Fifth in a series

BIG BEND RANCH STATE PARK, Texas -- As he plowed through nearly impenetrable cactus, Rick remained focused on a serrated ridge in the distance.

He felt sure he would find me in the valley beneath its rocky outcroppings.

Alone in Texas’ vast desert, Cathy Frye clung to life and her memories of home.

"Wait! Wait!" yelled park Superintendent Barrett Durst, jogging to catch up.

Rick kept going. "I'm going to find her," he called over his shoulder. "I'm going to bring her back."

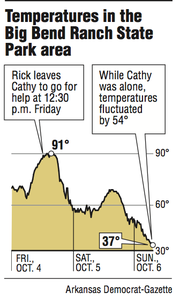

It was Saturday morning, Oct. 5. Rick had left me under a mesquite tree nearly 24 hours earlier and, after a grueling hike, made it back to the ranger station to summon help. Twelve volunteers had spent the night looking for me. A helicopter with a searchlight remained in the air for several hours, but the pilot never spotted me.

After three days and two nights lost in the desert, Rick had been too weak to join the all-night search. But when the rescue effort resumed at sunrise, he felt re-energized and optimistic. The number of searchers had doubled, and Rick felt certain he could lead them to me.

Rick and Durst spent the next several hours trying to retrace Rick's path to where we had separated the day before.

"There's my rock," Rick said, spotting one of the boulders where he'd sought shade. His hiking-boot prints were still visible.

Durst entered the coordinates on his GPS unit, and the two men continued backtracking.

Rick looked for landmarks he'd noted the day before. In particular, he searched for a pair of boulders near the mesquite tree where he had left me.

But nothing looked familiar, and Rick grew increasingly frustrated.

Where is she? Why can't I remember?

Hallucinations

After a night of vivid hallucinations, I awoke Saturday morning convinced that I'd been spotted by the helicopter.

I eagerly awaited the arrival of my rescuers. But no one showed.

I also believed that Rick had returned and was sleeping somewhere near my tree. I couldn't see him, but I knew he was there.

"Rick? Where is everyone?" I asked. "Rick?"

Why won't he answer me?

My tortured mind came up with a new theory to explain the absence of rescuers: Rick and my parents were drinking coffee at a campsite behind the rock formation that towered in front of me. They wanted me to go to them.

Don't they know I can't get there by myself?

"Mom! Dad! Rick! I can't walk!" I yelled over and over. "Where are you? I need someone to carry me!"

In another vision, imaginary people told me to walk up to a lodge on top of the rock formation. There, I could take a shower and one of the park employees would drive me to the newsroom parking lot, where I'd left my car.

I scooted out from under the tree, propped myself up on my elbows and tried several times to stand, but couldn't. The sudden exposure to sunlight hurt my eyes. I slid back under the tree.

I'll just stay here. Someone will come and get me.

After days of hiking under the desert sun, I thought of my tree as a refuge. And it remained symbolic of the promise I had made to my husband.

"I will wait for you," I'd said, and those words had rooted me underneath the prickly, scraggly branches.

But, while the mesquite protected me, it also thwarted searchers' efforts to find me.

My head and torso were shrouded by the tree's low-hanging branches. And my legs and feet, coated in dirt, blended perfectly with the desert floor.

More manpower

Lt. Kenneth "Doc" Watson knew I didn't have much time left.

Additional game wardens already had been deployed to help with the search. But Watson, who is part of the Texas State Park Police, had a specific man in mind for this mission: Fernie Rincon.

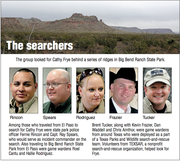

Rincon is a soft-spoken park police officer based at Franklin Mountains State Park in El Paso. He's well-known throughout West Texas for his ability to find lost people. Watson wanted him involved ASAP.

But each time Watson got Rincon on the phone, the cell signal cut out.

Finally, Watson threw down his phone in frustration. "Forget it," he said.

His wife looked at him reprovingly. "Do you really want to do this without Fernie?"

So Watson tried again, and within an hour, Rincon was on his way to Big Bend. So were two El Paso County game wardens: Roel Cantu and Hallie Rodriguez.

Rodriguez was especially eager to help. In 2010, a Texas Parks & Wildlife plane went down in the Franklin Mountains. Rodriguez was one of three people onboard. The other game warden and pilot managed to get out of the wreckage and call 911. But Rodriguez remained trapped for three hours. She knew how it felt to be helpless in the wild.

As Rodriguez, Rincon and Cantu headed toward the state park, four game wardens from different areas of Texas also were being deployed.

The four -- Brent Tucker, Kevin Frazier, Dan Waddell and Chris Amthor -- belonged to a newly formed statewide search-and-rescue team for Texas Parks & Wildlife.

That Saturday morning, Frazier was out working with deer hunters in Seguin -- 530 miles away from Big Bend -- when his phone rang.

"Saddle up," his captain said. "You're going to West Texas."

Just two weeks earlier, Frazier and other team members had participated in their first training course.

This would be their first mission. And it would take place in the harshest landscape that Texas has to offer.

'Where is she?'

By late afternoon, Tucker, Rodriguez and Cantu had arrived at the park. They went immediately to the cottonwoods and spring where Rick and I had spent Thursday night. Maybe, they theorized, I had returned there for more water.

They found only the footprints Rick and I had made two days earlier.

That evening, Capt. Ray Spears drove in from El Paso. The gregarious Spears is a longtime lawman who spent the past 20 years as a police officer, deputy and game warden. On this occasion, he would serve as incident commander.

Spears set up a command post at the state park's bunkhouse. The only landline was in the commercial kitchen. It connected Spears to his bosses. A satellite phone in his truck was Spears' only means of staying in touch with the search teams under his command.

