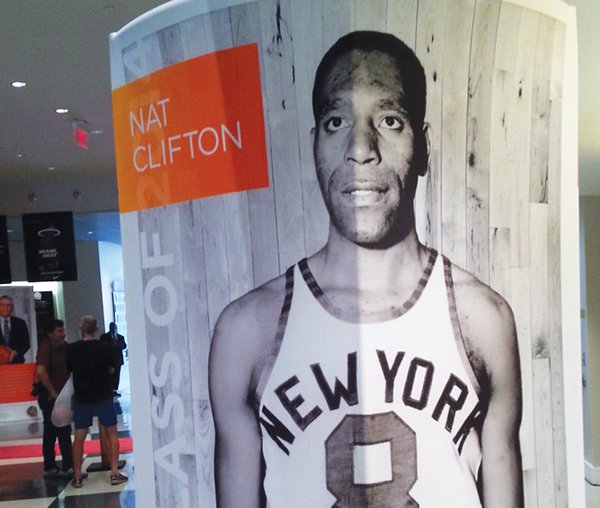

The annual Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame enshrinement ceremony two weeks ago was a star-studded affair as usual. Reporters and cameramen clustered around the tables of luminaries such as former NBA commissioner David Stern, all-star center Alonzo Mourning and guard Mitch Richmond. There was one table, though, only a few visitors passed by. It was dedicated to the memory of Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, one of the NBA’s first African-American stars, a New York Knicks centerpiece of the 1950s and, now, 24 years after his death, a Hall of Famer.

The central Arkansas native’s influence on basketball was as vast as his famously large hands. He set into motion a fundamental shift in the game’s style as one of the first big men to dazzle the NBA with dribbling ability and flair, occasionally employing a behind-the-back pass and even rolling passes down the court to evoke his Harlem Globetrotters past. At a time when there was only a handful of black players in the league, Sweetwater endured many racist taunts. According to a 1978 Chicago Metro News column, Sweetwater ended up in about six fights in his nine-year NBA career, usually in self defense.

“Sweetwater was a man at a time when that was not fully accepted,” Hall of Famer Bill Russell said on screen during the enshrinement ceremony. “That was the kind of image that the young black players needed.”

Hall of Famer Oscar Robertson shared a similar sentiment on video: “He was a pioneer for me and a lot of other African-Americans.”

Sweetwater is the subject and namesake of a major motion picture to be released next year that will star the likes of James Caan and Nathan Lane. Actor Wood Harris, well known for his part as Avon Barksdale in the HBO series The Wire, will play Sweetwater himself. Writer-director Martin Guigui, who has spent 18 years researching the film, said Sweetwater will focus on the year 1950, when Sweetwater became the first black player to sign with and then play for an NBA team. (Harold Hunter signed first but never played. Sweetwater followed Earl Lloyd as the second black player to see NBA action.)

The movie won’t delve into Sweetwater’s obscure roots in south Lonoke County, though.

Sweetwater was born Clifton Nathaniel Jr. in 1922 in a swampy area around England. His teenage mother and father had moved there from Georgia, likely for the promise of fertile land and the bounty it would provide. Jatuan Nathaniel, one of Sweetwater’s three children, says her father didn’t speak much about his early years. But he did tell her they were hard, filled with plenty of cotton picking.

A flood that devastated the Arkansas Delta in 1927 and signs of the upcoming Great Depression almost certainly damaged the dreams Sweetwater’s parents had for themselves and their children. In the 1920s Delta, according to an article by University of Arkansas historian Jeannie Whayne, “A shortage of labor should have made for greater opportunities for laborers — higher wages, better conditions — but, in fact, what they were to find in Arkansas was no different from what they left behind in Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee and Mississippi. That is, economic, legal and extralegal exploitation and, ultimately, severe limits on their ability to share in the bounty that Arkansas’ rich Delta promised.”

Arkansas historian Tom Dillard says the Nathaniels probably lacked electricity and had severely limited educational opportunities for their children. “Children were put into the fields quite early in their lives, so [Sweetwater] might have known field work — serving as a water carrier perhaps. Poor people of all races had trouble educating their children as they were needed for agricultural work.”

Life wasn’t totally bleak, though. It was in Arkansas that a young Sweetwater likely first fell in love with the taste of water mixed with sugar, which led to his well-known moniker. Later, he became a big fan of soft drinks, especially Coca-Cola, and he passed his fondness for sweets down to his kids. “It’s bad,” Jatuan says, chuckling. “We’re like cookie monsters.”

She recalls her father briefly lived in Little Rock, too, and that it was there that his older sisters had fun dressing him up in girls’ clothing. Around 1930, most of the family left Arkansas, with Sweetwater and his parents landing in Chicago’s South Side. Better economic and educational prospects prompted the move, as they did for hundreds of thousands of other blacks leaving the Delta for northern cities. From 1920 to 1930, the black population of Lonoke County dropped from 11,628 people (34.8 percent of the total population) to 10,917 (32.3 percent), according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2013, blacks represented 6.1 percent of the county’s total population.

