LITTLE ROCK — A research and tourism frenzy sparked by reports that one of the rarest birds in North America - the ivory-billed woodpecker - had been rediscovered has all but evaporated a half-dozen years after the initial sighting.

With no hard evidence confirming the bird’s existence, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which lent its prestige to the effort and organized systematic searches of the thousands of acres of swampland near the Cacheand White rivers, has concluded it has neither the personnel nor the resources to continue similarly elaborate searches.

“The preliminary conclusion from the search efforts suggest that there aren’t recoverable populations in the places we have systematically searched,” said Ron Rohrbaugh, director of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Research Project at the ornithology lab, which is part of Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

And while the lab’s re-searchers will continue to sift the data collected in those searches - to be published in a book, so far the research shows that if the bird does exist in the Big Woods, it is likely few in number, he said.

The lack of confirmation is why the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stopped funding the searches, said Tom MacKenzie, a spokesman in the agency’s Atlanta office, which oversees the southeast region of the United States, including Arkansas.

“We still believe it could be out there, but unless we know for sure, we have to be wise with our resources,” he said in an interview. “We still hope it’s out there. We haven’t given up hope.”

However, the Fish and Wildlife Service is still preparing to release a recovery plan for the ivory-billed in the event its existence is documented. Also, other agencies have altered practices, such as timber management plans, based on the premise the bird exists.

Since the initial reported discovery in 2004, the Fish and Wildlife Service spent $14 million to document and conserve the woodpecker in the southeastern United States, according to an article in the February issue of Nature magazine.

The money included $8 million for habitat preservation and $2 million for search associated costs.

The money included $1 million split between the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission and the Arkansas Heritage Department for land preservation, said David Goad, the commission’s director of wildlife. The Arkansas Nature Conservancy provided the local matching money, he said.

Many say the increased acreage placed under protection may be the lasting impact of the search.

“That’s going to be a positive benefit that will be there for generations,” MacKenzie said. “It makes people more appreciative for what we’ve got.”

Gene Sparling of Hot Springs agreed. It was his spotting of the bird while kayaking in the Big Woods in 2004 that sparked the renewed interest by researchers.

“The habitat is worth saving over and above the ivory-bill,” Sparling said. “It’s a fantastic, unique, wonderful habitat. We need to take real good care of it.”

The spurt of activity produced little additional hard evidence beyond grainy video footage that searcher David Luneau carried out of the area of east Arkansas known as the Big Woods six years ago. The footage showed a black-and white woodpecker with the apparent size and plumage patterns of an ivory-billed fleeing through the forest. The video has been disputed by some, who say it could bea pileated woodpecker, which bears some resemblance to the ivory-billed woodpecker.

Other scientists, primarily with Cornell, also reported seeing the bird more than a half-dozen times. After a year of secret searching, the researchers announced the bird’s rediscovery in 2005. But since then, they were unable to provide evidence confirming it.

Rohrbaugh can’t precisely say how many ivory-billeds would be enough for a recoverable population, but he said he is certain it would be more than one pair. And if there were more than one pair - say 20 - given the search parameters, they would’ve been spotted.

A 2008 paper written by Rohrbaugh, J. Michael Scott of the University of Idaho and five other scientists, concluded that statistically an ivory-billed should have been found if a recoverable number existed.

“Given the detection probabilities we used, this survey effort yielded roughly a 93 [percent] chance of detecting at least one individual from a population of 20 birds, a 74 [percent] chance from a population of 10, and only a 49 [percent] chance if five individuals were actually present in the study area as a whole,” the authors wrote in the paper, “When is an ‘Extinct’ Species Really Extinct? Gauging the Search Efforts for Hawaiian Forest Birds and the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker.”

“Thus, given this search effort, if more than a very few Ivory-billed Woodpeckers were present in the search area during the surveys, their presence should have been detected.”

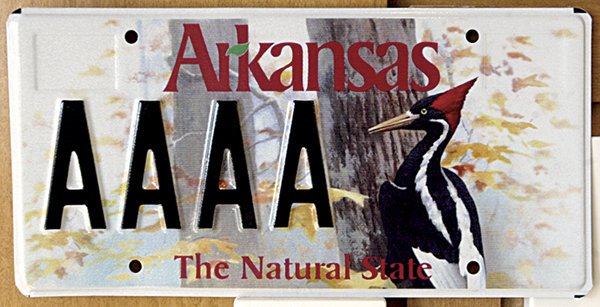

The falloff in activity and interest by researchers has produced a corresponding drop in interest by the broader public. As an example, the special license plate featuring the ivory-billed woodpecker issued by Arkansas illustrates the rise and falloff of interest.

The plates went on sale in December 2005. By November 2006, fans of the bird scooped up 3,035, according to the Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration.

Interest began waning in 2007 when only 635 more plates were sold, department figures showed. Interest has fallen off dramatically in subsequent years. By December 2008, the number of plates in circulation increased by only 68, to 3,747. A year later, circulation rose to 3,795, an increase of 48. By January of this year, the number of plates in circulation had declined to 3,720.

For Brinkley, a Delta town used as a base by the scientists, birders and tourists who flocked to seek evidence of the bird, 2006 was the big money year.

“This is where it was happening,” recalled Ronnie Steinbeck, who has lived in the area 14 years and guides tours for a living. “It didn’t do nothing but help Brinkley and Monroe County. People still come in and ask about the ivory-billed every week.”

Steinbeck said he was running two boat tours a day from his business, Paradise Wings Lodge, which is about seven miles from where the bird was said to be spotted in 2004. “I had people on a waiting list.”

Still, even at its height, the birding business didn’t compare with his main source of income, guiding duck hunters.

Today, Steinbeck still advertises birding tours on his lodge’s Web site, but interest in the tours has fallen off. “I had a group scheduled for May, but they called last week and canceled.”

While well-funded searches may no longer occur, some still search on their own.

Luneau, who teaches at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, still goes out on most Fridays to search for the bird and more evidence.

“I believe that the Ivorybilled Woodpecker still exists, but I also believe that its population must be critically small,” Luneau said in an email.

“But, the population has probably been critically small for the past 65 years or more, yet the bird continues to survive.”

To Luneau and others, that doesn’t mean the ivory-billed woodpecker isn’t out there, nor do they believe the search was entirely fruitless. The effort drew renewed attention to the Big Woods, helping to add acreage to the area as it raised the profile of the second-largest woodpecker and of conservation in general.

Luneau credited Cornell’s involvement, which he said drew serious attention to thebird and attracted money for the search effort. The Nature Conservancy also was a big help in raising money to conserve “thousands of acres of bottomland hardwood habitat.”

“The search effort has had a positive impact on eastern Arkansas that will, in the long term, benefit bird and birders as well as wildlife and hunters,” Luneau said.

The ensuing benef its from the search even won over skeptics such as Jerome Jackson, a professor at Gulf Coast State University in Fort Myers, Fla., who questioned the science behind the confirmation of the ivory-billed’s existence.

“In truth, it took the publicity, and the ‘declaration of confirmation,’ as well as political connections, to get the funding for the search and to capture the imagination of the American and even the foreign public in order to accomplish the searches,” Jackson said.

He concedes the effort behind the search hasn’t been a waste, since “less glamorous” species are going to benefit from the conservation effort.

“The expenditure of funds to acquire bottomland forest habitat for conservation is a definite plus,” Jackson said. “The White and Cache rivers, and other north-south flowing rivers in the southeast, are green corridors essential to migrant songbirds as they wing to and from the American tropics, delivering songs to backyards across eastern North America each spring.”

Front Section, Pages 1 on 04/23/2010