Juvie: Lost Time, part II

Youth and officers at White River Juvenile Detention Center participate in mural painting, a gardening project and foster dog training as part of programs designed to help incarcerated kids improve. (Special to the Democrat-Gazette / JONATHAN PICKERING)

Youth miss out on school, mental services in lockups

BY AMANDA CLAIRE CURCIO / Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

Colton turned 17 alone in an unheated juvenile jail cell in Batesville, 370 miles from home.

He had only a thin mat and blanket for sleeping. Slugs crept in through a space between the wall and the ground. Water was turned off. Guards took his Bible, he said, but supplied a few squares of toilet paper when asked.

“I spent two weeks of that first month there,” Colton said. “Just sitting in a jumpsuit, freezing cold.”

The state of Arkansas then moved Colton to a state-run youth lockup in Harrisburg. There, he said, the on-duty staff sometimes slept at night, leaving youths free to attack one another.

When another teen inmate punched him in the face, Colton decided to run away. Police caught him the next day.

If anyone had asked why he ran, Colton said, he would have told them he was angry, afraid and beginning to feel hopeless.

He knew he had to stay out of trouble and meet prescribed goals before he could go home, but the goals required treatment, such as counseling or other supportive programs, which he didn’t get enough of behind bars. And the violence and abuse were a lot to take.

“I barely kept it together,” Colton said. “When you’re locked up with 100 different people who are angry just like you are, when you’re just trying to leave, there’s nothing you can do but get triggered.”

Colton’s not an isolated case, according to local youth advocates, watchdog inspection reports, other documents and interviews.

Jailed youths routinely spend weeks, sometimes months, without treatment for drug abuse problems or behavioral issues.

And state-run lockups, where young offenders serve their actual sentences, have too few therapists and education programs that fall short, watchdog reports show.

“Youth feel concerned that they are being held without any opportunity to complete the treatment which will lead to their release,” Disability Rights Arkansas wrote to state officials in 2017, after inspectors visited the state’s youthful-offender lockups.

At least one state facility violated federal law by limiting how many youths it classified as special education students, the nonprofit found.

Some critics also expressed concern about the state’s decision in 2017 to stop hiring certified teachers at its lockups and shift to virtual classroom teaching programs that use classroom “coaches” who are required to have only high school diplomas.

Routine shortages of social workers and therapists can delay services at state lockups, affecting how long a child must stay behind bars. For example, the ratio of social workers to youths — about 1 for every 20 kids — is too high, according to former lockup directors, who say a 1-to-12 ratio, or fewer, is ideal.

“The lack of therapists … has not only deprived youth of treatment, but created a dangerous situation at the facilities. … Staff without professional mental health expertise and support are attempting to defuse behaviors and are stressed by the lack of support,” Disability Rights’ letter asserted.

The nonprofit has federal authority to monitor the state’s lockups, and its inspection reports routinely outline a lack of counseling, therapy and education programs.

Pulaski County Circuit Judge Herbert Wright Jr. also has questioned whether the state’s juvenile facilities do enough to help kids.

In May 2017, Wright cited the state’s inability to rehabilitate youths when he refused to allow the transfer of a 15-year-old to juvenile court after the teen was charged as an adult for armed robbery.

“This Court hopes that all juvenile offenders may be rehabilitated,” his opinion reads. “But unless that system is provided with better resources, this will not happen.”

Wright declined to comment about the state’s promised changes to the juvenile justice system.

Youth sentences that are open-ended last far longer than the national average and add to the effect of inadequate services on incarcerated teens, community providers say.

“Kids come out of these facilities worse than they go in,” said Bonnie Boon, director of Consolidated Youth Services, a community-based program in Jonesboro. “The state needs to change how they give kids services.

“It seems nobody wants to talk about what’s really going on … the trauma these youths might have experienced there,” she said.

Division of Youth Services officials expect the level of treatment services to improve once its juvenile prisons are returned to private control this summer. The new contract calls for more spending on such services.

At the county level, Benton, Washington and Pulaski counties’ juvenile jails have created therapeutic sessions and other initiatives to help kids cope with their emotions, as part of a nationwide effort to reduce youth incarceration.

Jonathan Pickering, director of the White River Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Independence County since 2015, said he recently added several programs to help locked-up kids, including group and individual therapy sessions, foster dog training, mural painting and gardening projects.

“Our facility shouldn’t look like an adult jail,” Pickering said. “We need to create a less restrictive environment. Otherwise, it just creates more trauma for the kid.”

