LITTLE ROCK — Camp counselors live to terrify bug-eyed campers with fireside fiction about the “Hook Man” and that foul fiend with The Golden Arm. But the stories that sink in like fangs, injecting young minds with alarm that tingles decades later - those tales are told in daylight by other little campers, tales about Things That Cling.

Things that cling to the undersides of tarps. Things that cling to the corners of cabins.

To the backs of logs. To that pile of leaves.

We’re talking about - duh duh DUHNnnn - the harvestmen.

And the campers squeal, “Aaeeee!”

Some campers call them daddy longlegs, some call them granddaddy longlegs. Either name: “Aaeeee!”

Supposedly these dads or grandpas lurk about human habitation in a state of frustrated appetite: Supposedly, they yearn to bite us, but their fangs are just too small.

Supposedly, longlegs possess the World’s Most Potent Venom, able to drop a man in seconds flat. But - whew - miserable little mouth parts with shorty-short fangs just cannot get a grip around meaty human ankles.

(To which a scientifical child might reply that chiggers are even smaller than daddy longlegs and that doesn’t appear to stop them from chowing down on ankles.)

But it’s campfire malarkey.

Biologists know the arachnids commonly called daddy or granddaddy longlegs are not the world’s most poisonous spiders. Longlegs are not even spiders - although if you go around calling any spider that has threadlike legs a “daddy longlegs spider,” well, that one would be a spider.

Because common folk do tend to apply common names willy-nilly - to crane flies, to skinny spiders - let’s simplify:The daddy or granddaddy longlegs that are most likely to star in our fireside chats are harvestmen, and harvestmen have no venom.

In the kingdom of animals, phylum of arthropods, they belong to the same class as spiders, ticks, mites and scorpions - Arachnida. But harvestmen are of the order Opiliones, while spiders are Araneae.

Not the same critter.

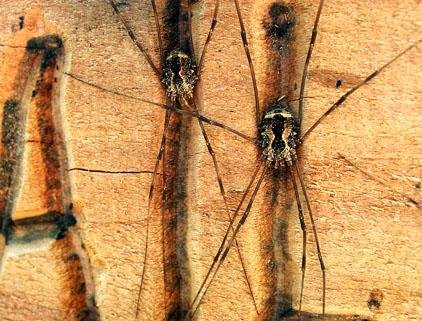

Spiders tend to be solitary hunters, but harvestmen can be flamboyantly sociable, gathering in hairy masses with 25, 50 ... a lot - huddled close, eight legs (or so) apiece and all those freaky legs crisscrossed.

Freaky but harmless, they are harmed by freaked-out humans who don’t like them or the way they smell. And do they ever smell.

The great folktale collector Vance Randolph reported in his 1947 anthology Ozark Magic and Folklore that “an old fellow” in Polk County had once upon a time assured him: “If you mash a daddy longlegs ... it smells just exactly like bedbugs.”

SO MISUNDERSTOOD

As campfire season comes a-creeping, here’s some ammunition with which to arm scientifical kids, so they won’t grow up afraid of the harmless harvestman.

The information comes from Jeffrey Barnes, curator of insect taxonomy and systematics in the University of Arkansas’ department of entomology (who just happened to have delivered a lecture about harvestmen to his taxonomy students the day we spoke); and from the Encyclopedia of Arkansas article “Harvestmen” and its coauthor, Ray Fisher, a doctoral candidate in the UA department of entomology who has a keen interest in the mites that infest harvestmen; and from Henderson State University’s Nature Trivia home page (by Renn Tumlison and Kristen Benjamin) and from assorted books and websites devoted to fun facts and natural science.

How do I know it’s a harvestman and not one of the actual spiders people call “daddy longlegs spiders”?

It might be a spider if ...

It has a web.

It has a waist.

It leaves little bundles of its victims lying about.

If those three hold, chances are it’s also called the “cellar spider.” Cellar spiders also do not have the World’s Most Potent Venom. As spiders go, they aren’t very potent. They shake their webs violently when disturbed, to scare you away; and that’s your easiest clue: Opiliones have no silk and spin no webs.

The second clue is shape. Spiders have an hourglass figure, with a waist where the cephalothorax attaches to the abdomen. Harvestmen’s bodies are globular, like flattened balls or middle-aged former football players.

Photos of harvestmen and also the cellar spider (Pholcus phalangioides) are available at bugguide.net.

Harvestmen don’t eat people, but what do they eat?

The order Opiliones “comprises around 60 families, 1,600 genera, and over 6,500 species,” Fisher says. And those numbers are merely approximate, because harvestmen are not well studied.

Why not? Because they pose no economic or medical threat and there’s no grant money in it, Barnes says, adding that most of the scientists who have studied them did so long ago and now are dead.

