I don't think of Denmark as a happy place, although I've never been. When I think of Denmark, I think of brooding princes and Lucinda Williams' song "Copenhagen," which is about hearing bad news from back home while you're off in a snowy foreign land. I think of Denmark and I think of suicide, which isn't fair because the Danes kill themselves at a rate lower than that of Americans or even Canadians. It's obvious I don't know squat about Denmark.

The latest by novelist Brock Clarke -- whose previous books Exley (2010) and An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England (2007) have been droll and tragic explorations of unhappiness -- isn't really set in Denmark, where the happy people live, although that's where it begins and ends.

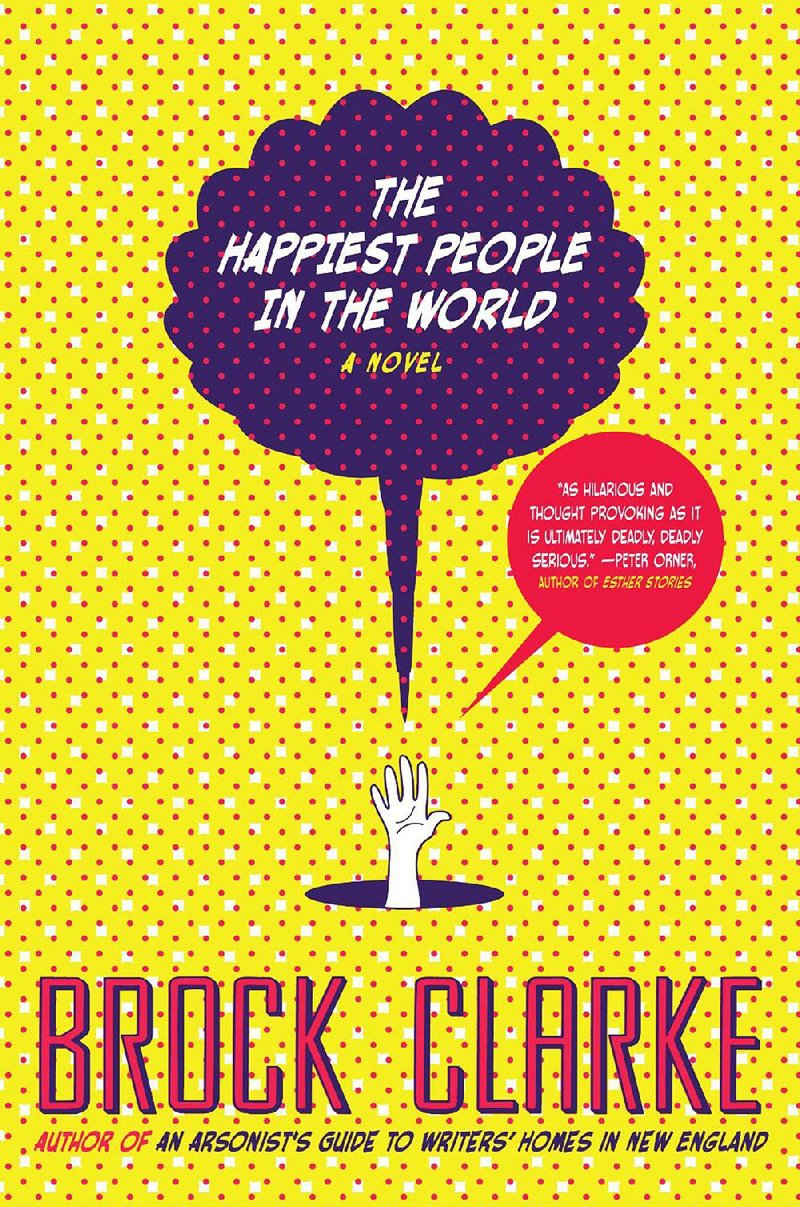

The Happiest People in the World (Algonquin, $24.95) is about a Dane who accidentally becomes an American, which makes him one of the truest kinds of Americans, and about the sorry world that forces the transition. It is both very funny and very sad, though I could understand how a person reading it might suddenly sit up and snap it closed and walk away and have nothing to do with it or Mr. Clarke ever again.