Also, a new state law aims to shorten sentences and divert more kids from detention into alternative programs so they can undergo treatment in their own communities.

Child advocates say they’ll wait and see what happens.

Benton County juvenile public defender Rita Smith said she worries that Arkansas’ efforts to overhaul the juvenile justice system — as well as similar efforts across the country — will be undermined by the “culture of punishment.”

“It’s really ingrained,” Smith said. “We lock them up to ‘teach them a lesson,’ but it’s not good lessons.

“I see a lot of repeat kids,” she added. “They’re not very successful when they come back out. … The division’s goal is to help families, but somehow that shifts when a kid is confined.”

‘WASTE OF TIME’

Former incarcerated youth Thomas, now 18, was held nearly five months at the Dermott Juvenile Correctional Facility until his release last August.

“I was getting treatment once, maybe twice a month, and this was going on for a while,” he said.

He began to get weekly treatment sessions, he said, only after the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette wrote a May 2018 article about conditions at the youth prison.

Thomas was sent to Dermott for nonviolent offenses related to drug addiction, after violating the rules of drug court, juvenile probation and other court-ordered programs intended to help kids with substance abuse disorder.

Before arriving at Dermott last April, he spent more than 100 days without drug counseling in county detention.

Most county youth jails — where many teens languish for weeks or months while awaiting placement in a state facility — lack treatment programs to help kids improve decision-making, anger management or overall mental health, or deal with drug problems.

Bobbie Gross, Thomas’ mother, said they received family therapy over the phone less than monthly until the newspaper article’s publication. Then therapy jumped to twice a month.

The Dermott facility staff never notified her in advance about the therapy sessions, she said.

“They didn’t accommodate you, and it was never a set day,” Gross said. “You just get a call whenever — 11 a.m. on a Wednesday, 6:30 on a Thursday. If I couldn’t answer, I wouldn’t have a family session.”

Youth Services Division officials said the agency aims to improve family engagement to include working around parents’ schedules, encouraging youths to stay in touch with relatives and creating special family events.

To Kristyn, a 17-year-old from northeast Arkansas, the substance abuse treatment offered at the Mansfield Juvenile Treatment Center was a “waste of time.”

“They put other kids in that drug treatment program there who didn’t need it and took it as a joke,” she said. “The people who needed it can’t take it seriously or they were embarrassed about participating.”

Before she was transferred to the state-run center in Mansfield, Kristyn also went months without receiving any substance abuse counseling at county juvenile detention centers.

In February 2017, a Democrat-Gazette reporter observed 17-year-old Jordan in a state lockup ask the facility director why his release had been delayed several weeks.

Jordan, who was at Colt Juvenile Treatment Center in St. Francis County, had completed all treatment plan requirements, except a single drug and alcohol counseling session. Because of staffing shortages and high turnover, he had no way to see a counselor.

Jordan didn’t struggle with substance abuse.

“I’ve been here for four-and-a-half months,” he told the newspaper afterward. “I’m ready to go back. I want to get started at college.”

Vickie Richardson, a Jacksonville mother, said her 13-year-old son was in at least two or three county facilities before getting treatment.

He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings, after he finally arrived at a state juvenile treatment center.

Incarcerated young people have high rates of unmet health needs.

According to a February 2017 article in Pediatrics, the journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, 46 percent of newly detained youths have acute medical needs that require immediate attention; 70 percent have at least one psychiatric disorder.

Arkansas doesn’t track how many youths are committed with unmet psychiatric needs.

“He spent ages 13 to 18 in the system,” Richardson said of her son. “He got bounced around. … That is what they do. They bounce them around, and their time starts all over.”

‘BARE-BONES EDUCATION’

Kids’ educations fall short while incarcerated, said Tom Masseau, Disability Rights’ executive director.

For instance, the staff at the Dermott facility told Disability Rights inspectors that they were ordered to limit how many youths they classified as students with special education needs.

Federal law requires schools to identify all students who have disabilities and to develop learning plans that take their needs into account. Such accommodations often require hiring extra teachers and instructional assistants.

“Failing to identify disabilities in these kids has serious consequences,” Masseau told the newspaper. “They don’t successfully transition back home. It’s harder for them to complete high school and go on to any postsecondary opportunities.”

In 2017, the Youth Services Division hired a new education director, who ensures that the lockup workers meet all special education requirements, officials said.

