HOT SPRINGS VILLAGE — Doug Maltby opened his scrapbook to a document yellowed with time and ran his fingers over the list of infantrymen and ammunition that filled his U.S. Army glider on June 7, 1944, when he nosed it into a field on the front lines in Normandy.

The letters pounded onto each line by a typewriter so many years ago appear almost fragile today.

But like Maltby’s aged hand, looks can be deceiving.

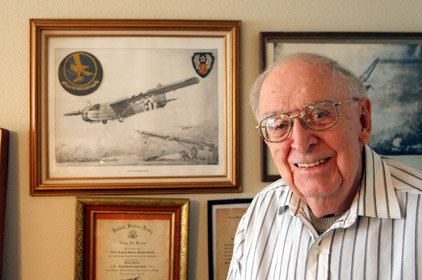

Maltby’s 92nd birthday is just weeks away and his handshake is as firm as his mind.

The words are a bit faded on that old flight manifest he studied. But they remain strong and alive with history, holding details that otherwise would be lost about Operation Hackensack - the resupply mission into Normandy the day after D-Day.

The document shows Maltby’s signature as pilot of the engineless glider, a list of one quarter-ton trailer, several gallons of water, 10 cratesof 60mm mortars, 11 boxes of anti-tank mines, one mine detector and the names of six young infantrymen he was to safely get to the ground.

It was a mission very much like those being flown in Afghanistan today. But instead of gliders flying troops and supplies to precise locations on the front lines, computer guided airdrops with self steering parachutes are being used to resupply troops.

Men like Maltby helped build the foundation of tactical airlift in World War II through trial and error amid gunfire and chaos.

“This is where it came from,” Maltby said. “This is where it started.”

And Operation Hackensack - the first real test of gliders - was Maltby’s first combat mission.

“We’d done nothing but practiced in England for months,” he said. “We were young and ready to go.”

The bloody and brave story of D-Day, June 6, 1944, has been captured by Hollywood, etched into tombstones and told by survivors. It is called the turning point of the war, when the allies broke through the German line in northern France.

But D-Day was much more than a day - it kicked off an 11-month push toward the Nazi homeland. And it would not have been possible without gliders flown to the front line to resupply troops.

The airborne dropped into Normandy with a day’s supply of ammunition, fuel and food. Airborne medics carried little more than bandages and morphine.

The gliders swooped in from above, towed to the front line on 300 feet of nylon rope behind a C-47 cargo plane. The glider pilots disconnected from their tow planes less than 5,000 feet above land and guided their engineless crafts down into fields amid gunfire to resupply troops on the front line.

“This was the start of troop carriers,” Maltby said. “This was the foundation of today’s airlift.”

There were no runways, no prepared landing zones. Landings were made right in the middle of the fight.

On June 7, 1944, Maltby cut loose and started his turns, maneuvering toward the hedgerow-lined field below.

“We had to keep it flying fast enough to have lift and the way you do that is point the nose down,” he said. “If you don’t, you tip, go down and it’s over.”

As he pointed the glider downward, he realized the 8- to 10-foot-tall hedgerows he had been told to expect were more like 30-foot trees. The gliders began to take fire almost immediately, with the Germans shooting at the aircraft all the way down.

Maltby had affixed a piece of steel to his seat before they took off that day. Still, he said, it wasn’t really much protection in a glider made with a wood and steel frame covered in canvas.

Maltby pulled his knees up toward his chest and tucked in his elbows, holding imaginary flight controls in his hands as he told the story from a chair in his home office. It’s all he could do that day, too, tuck up, become small and fly all the way to the ground.

“They told us we could just go through the hedgerows,but when we cut loose and I saw the 30-foot trees, I had to get over those to land.”

But they weren’t coming in fast enough. He decided to drop it in and land before the trees.

“I tipped a wing and dropped in from about 50 feet,” he said. “We hit so hard, the wheels collapsed.”

Everyone walked away unscathed.

More than 1,000 gliders landed in Normandy that day as part of Operation Hackensack. Not all of their pilots lived. Pilots who survived walked miles back to the channel coast, where they caught a boat ride back to England to prepare for their next glider mission.

“A good landing in a glider is one you walk away from,” he said with a smile. But it was no joke: landings were considered controlled crashes.

For that reason, many troops called the Army’s CG-4A gliders “flying coffins.”

“Some did,” Maltby said without even the hint of a grin. “I didn’t.”

Glider pilots had the highest death rate in the U.S. Army Air Corps - what would eventually become the U.S. Air Force - in World War II. According to the American Glider Pilot Honor Roll, glider pilots averaged a 20 percent casualty rate for each mission. With just a canvas skin and a slow descent, they were easy targets.

Today, their biggest threat is time.

Maltby turned his eyes to a picture on a nearby wall. In it, he stands with a group of his fellow World War II glider pilots at a recent reunion at the Air Force Museum in Ohio.

His eyes grew hazy as his mind went back to the war and the men he knew.

“I just got a telephone call,” he said, still looking toward the picture. “We lost another one yesterday.”

That sort of phone call comes more frequently these days. But the pilots’ legacy lives on in more than scrapbooks and memories.

World War II brought the biggest jump in airpower technology in history, said Ellery Wallwork, historian for the U.S. Air Force Air Mobility Command. Diverse and specialized aircraft were developed and the various uses for each aircraft were tested and expanded from then on.

“Technology quickly moves forward in a war,” Wallwork said.

The glider program was started as a way to accurately get troops and supplies to the front lines. In World War II, the science of airdrops was still new and still rather inaccurate. Having a pilot fly a glider filled with troops and supplies was much more dangerous, but also much more reliable.

The glider program was discontinued after the war as better airdrop tactics and cargo planes were developed.

Today’s technology, however, has gone back to the concept that first led to gliders. Today the JPAD system - joint precision airdrop - uses GPS technology and motorized self-steering parachutes that guide pallets to the ground with more accuracy than ever before. The program is being used extensively in Afghanistan, where airlift and airdrop are being used more for sustainment operations than ever before.

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” Wallwork said. “It’s a different aircraft, but it’s a similar mission with similar goals. ... And it’s still the same living conditions, in many cases.”

Maltby spoke fondly of the days living in a tent with other crews during the Holland campaign. They ran electricity to the nearby outhouse so they could listen to the radio while using the facilities. C-130 crews live in similar tents in Afghanistan today just as they did in the early days of the Iraq war, rigging lights and air conditioning and even makeshift walls and shelves out of scrap wood.

The tie between the generations of airlifters is strong. Maltby’s old unit, the 103rd Troop Carrier Squadron, is now the 103rd Airlift Squadron at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, Calif. It flies C-17s, jet-powered cargo planes used throughout Iraq and Afghanistan for strategic airlift such as quick evacuation of wounded from the war zone to Germany or even straight back to the states.

“It’s a section of your life you’ll never forget,” Maltby said. “It ties us together.”

Pictures of gliders and memorabilia decorate the hallways of Little Rock Air Force Base’s 62nd Airlift Squadron, 314th Airlift Wing. The 62nd trains new C-130 crews these days. But back in World War II it flew C-47s and gliders as the 62nd Troop Carrier Squadron.

The World War II crews hold a reunion every year in conjunction with the 62nd’s Christmas party. The older veterans have been holding a bottle of wine to open when there were just a handful of them left.

They cracked the bottle open a few weeks ago at this year’s reunion.

“It’s kind of sad, really,” said Senior Master Sgt. John “Red” Smith, a flight engineer with the 62nd. “They are our history.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 12/28/2009