torn the clothing from a girl who sought to repulse his attentions and had violated her. That is what results from making idols and millionaires out of people that you take from the gutter. Arbuckle was a spittoon cleaner in a barroom when he came into the movies nine years ago. He was a bar boy — not a bartender — cleaning glasses and spittoons."

Lehrman explained that he had his information straight from Maude Delmont via telephone, and that this is what she said to him:

"After we got to the suite and had a few drinks, Arbuckle jumped up and seized Miss Rappe. He carried her into another room and locked the door. I heard her struggling and pounded on the door.

"They were in the room a quarter hour when we heard a terrific scream. I threatened to call the hotel office and he opened the door. I found Miss Rappe's clothing had been torn to shreds and that she was unconscious."

By Arbuckle's third trial, in April 1922, it was apparent that nothing of the sort had happened.

Rappe became ill at the party and Arbuckle and others got her a room and suggested she take a bath. They called in the hotel doctor who decided she was intoxicated and gave her morphine.

She had suffered from chronic urinary tract infections. She had peritonitis.

"But," King writes, "by the end of the week, Fatty Arbuckle was sitting in Cell No. 12 on 'felony row' at the San Francisco Hall of Justice, held without bail in the slaying of a 25-year-old actress named Virginia Rappe."

Behold this assessment of how Arbuckle handled his sudden fall from grace, published by the Democrat on Sept. 18, 1921. The unnamed wire service reporter paints a vivid portrait despite sounding like an awful cat:

"Arbuckle's appearance as he sat in Judge Harold Louderback's court room this morning had a touch of the suffering bovine. He is perhaps a more pathetic figure than a more nervous or mental type of man would be. His is not a philosophic suffering, but a stunned and troubled surprise. Despite his personal memory of a record that looks like experience it is probable that Arbuckle is not sophisticated at all. ...

"As he sat and listened to the formalities of his arraignment on the manslaughter charge, he resembled a child, too big to cry, who has stepped on one end of a board and been hit by the other end. 'Fatty' has done that very thing in pictures. Now he is doing it in life."

Friend Reader, I am grieved that I must pretend you don't know what happened next because this story is a long way from all told. But I am out of time. Let's pause for now, and I will finish pretending to enlighten you next week (Sept. 27).

Email:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com