The harvestmen we know are drab and hard to tell apart; but around the world, Opiliones come in spectacular colors, some with fluorescent markings. Different species are known to have different diets.

Most are predators that also clean up dead animal and plant matter. Shake out some crumbs to trap ants, and harvestmen will eat the ants and the crumbs, too. They also might hunt insects bigger than they are.

“Sometimes I collect insects at night ... reflecting black light off a white sheet,” Barnes says. “Daddy longlegs seem to realize that there are insects, potential prey, accumulating in large numbers in one area, and they will crawl up onto that sheet and pick off the moths.”

He also finds harvestmen in his cat’s food dish. “This would be wet food, Fancy Feast. It doesn’t seem to matter what variety it is, almost always there’s a daddy longlegs in that bowl.”

Unlike spiders, harvestmen take bites to digest inside their bodies. So they don’t wrap up their prey in silk and turn them into smoothies - as spiders would.

What eats them?

This writer has seen Opiliones being stalked by wrens, toads, cats, lizards. All kinds of predators threaten them, Barnes and Fisher say, including other harvestmen, which sometimes cannibalize tender hatchlings (or adults that just molted but haven’t hardened yet).

They are also beset by another arachnid - mites.

“The mites commonly found on harvestmen are awesome creatures,” Fisher says. “They are all parasites that, like ticks, engorge on host blood” (harvestmen “blood” is haemolymph).

Mites reduce their host’s life span and also how many eggs it can lay. They harm the harvestmen.

“The mites are in a massively diverse group called Parasitengona, that includes the velvet mites, chiggers, water mites and relatives,” Fisher says. “All of these creatures have weird life cycles where they ‘pupate’ - similar to a caterpillar turning into a moth - several times.”

It goes like this: egg, parasitic larva, “pupa,” predatory nymph, “pupa,” predatory adult.

Several kinds of mite attack harvestmen, but the ones Arkansans are most likely to spot are orange-red and of the genus Leptus, Fisher says. “Even though the larvae look like red sacks on harvestmen, the adults can be beautifully colored and even polka-dotted.”

He says that if you (for science and not for sport) were to pull a mite-infested leg off a harvestman and put it in an air-tight jar, the leg would jerk for 20 minutes or so. But “soon, the larval mites will fall off, crawl around and then become inactive. This is the‘pupal’ stage I mentioned.

“Then, in about three weeks, you will have nymphal polka-dotted Leptus.”

Can harvestmen’s legs really tell you where your cows went?

No.

Do the legs grow back?

No. “This of course, makes the common practice of pulling legs off of these creatures even more cruel,” Fisher says.

The legs are sensitive and necessary. “In general, the second pair of legs are long and thin - we call this ‘antenniform’ - and thus specialized sensory organs - as they don’t have usable eyes like us or antennae like an insect.”

Harvestmen’s eyes are dots set on each side of a teeny turret atop the body. It’s thought they see changes in light and movement, but not much else.

In the common group Phalangioidea, Fisher says, the last segment of the long legs is prehensile and can wrap around a small branch or food item two or three times. And harvestmen in the tropics have extra claws and structures on the last two pairs of legs used to help them molt.

Species that don’t live in North America are noted for gigantic spines on their hind legs used to pinch predators. “Some of these are large enough that this pinch can draw blood,” Fisher says, “making them one of the few examples when a harvestman can harm a human.

“Of course they aren’t here, and a pinch, even with a little blood, is still pretty wimpy.”

Why do harvestmen gather in groups?

Barnes says such “aggregation” isn’t a social behavior in the sense that ants or bees are social, with individuals assigned set tasks in a colony. Harvestmen are thought to gather for the same reason that fish form schools: defense from predators.

In a group, they overlap legs. The HSU site explains, “When disturbed, a single harvestman typically pushes its body up and down in a slow, vibrating motion. The large groups will perform the same behavior if disturbed, so the pulsating mass of harvestmen may be an even greater deterrent to potential predators.”

When spooked, harvestmen give off what Barnes delicately terms a “defensive secretion. If they’re aggregated,” he notes, “that defensive secretion will be much stronger, to ward off predators.”

Which brings us back to bedbugs?

No. No, it doesn’t.

The 20th-century hill folks Randolph interviewed may have reasoned that since daddy longlegs stink like bedbugs, and bedbugs came from bats (also not true, by the way), longlegs must deposit bedbug eggs on bats.

Harvestmen move quite quickly, but even they aren’t swift enough to leap up and stash another creature’s eggs upon bats that are actively flitting about in search of women with big hairdos. So would they creep upon the sleeping bats in their big dank cave ...?

The very notion is spooky. Enough of that.

ActiveStyle, Pages 25 on 09/17/2012