This article was originally pubished on May 19, 2008.

LITTLE ROCK — Second of two parts

When victims of Wayne Watkins' failed land deals turned to government agencies for help, they felt further victimized.

"It was all one big shady deal, and it appeared that the people who were supposed to protect us lowlifes did nothing," said Domenico Cossu of Hardy, who filed one of the earliest complaints against Watkins.

But determining who had a duty to protect buyers isn't easy.

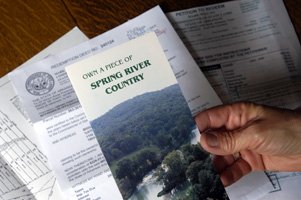

Watkins, who turns 60 in July, spent more than two decadesdeveloping family and camping resorts along the Spring River, selling hundreds of lots mostly to out-of-towners.

For reasons that aren't clear, some buyers gained clear title to their land after paying off their installment land sales contracts. But others lost their money and their land after several banks foreclosed on Watkins when he defaulted on $2.6 million in loans he obtained by using the land as collateral.

Why? Because Watkins did not routinely file the ownerfinanced sales contracts at the courthouses in Sharp and Fulton counties. That would have connected the buyers' names to the land - notifying potential buyers or lenders that they had an interest.

Other buyers have learned that their property, along with hundreds of other parcels, has been turned over to the state for back taxes - taxes they say Watkins' salesmen promised would come out of their monthly payments, but which their written sales contracts said was their responsibility.

The Arkansas attorney general, whose Web site touts the office as the state's chief consumer advocate, has received 22 complaints about Watkins - dating back to 2003 - but neither Dustin McDaniel nor his predecessor Mike Beebe, now governor, has taken any action against the Sharp County developer.

"Now we have nothing, and nothing is being done about it ... while the [Spring River] Beach Club owner is sitting down in Mexico spending beach club money," Nora Ferguson of Osceola wrote the attorney general's office in July 2007. "He needs to be held accountable."

Watkins now lives in Mexico, where he sells real estate. Through a relative, he declined comment.

Deputy Attorney General Jim DePriest, who also served Beebe, said McDaniel ultimately decides how to spend the office's resources.

"We get approximately 6,000 formal consumer complaints a year, so not all of them turn into lawsuits," he said. "We try to get responses and get resolution, but it's a resource thing."

The Real Estate Commission investigated and then dismissed a complaint it received in 2005 that Watkins sold property that didn't have a clear title, a problem that has pulled land outfrom under scores of buyers who planned to use the property for vacations or retirement.

Some of Watkins' victims say state Land Commissioner Mark Wilcox's office, which handles tax-delinquent property, gave them misleading advice - advice that gave them false hope of gaining ownership of the land and cost them more money.

Wilcox declined an interview for this story, but his employees defended the office's practice of urging people to pay back taxes on property that may or may not belong to them.

"It's sending out a message that people shouldn't buy land in Arkansas," said Ronald Falanga of Memphis, who spent $23,000 on land he and his wife will likely never own.

In November, Falanga and his wife, Lynne, learned that Watkins had never recorded their 2003 contract for purchase and had left the country.

Still reeling from that news, the Falangas discovered that Watkins also hadn't paid taxes on the property for several years and that the land would soon go up for public auction.

Desperately seeking to save their investment, the Falangas called the land commissioner's office . An employee advised them that the only way to keep the property off the auction block was to pay $700 in back taxes.

The couple insist that more than one person at the land commissioner's office told them that if they paid the taxes, they would own the land.

The land commissioner's chief deputy, Bentley Hovis, said the office would never tell someone that paying taxes on land would make the land theirs. The Falangas must have misunderstood, he said.

"There's no way the land commissioner could do that," Hovis said. "If you come in, and you're an interested party, we let you pay the taxes."

Hovis acknowledged that getting the taxes paid is the main priority of his office.

Tim Grooms, a Little Rock real-estate attorney, said that based on his years of experience with the commissioner's office, he would be surprised if the office suggested that payingtaxes on property could lead to ownership.

Yet, the Falangas, thinking they'd get to keep the land, delayed paying the mortgage on their Memphis home to cover the Arkansas property's back taxes.

