Damien Chazelle, the talented 29-year-old writer/director of Whiplash would like to make something abundantly clear: While the film's story -- involving a young jazz drumming student in his first year at a prestigious New York music school who runs afoul of the hard-driving, relentless teacher who torments him -- is rooted in a certain amount of autobiography, the unconscionable tyrant teacher (played convincingly in the film by a harrowing J.K. Simmons) is not, in fact, directly based on his own hard-driving high school jazz teacher, except in one important respect: "I learned pretty quickly what it was like to be a musician dealing with fear on a daily basis," he says. "Up until then, drums had really been a pure hobby, never a source of dread or anxiety, and suddenly my skill set at the drums -- or lack thereof -- just became everything."

The truth is, in the long, storied history of jazz, there are plenty of other similarly hell-bent individuals from which to cull, as Chazelle points out. "The character really became a composite," he says. "There was a lot to play with, [many] jazz conductors famous for being really tough on their players, like Buddy Rich or Jerry James. There's a history in terms of borderline abusive behavior and cruelty. That's a whole side of the music I really wanted to showcase."

Whiplash stars the hang-dog-faced Miles Teller as Andrew, a drum prodigy with a slightly inflated ego, who encounters Terrence Fletcher (Simmons) one night early in the semester as he's working on his swing timing in the school studio. Fletcher, dressed entirely in black, puts him through his paces a bit before dismissively vanishing down the hallway. Thus is established the power paradigm between the two men: Andrew, wanting nothing more than to please this taskmaster, hoping to unlock his talent to become one of the greats; Fletcher, acutely aware of this, taking full advantage of the student's obsequiousness, to sadistically drive him into the ground. Beyond the brilliant performances by both actors, the film's power lies in this significant artistic dichotomy: In order to achieve greatness, one must put oneself through absolutely devastating rigors; and in order to survive them, one must give up on just about everything else in the process. Chazelle's question coming into the production was a simple one, "I wondered to what extent did the ends justify the means."

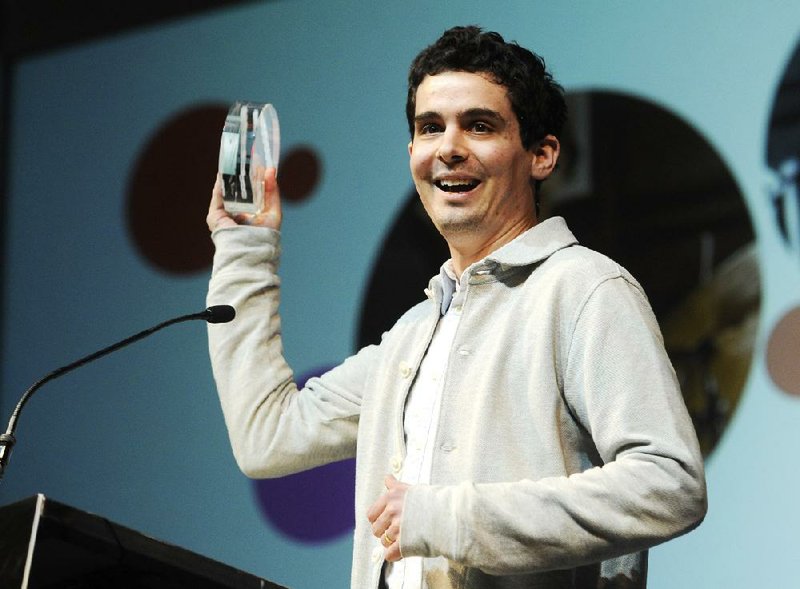

The resulting film, which absolutely dominated this year's Sundance festival, winning the Audience Award and the Grand Jury Prize, suddenly catapulted Chazelle into pretty rarefied air: a young director with a head of steam and bulging calendar of forthcoming projects (including his next film, a full-on musical set in Los Angeles called La La Land, also starring Teller). Still, he did his level best to keep this kind of literal overnight success from changing his outlook, and he hopes that the film can find a sympathetic audience outside what he termed the "festival bubble," although it's not without a certain amount of trepidation that he sends it out into the world at large. "I think it's a movie that plays for a crowd. Hopefully, it crosses through. But you never know. At the end of the day, you have to send your kid off to college, basically, and you hope that people show up."

One of the film's strong points is its emphasis on the nuts-and-bolts physicality of musicianship, the actual toll it takes on your body (blood-spattered drum heads and bandaged hands are the routine in Andrew's cloistered world), which was very much in Chazelle's plan.

"I wanted to make a movie about technique," he says, "that kind of hard work. There are a lot of movies about music or art in general, but they're about what you do after practice, your emotional engagement, and there's not enough focus paid to the raw grind, the hard work of just mastering rudiments and really developing an inner clock as a drummer."

With that in mind, finding an actor who could handle the emotional depths of the character -- Andrew starts out as genial and likable, but becomes less and less so, the deeper he delves into his music -- and the rigorous demands of playing jazz drums was absolute necessity, and in this, Chazelle got very lucky to find the up-and-coming Teller, who just so happened to have some experience behind a kit.

"The thing that really saved me was that Miles had been playing the drums himself since he was about 15, so he was a very quick study: We were able to accomplish with him in about three weeks what it probably would have taken three months with someone else. I was worried I was going to have to do a lot more cheating than I actually wound up having to do."

Helping sell the character and his obsession was the fact that Teller's face registers a rabidly intense concentration as he plays, a fact not at all lost on the filmmaker. "Oh God," Chazelle says with a laugh, "his drum faces are just amazing. There's stuff going on in his face that he's legitimately not conscious of, and that's what makes it feel real."

Not content to offer up a simple good vs. evil banality, Chazelle instead strove to show the complexities of his characters' motivations. If Andrew becomes more unlikable as the film progresses -- in one particularly scalding moment, he dumps his sweet girlfriend (played by Melissa Benoist) in heartless fashion -- it's clearly in service to the achievement of his art; as overbearing and cruel as Fletcher can be, he is also driving his students to accomplish beyond what many of them can even imagine for themselves. Our sympathies fly between the two men throughout the course of the narrative, but never more so than during the film's nerve-wracking climax in Carnegie Hall, a long scene in which Andrew finally confronts his tormentor, in musical terms, and will either soar into the air or drop like a stone.

If the stakes sound high for a film essentially about a young man trying to play the drums, you are perhaps not getting the full gist of what Chazelle is pursuing. One could make an apt comparison to fellow Harvard graduate Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan, another film about the high cost of artistic achievement; but you could also just as easily connect it with Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket, a movie, after all, about the process of shaping young men into killing machines for the Vietnam War, and the director would be in total agreement with you.

"Basically, any kind of movie that reflected what it felt like to me to be a drummer," he says, "in terms of what the environment felt like. There's that question of how far is too far."

And to that end, having a character push his way through the intense, physical severities of his craft in such a way speaks to the very nature of suffering for one's art, in whatever form that might take. It just so happens that Chazelle landed upon a discipline that is visually affecting. After all, unlike, say, having to film a novelist, or composer, sitting at his desk and cursing at himself, this kid pours his blood, sweat and considerable tears onto a very real physical manifestation, his drum kit. This, also, was in Chazelle's ultimate vision of the film. "There's something simple and physical and direct about it," he says. "Someone is hitting something and making a sound out of it. That's ultimately what it comes down to."

MovieStyle on 11/28/2014