(Some people do not think Islamic terrorism, governmental surveillance of its citizens or near-universal gun ownership is all that funny. Some people are too unhappy to have much of a sense of humor.)

Jens Baedrup is a Danish political cartoonist working for a provincial newspaper in a smallish Danish city, an affable and not entirely untalented man who nevertheless seems (much like Clarke's previous protagonists) to be the sort of person to which things just happen. Case in point, in the aftermath of the famous outrage over the incendiary cartoon depictions of the Prophet Muhammad solicited and published by one of the country's leading newspapers -- Jyllands-Posten in 2005 -- Jens draws a response. This sort of hackish gesture does not seem to be a terribly big deal, except it enrages the son of a Turkish immigrant who is looking for something to rebel against. So he burns down Jens' home.

Though Jens is typically unflappable -- his motto is "everything is going to be just fine" -- Danish security agents cannot protect him from jihadists, so they fake his death. Enter a CIA agent called Locs, who manages to have Jens moved to her old upstate New York hometown, an unhappy place called Broomeville, to give her cover to try to reboot her relationship with the town's high school principal, Matty. (Though Locs calls him Matthew, she is so opposed to the diminutive that she calls the Motown legend Stephen Wonder.)

Locs supplies Jens with a new identity -- Hendrik Larsen from Sweden -- and prevails upon Matty to hire him as the school's new guidance counselor (a job apparently anyone can do). She sends him off on a bus to his new home and tells him not to worry, for "someone is always watching you in Broomeville."

This turns out to be literally true, as Broomeville is a town where everyone seems to be some sort of operative living a double- or triple-life. Jens/Hendrik fits in easily; he's a good listener and therefore a wonderful counselor or at least a marked improvement over his predecessor. True to his conviction that things will work out, he becomes involved with Matty's soon-to-be ex-wife.

Yet if Broomeville is a dystopian view of America, a place of weaponized gossips where murder is enacted casually, Clarke's satire retains a refreshingly light touch. Like the security camera fitted in the moose head above the bar of the local club, he unblinkingly observes unfolding absurdities, sketching with a few deft strokes the strivings of the duplicitous and the mean, heartbroken and thwarted townspeople. (Who are stand-ins for all of us -- all the lonely people looking to fill up their lives with something more.)

It is easy to find names to compare Clarke to -- he's a bit like Kurt Vonnegut in his matter-of-fact depictions of the surreal, a bit like Tom Robbins in his squirty plotting -- but I'm not sure those kinds of analogies are really fair to any of the writers involved. Clarke isn't telling us anything we don't already know, but his lectures are delightfully funny even when they relate uncomfortable truths. There is something violent and brutal about the American character, and the imperative to re-invent oneself does violence to those left behind.

I didn't realize until I sat down and started writing this exactly how deeply The Happiest People in the World cut me. It is sharp like that; it takes a while for your brain to register the sting.

...

Sonny Burgess is one of the few first-generation rock 'n' rollers still plying his trade, a rockabilly original who still occasionally surfaces to play live. He celebrated his 85th birthday in June with a show at Little Rock's Ron Robinson Theater, where he was joined by Bonnie Montgomery, Ronnie Block, Kevin Kerby and members of the Salty Dogs. He's a venerable figure, a member of the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, and Marvin Schwartz's biography We Wanna Boogie: The Rockabilly Roots of Sonny Burgess and the Pacers (Butler Center Books, $39.95) is as overdue as it is exhaustive.

The title is slightly misleading -- the book is more a work of history than criticism or cultural anthropology. The referenced "roots" have more to do with Burgess' upbringing in eastern Arkansas than with the feral music he still produces, but Schwartz has done an invaluable service to those interested in the once vibrant roadhouse milieu of what has been officially designated as Arkansas Rock 'n' Roll Highway 67.

Relying heavily on interviews with Burgess and other primary sources, We Wanna Boogie is a work of academic rigor that remains highly accessible. And it's loaded with great photographs.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 11/30/2014