In Chicago, Sweetwater developed into a star in basketball and 16-inch softball, a variant in which fielders don’t wear gloves. In high school, the local reporters requested he change his name because “Nathaniel” was too long for their newspaper accounts. He obliged, and in transposing his first and last names and shortening Nathaniel, he became known as “Nat Clifton” in the papers (though he would remain “Sweetwater” to friends). He grew to be 6-foot-7 and around 230 pounds, and he played football and boxed for fun. In the same 1978 Chicago Metro News account that chronicled his NBA fights, Sweetwater claimed that as a teen he’d fought Bob Satterfield, a renowned professional heavyweight boxer in the 1950s. “I used to whup him every morning before breakfast,” he told the columnist.

Sweetwater attended Xavier University in New Orleans and fought in World War II before playing professional baseball and basketball. In the late 1940s, he became one of the Globetrotters’ main attractions and was the sport’s highest-paid black player. He then helped lead the Knicks to three straight NBA Finals, often tallying a double-double (10-plus points and rebounds) despite having no plays called for him. He became an All-Star. In an article printed in the Hall of Fame enshrinement ceremony program, one teammate, Willie Naulls, recalled him as “gentle, compassionate and empathetic as anyone I met during my professional career.”

Yet Clifton was far from a pushover. How could he have been to survive in this era, where he and the other black pioneers sometimes had to secure separate sleeping quarters from white teammates when on the road? Bob Harris, a Boston Celtics center, found out the hard way one game after jawing with Sweetwater and landing a particularly hard elbow on him under the basket. According to the Chicago Metro News, Sweetwater “unleashed a left hook and a right cross, leaving the Celtic spread-eagled and unconscious on the floor for over 10 minutes.”

Sweetwater retired from the NBA in 1957, but until 1964 played for various professional traveling teams (including one headed by his former Globetrotter teammate “Goose” Tatum, a native of El Dorado) before working as a taxi driver in his old Chicago neighborhood. It’s likely he visited Arkansas a few times — and possibly even England, his hometown — with the Globetrotters and the spinoff teams with which he later barnstormed. One central Arkansas basketball player, Dave McPherson, recalled seeing Sweetwater visit Little Rock with a group of other Globetrotters for a game at what’s now the Dunbar Community Center.

There are still many unknowns regarding Sweetwater’s Arkansas ties, but more and more attention is being paid to the rest of his life. His Hall of Fame enshrinement helps, as will the forthcoming movie. For some people, these journeys of discovery take on a deeply personal meaning.

Clifton Nathaniel IV was born in 1991, the year after his grandfather Sweetwater died. Clifton never personally knew Sweetwater, and his father, also deceased, didn’t tell him much about his famous grandfather. But traveling to Springfield, Massachusetts, with his aunt Jatuan for the Hall of Fame ceremony gave Clifton the opportunity to connect with the memory of his grandfather through those who knew him. “I’m just glad I get to learn more about him,” Clifton says when receiving an enshrinement trophy on his grandfather’s behalf. “The only thing I knew was what I was told and what I researched myself. But I couldn’t find much about him.”

That’s finally changing.

UA’s Richardson also earns HOF induction

On the night of Aug. 8, Jatuan Nathaniel and Clifton Nathaniel IV walked onstage at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame enshrinement ceremony to honor Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, their father and grandfather and an African-American pioneer deemed by some as the “Jackie Robinson of the NBA.” After walking offstage to return to their seats, they stopped and leaned down to shake hands with another 2014 enshrinee: Nolan Richardson.

Richardson, a pioneer in his own right, had earlier that night told an audience filled with the likes of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird about his grandmother, who’d commanded him as a high schooler not to shy away from playing for Texas Western College (now the University of Texas at El Paso) because he would have to sleep in a different hotel than his white teammates. “‘You remember Jackie Robinson?’” he recalled her saying. “‘You remember what he did?’ I said, ‘Yes, ma’am.’ ‘You have to do the damn same thing!’”

“‘Crack of the door is all you need, son. You can take care of the rest all yourself. It’s all about attitude. Force your attitude on the people you deal with. Let them see through your eyes where you need to go.’”

Richardson went on to become head coach at Western Texas College in Snyder, Texas. In 1985, he was hired by the University of Arkansas as the first black head coach of a major college football or basketball program in the South. His Razorbacks won the 1994 NCAA national championship and went to three Final Fours. A host of Richardson’s relatives, friends and associates made the trip to Massachusetts to celebrate his big moment, including Little Rock attorney John Walker. Richardson credited former Arkansas athletic director Frank Broyles and Little Rock Judge Wendell Griffen as part of “the team that made me reach the dream.”

For wayyy more on Arkansas basketball, visit Evin's Sports Seer blog here.