In exchange for the Falangas' $700, the office sent the couple a "redemption deed," which Hovis described as "just a big receipt showing that the taxes have been paid," not a transfer of title.

The Falangas' redemption deed lists "Spring River Beach Club Inc." as the property owner but also shows the Falangas as having an interest in the property.

The property remains in Watkins' name. Land commissioner staff attorney Carol Lincoln said that the only way that will change is if a judge changes it.

The Falangas argue that simply telling people to pay taxes on land is deceptive.

After reporters for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette told Hovis that the Falangas' sales contract had not been recorded, he offered to refund their $700, but later rescinded the offer. In April, after talking to reporters again, he returned the Falangas' money.

"We want [the contract] to be recorded. If it wasn't a recorded contract, we probably shouldn't have [accepted the contract as proof of an interest]," Hovis said.

But because the Falangas paid the taxes, they have a recorded interest in the property and recently received a 2007 tax bill for the property from Sharp County.

Hovis conceded that the land office made exceptions to its normal protocol for the Falangas and others who thought they were buying land from Watkins.

The commissioner's staff made the exception because they knew about Watkins' troublesome history.

"Our experiences with Wayne Watkins are not new," Hovis said. "He's had land sold at public auction for years."

In fact, the office removed 97 of Watkins' parcels from a scheduled public auction last year because it learned of a foreclosuresuit.

"If we did sell them," Hovis said, "... that adds another layer that complicates things."

In March, the Bank of Salem filed a foreclosure lawsuit in Sharp County. Among others, it named the Falangas and the land commissioner as defendants.

Hovis said his office didn't know the Falangas' land was the subject of a foreclosure when it took their money.

"Had we known about the foreclosure, we wouldn't have let you pay the taxes. Period," he said.

The land commissioner issued the Falangas' redemptiondeeds on March 24 and filed them in the Sharp County clerk's office - the same office where the Salem bank had filed its foreclosure suit 12 days earlier. Hovis said his office didn't become aware of the foreclosure until March 31.

That lawsuit includes six of the more than 600 pieces of land the commissioner can put up for sale because back taxes are owed.

Since the office routinely refrains from selling property at auction when it has been informed the land is involved in foreclosure proceedings, Hovis said the commissioner likelywon't put those parcels up for auction.

The commissioner hasn't decided whether to proceed with a scheduled auction of 57 other Watkins parcels this summer.

Watkins' land has been the subject of at least three other foreclosure lawsuits, but the land commissioner isn't surewhether any of the auction-ready properties are included in those suits.

Although the office spends about $1 million a year on title searches, it has historically researched only those parcels assessed at $4,000 or more. Last year, the officelowered the limit to $2,000. The assessed value is 20 percent of the market value. Hovis estimates the office spends $100 to $150 per parcel on title searches.

People who buy property at auction are encouraged to conduct title searches, but most buyers don't, said Lincoln, the commissioner's staff attorney.

Her office won't alert callers or buyers at auctions that Watkins' land may be the subject of fraud or foreclosure, she said, because that would be giving legal advice and open the office to liability.

"I don't want to sound like we don't care, because we do," Lincoln said, "but in terms of whether or not it's a burden on us to go out there and determine which property has been foreclosed on and what hasn't, that would be something we generally don't do."

Although the attorney general's office has not acted on the 22 complaints against Watkins,DePriest said he won't rule out the possibility that the office may engage in a more aggressive look at Watkins.

"I'm sensitive to people saying, 'You've got to do something,'" he said. "We may still jump in the game. We may decide that this has just become so important to so many people that we need to pull resources from another place."

DePriest said that severalcomplainants indicated they've hired private attorneys, something the office considers when deciding whether to proceed with an investigation.

Not all of the people who complained, however, have contacted lawyers, according to the complaint files.

"We have been paying as we promised and recently learned to our horror, that we were scammed," Blytheville resident Shannon Hovis (no relation to Bentley Hovis) wrote in her May 2007 complaint. "We are devastated and do not know what to do!"

