LITTLE ROCK — “It’s hard not to romanticize baseball.” The line comes up a couple of times in Bennett Miller’s remarkable Moneyball, a movie about, as much as anything, seeing past the superficial to the essential - about the deceiving nature of appearances. As such it reverses the usual polarity of Hollywood movies, which tend to sentimentalize and valorize isolated moments of apparent grace.

Hollywood habitually tells us stories about those who have overcome long odds, of underdogs who believe so strongly in their own talent or will that they succeed despite impossible circumstances. Movies are made about statistical abnormalities - about the lucky few who somehow escape the seine net of probabilities.

Moneyball is a movie about process, innovation and the accretion of significant detail. It is about turning what seems dull and base into gold. It is about the kind of alchemy the priests damn as magick. It is about baseball as it really is, not how we imagine it to be.

So you don’t care for baseball, and you think this movie is not for you? Well, maybe not, though if you don’t understand why Brad Pitt is a movie star you will after you see him here. Two-thirds through the screening, I lean over to ask Karen (who prefers her baseball games short and high-scoring) if she’s enjoying herself. She is. She really is.

So my thesis proved correct: Moneyball is not just a movie that will appeal to baseball geeks like me(for the record, I was a hardcore Bill James evangelist in 1981, and I loved the 2003 book - Michael Lewis’ Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game - that inspired the film) - it’s also accessible to folks with only a passing interest in the game. Maybe it will even cause some nonfans to become interested in baseball, although that hardly seems its purpose.

Moneyball isn’t really a baseball movie, or even a sports movie - it feels more like a smart procedural from the ’70s. Like All the President’s Men, some of its most arresting scenes involve a guy talking on the phone. It’s a movie that credits the audience with having an attention span and a clue, that doesn’t reduce a complicated system with thousands of moving parts down to a bumper sticker (or a twoout, bases loaded at-bat).

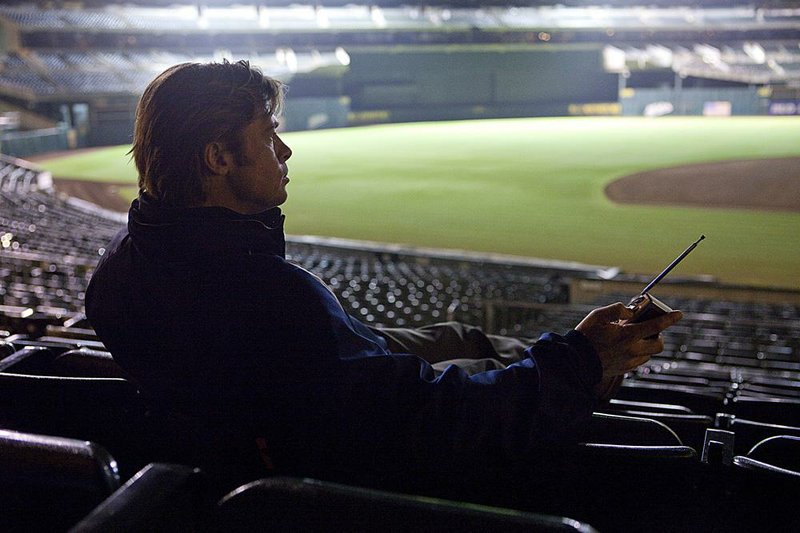

Still, Moneyball is built to entertain, to solicit your empathy for its protagonist - the shaggy Oakland A’s general manager, Billy Beane (Pitt at his most charming and well observed - his antic, glib Beane eats junk and burns it off with obsessive workouts, like a lot of ex-jocks I know). And for his pneumatic, datamining sidekick Peter Brand - underplayed by a restrained, excellent Jonah Hill who has much more on his plate than providing comic relief.

(Brand is based on Paul DePodesta, Beane’s Harvardeducated assistant, who later became the general manager of the Dodgers. DePodesta reportedly objected to the way his character was portrayed, hence the mild fictionalization.)

After the 2001 season, Beane was faced with the unenviable task of rebuilding his team after richer clubs lured away the A’s triumvirate of stars. Beane didn’t have the resources of the Yankees and the Red Sox, he couldn’t simply buy the “best” players available, yet he and Brand used new metrics and computer-crunched algorithms to identify undervalued players who could make real contributions.

A priceless early scene in which Beane meets with the saltiest members of the A’s brain trust (most played by actual baseball scouts) illustrates the chasm between the theology of the baseball establishment and the real world.One of the scouts contends an “ugly girlfriend means no confidence.” Another evokes the “good face” rule - the quasi-Darwinian idea that handsome players are generally superior.

After listening to the scouts go on about how sweet a prospect’s swing is and how the crack of his bat is thunderously different, Beane asks what ought to be an obvious question:

“If he’s such a good hitter, then why doesn’t he hit?”

The truth is there’s only so much any subjective observer can predict about how an athlete will perform as a major league baseball player - most great athletes fail at baseball. (Beane knew this because he was himself a “can’t miss” first-round draft pick, a so-called “five-tool” prospect - he could run, throw, field, hit and hit for power - who never panned out as a player.

And the flip side of this is that players who don’t pass the “eye test” are often precluded from proving themselves as players. As Brand points out, other organizations’ faith based adherence to conventional baseball wisdom made it possible to economically assemble a team of castoffs - “an island of misfit toys” - that could compete with the superstar-studded lineups of large market teams.

Because Hollywood is as conservative and superstitious as baseball, Moneyball was a famously difficult project to bring to the screen, and it likely was made only because of Pitt’s clout. Bennett Miller, whose last film was Capote in 2005, was the third director attached, and it’s probably fair to say he wouldn’t have lasted had he not shared Pitt’s vision for the film.

In any case, it’s a movie filled with delightful grace notes, from Philip Seymour Hoffman’s dyspeptic portrayal of skeptical A’s manager Art Howe and a couple of tender, character-elucidative scenes between Pitt and his preteen daughter (Kerris Dorsey) to a bittersweet ending that will likely surprise any nonbaseball fans who wander in.

Moneyball has the courage of its convictions. That’s not to say it doesn’t make compromises for the sake of the story (it does here and there, it’s not a documentary) but it’s remarkably faithful to the fairly complex actualities of its story.

It resists the temptation to romanticize baseball, for it trusts its audience can handle the truth.

MovieStyle, Pages 33 on 09/23/2011