Past Disability Rights inspections showed that kids often watched movies or played video games instead of going to class, and that teachers used decade-old textbooks. During so-called elective period, children lounged or went outside, weather permitting.

The Youth Services Division changed the education program at all juvenile treatment centers last fall.

Most teachers were replaced with “coaches,” who were required to have only high school diplomas. Kids now sit in front of computer screens for about eight hours a day, receiving instruction through Arkansas Virtual, a state-accredited online curriculum.

Officials say the division’s switch to Arkansas Virtual makes it easier for incarcerated children to earn school credits and transfer those credits upon return to their home schools.

Special education teachers remain at each facility.

Several teenagers who’ve been adjudicated in the past two years told the Democrat-Gazette that transferring from facility to facility made it confusing for school district administrators back home to keep up with the youths’ earned credits.

Nancy Crumbaugh, an Arkansas State University-Newport instructor of adult education, said the lockups’ education program was more robust before the state took control of the facilities in January 2017.

“We were all good teachers,” said Crumbaugh, who taught at the Harrisburg Juvenile Treatment Center. “But for the nearly 14 years I was there, I was never assessed by an education person. The state never assessed us. They never gave us an evaluation.

“And then with Arkansas Virtual, well — I don’t like being just a baby sitter,” she said. “I felt like that’s what I was doing. … It’s a shame because teachers could be really good role models for these kids, especially when they’re having a bad day.”

Dr. Betsy Speck-Kern, a Little Rock neuropsychologist, thinks educational programs in juvenile detention focus too much on behavior.

“There’s less of an emphasis on academics, so the aspirational-level is decreased,” Speck-Kern said. “You’re not going to have the opportunity for field trips. You’re not going to have specialized classes. It’s a bare-bones education in the jail.

“Kids absorb a lot about what the expectations are from those around them.”

‘RELATED TO SURVIVAL’

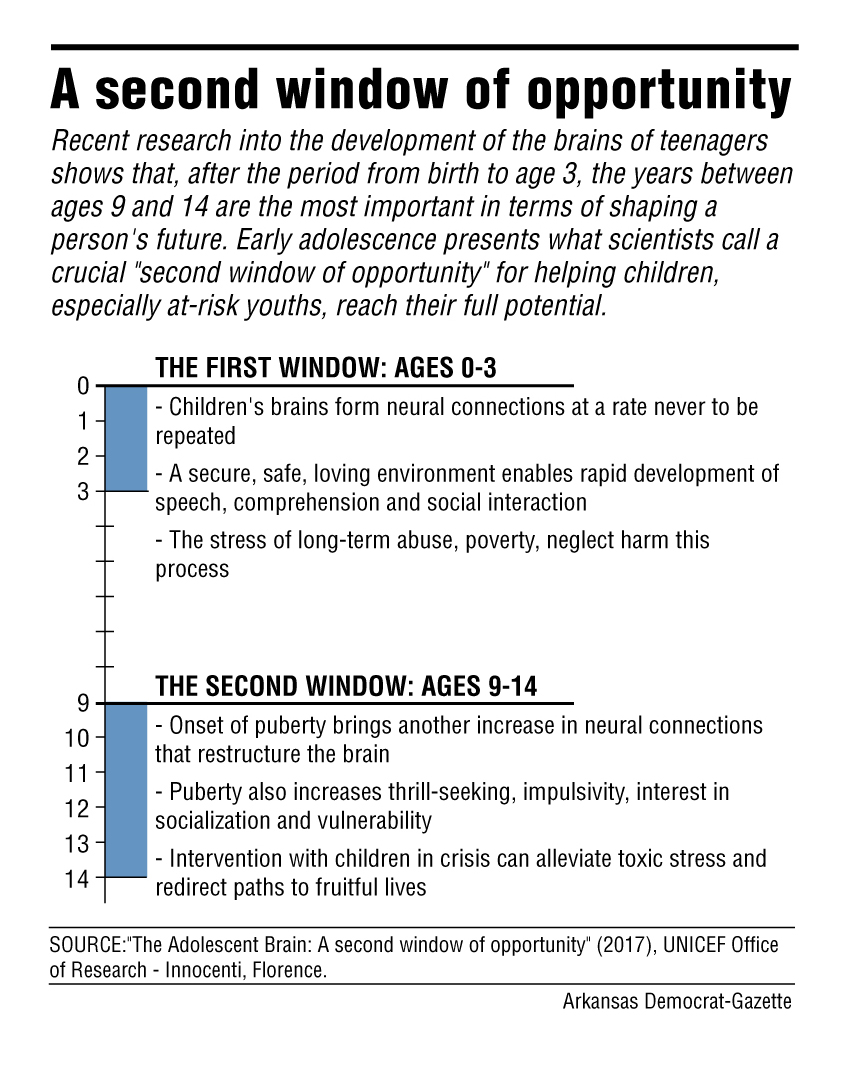

Treatment programs in Arkansas’ youth prisons fail to recognize how adolescents’ brains work, causing further harm to incarcerated children, experts say.