The attorney general has the power to prosecute civil cases on behalf of the public, according to Arkansas Code Annotated 4-88-105.

According to the office's Web site, the attorney general could file a lawsuit "when there is a compelling public interest present or when many complaints exist."

In those cases, the office attempts to obtain refunds for consumers and civil penalties up to $10,000 per violation.

But the office has done little more than ask Watkins for responses to complaints and advise victims to hire an attorney or go to small claims court. Watkins rarely responded.

"These are good honest people that have paid ... to have a weekend place of their own for their kids and grandkids to enjoy," Laveral Rogers of Beech Grove wrote in May 2007. "Wayne Watkins and some area banks are taking that away fromthem."

Brenda and Jim Roweton of Hernando, Fla., also filed a complaint with the attorney general earlier this year and have followed up with the office's requests for more detailed information.

So far, they aren't encouraged.

In a March 11 letter, Karen Keyes Diner, an investigator in the office's consumer protection division, replied to a letter from the couple, asking them: "Who is David Huffmaster? What 'charges' didyou file?"

Huffmaster is a detective with the Sharp County sheriff's office whose work prompted a judge to issue a warrant for Watkins' arrest more than a year ago.

In March 2005, Domenico Cossu of Hardy tried to sell land he bought from Watkins. During a title search, the potential buyer discovered Watkins sold Cossu land without a clear title.

"All sorts of stuff came up," Cossu said, adding that Watkins had used the Fulton County property as collateral at two banks.

According to Cossu, Watkins' salesman, Howard Baswell, discouraged him from a title search when he bought the property in 2001, saying, "You're dealing with us."

In the summer of 2005, Cossu filed complaints with the attorney general and the Real Estate Commission. Watkins finally provided Cossu clear title in late July - after the developer received letters from both agencies.

"Sorry for the problem, but this loan was sold to 4 different banks," Watkins wrote to the commission.

A commission investigator noted in Cossu's file that Watkins "claimed no prior knowledge" of the title problems.

Watkins, a licensed real estate broker since 1974, let his license lapse in December 2005 and closed his real estate company, commission records show. The investigation also noted that Watkins said he did not advertise Cossu's property and had stopped advertising his Spring River Beach Club properties in 1990.

Yet Cossu and others who talked to the Democrat-Gazette have said they found the property they bought in advertisements years after Watkins allegedly stopped advertising.

Bill Williamson, the commission's executive director, said that Cossu's complaint about Watkins didn't raise concerns that there might be a larger problem.

Still, there is a slim chance Williamson's office could help those who lost money recover some or all of it, he said.

The Real Estate Commission has a "recovery" fund it can use to compensate people, provided they file a successful complaint before a three-year deadline expires. The three years start on the date of purchase.

"We really can't determine whether the statute of limitations would apply until we get something in writing, a complaint," Williamson said, adding that if Watkins concealed informationor defrauded buyers, the deadline could be waived.

The commission may not have authority to intervene if a sale took place after Watkins' license expired. But if it can act, and it determines that Watkins violated the Real Estate License Law and that a buyer was "damaged" as a result, Williamson said the commission could order Watkins to compensate buyers who complained.

If 30 days passed without payment, the commission can pay the wronged buyers from its recovery fund. The fund has a capof $75,000 per licensee, regardless of how many people prove they were cheated by Watkins.

Some people aren't optimistic that Watkins will be held accountable.

"I don't have a lot of confidence that anybody is going to do anything," said Art Temple of Alabama, whose land also has been turned over to the state for auction.

Sen. Paul Miller of Melbourne, whose district includes Sharp and Fulton counties, has been involved in real estate for more than 30 years. He said he had not heard about the problems with Watkins' land dealsuntil contacted by a reporter.

Miller, a Democrat, said he plans to investigate possible changes to state law, such as requiring sales contracts like those signed by Watkins' buyers to be filed with county clerks.

He explained that he doesn't want people thinking buying land in Arkansas is a risky investment.

"I'm going to try to fix it - in the future," Miller said. "There's nothing I can do to help those people who are already in a bind." E-mail the reporters:

or

Front Section, Pages 1, 6, 7 on 05/19/2008