Understanding teenage brains should drive how jailed kids are treated, said Rebecca Shlafer, assistant professor in pediatrics at the University of Minnesota.

Their brains differ from adults’ and constantly produce synapses, the connecting points between billions of brain cells — making adolescence a “second opportunity for development and growth,” after the important first three years of life, Shlafer said.

“Recognizing that adolescence is a second window of opportunity for rehabilitation is critical,” she said. “That really means that adults and systems intervening can make a difference.”

Shlafer has been researching issues related to children and families affected by incarceration for the past 15 years.

The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that handles self-control and decision-making, doesn’t mature until a person’s mid-20s or later, national research shows.

Signals in adolescent brains don’t move fast enough to regulate emotion, and teens are more likely to engage in risky or impulsive behavior.

Little Rock psychologist Dr. George De Roeck said sentencing kids for long periods often adds to their trauma and makes it more difficult for them to adjust when they get out.

The ongoing lack of support “primes” youths, De Roeck said, explaining “their aberrant behavior is all related to survival.”

Prolonged exposure to violence and maltreatment creates significant biological effects, forcing a young person’s brain into “fight, flight or freeze” mode, according to a 2015 article in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America.

Other biological effects include poor decision-making and cognitive function, and an increase in negative thoughts, the article found.

“Incarceration needs to have a strong rehabilitative component,” De Roeck said. “Otherwise, we, as a society, are sowing the seeds for further acting-out behavior and negative peer influence from others in the juvenile-justice system.”

The Youth Services Division plans to hire a private contractor by May that uses “trauma-responsive interventions” at the juvenile lockups, said Marci Manley, a spokesman for the Department of Human Services, which oversees the division.

Under “trauma-responsive” or “trauma-informed” methods, facility workers are trained to understand the physical, social and emotional impact trauma has on children. Facility programs should emphasize youths’ rehabilitation and build resiliency, rather than focus on punishment.

Youths would practice coping skills to recover from past traumatic events, for example. Studies show that these events, often called “adverse childhood experiences,” significantly increase a youth’s chance of entering or re-entering the juvenile justice system.

“We want youth to heal while they are with [the division] and to leave with better coping skills and resources than when they arrived,” Manley said. “Approaching behavior intervention from a trauma-informed perspective also yields better and longer-lasting results. … It improves safety not only in facilities, but also in the community.”

NOT REALLY FREE

Colton returned home to Springdale nearly a month after his third escape attempt. He said he ran that last time for the same reasons — not getting the help he needed.

When he decided to bolt, his arms still had visible scars from the lockup’s razor-wire fence that he had tried to scale in an escape months before.

This time, after guards took him back to the youth prison, the Youth Services Division staff finally listened to him, he said.

Colton recounted the time guards placed him in a chokehold and pepper-sprayed him in the eyes, even though he remained calm and wasn’t resisting; the time another youth punched him in the face, knocking out a tooth, and the staff didn’t take him to a dentist; the time seven kids entered his room and beat him up as staff members watched, cursing at him and taking photos.

Carmen Mosley-Sims, an assistant division director, told him that if he behaved for 30 days he’d be released, he said.

It marked the first time he had a release date. Hope glimmered. He went home in December 2017.

A half-year after his return home, Colton told the newspaper that he resented how long it took to get out.

He still doesn’t fully comprehend how breaking curfew and joy riding landed him there.

He says he’s gotten his life in order — he worked for a while as an industrial tooling supplier and then moved into a corporate office recruiting truck drivers. He wants to run his own business one day. He says he “lost a lot of time” with his sick father, who died four months after his release.

“The only lessons I learned when I was there were self-lessons,” he said. “I’m finally out. And I have this feeling like I’m free, but then I’m really not.”

HOW WE DID IT

Arkansas shields public access to juvenile court records and other information about what goes on in its youth prisons. |