Spears spent much of Saturday evening running between the bunkhouse kitchen and his pickup. In the kitchen, he stretched the phone cord into the pantry and scribbled notes on a cardboard green bean carton. In his truck, he waved his arms wildly each time he lost contact with a search team.

At 8 p.m., after a nine-hour drive, game wardens Frazier and Waddell turned onto the 27-mile gravel road that led to the park's headquarters.

Frazier admired the breathtaking landscape while shooting video with his phone. But he also recognized the desert as a formidable opponent.

Beautiful. But challenging.

More visions

When my wedding ring fell off my shriveled finger, I listlessly groped the twigs and rocks within reach.

Nothing.

The desert had already taken so much from me -- the use of my legs, the rational part of my mind, my husband.

Now it had my ring, too.

I spent most of Saturday rolling around under my mesquite tree, trying to avoid the rays of sunlight that penetrated its foliage.

I had grown used to the monotonous buzz of the helicopter overhead. I knew it was there because of me, but I no longer understood why. And I recalled only vaguely that Rick had gone in search of help.

Once, when the helicopter sounded especially close, I slid out from under the tree. I giggled about "mooning" the pilot.

As the heat intensified, so did my hallucinations.

The mesquite tree became a shotgun house in the country, where the kids and I sat on the front porch and shared family legends and stories.

Another hallucination featured the Wind Women, who showed me how they could summon and control the wind. One of these women was my ancestor. Each time the helicopter drew near, the increasing volume of its spinning blades became "wind" that had been "captured" by my ancestor.

I watched dreamily as the helicopter flew directly over the ravine where I lay. It was controlled by a Wind Woman who had one foot on each of its skids and reins in her hand. This time, I didn't yell or try to move. Flagging down the helicopter would violate the Wind Women's trust.

I spent Saturday evening as a teenage boy whose parents had gone out of town. They'd left me with an elderly neighbor who let me skip school to watch movies.

The next round of hallucinations cast me in the role of baby sitter. Our neighbors down the street left town and asked me to take care of their son, who had suddenly developed a physical disability.

In reality, the "son" was me, struggling to move arms and legs that no longer worked. I remember trying to lift one of my legs with my hands, to no avail. I mentally chastised the parents for not doing more to assist their son. Why wouldn't they let him use crutches?

A cold front moved in when darkness fell. Temperatures dropped into the upper 30s.

I wore only a tank top by this point. I'd never put my hiking shoes or socks back on after using them to block the sun and to serve as "pillows." My shorts still hung in the tree's branches.

Bitterly cold, I curled up under the tree, shivering convulsively.

My hallucinations incorporated the change in weather. In one, my daughter was supposed to have signed us up for a school trip to Mississippi. Instead, Amanda had put us down for an expedition to Wisconsin. I'd packed for Mississippi, so now we were unprepared for the Wisconsin cold.

"Why did you change our plans?" I asked my daughter. "We're not dressed for this!"

My reality quickly shifted again. This time, I had promised to travel to Missouri to baby-sit a friend's children so that she and her husband could attend a Bon Jovi concert. But I canceled because I didn't want to get out in the cold.

I also turned down a request to help another friend throw a last-minute birthday party for her little girl.

I kept yelling at people to quit calling me on the phone. Didn't they understand that it was too cold to leave the house?

I scratched and clawed at the dirt, instinctively trying to burrow for shelter. My hands, arms, feet and legs went numb as my body channeled blood to its core to protect vital organs.

And then, suddenly, I felt unbearably hot.

The muscles responsible for contracting my blood vessels had tired out and relaxed, sending a rush of blood to my extremities. Also, the part of my brain that regulates body temperature had begun to malfunction.

Desperate to quell the hot flash, I took off my tank top.

I spent the rest of the night naked.

Interrogation

After the search was called off for the night, Rick sat in the bunkhouse, watching the flurry of activity around him. New arrivals set up cots and unrolled sleeping bags. When the bunkhouse got too full, people started pitching tents outside.

Tucker, Spears and Watson wanted to interview Rick. They harbored a grim suspicion that he might have killed me and concocted the lost-in-the-desert story to cover his crime.

Rick knew the interview was coming. In preparation, he downloaded to his laptop the photos he'd taken during our 2½ days together in the desert.

At 9 p.m., Spears, Watson and Tucker escorted Rick to the ranger station. They used multiple interrogation techniques to evaluate his credibility. They deliberately inserted errors. They asked Rick to tell the story in reverse.

When Rick said he'd left a knife with me so that I could cut up cactus to eat, Tucker was skeptical. Sure you left the knife -- covered with blood and buried under a rock.

About 45 minutes into a 2½-hour interview, Spears ruled out Rick as a killer. Still, the three men pressed him for more details, hoping to elicit a clue to my whereabouts.

The group looked at a series of three steep ridges on a topographical map. Rick said he'd left me behind the first one.

"The time frame just doesn't fit," Tucker told him. "That's way too long in between from where you left her to where you saw that vehicle at 6:30."

"What color was her shirt?" Tucker pressed.

"I can show you a picture," Rick offered.

"You have a picture of what she was wearing?"

"Well, yeah. I shot a picture everywhere we spent the night and of her coming out of the canyon Friday morning."

"Can we see them?"

The three lawmen gathered around the computer, pausing the slideshow every few minutes so that they could take photos with their phones.

The interview ended at 11:30 p.m. As the men parted ways, Watson watched Rick walk back to the bunkhouse.

"He's tired, he's had no sleep, but he still takes long strides," Watson said to the others. "He walked more than he thinks he did."

Tucker and Spears agreed.

The three men followed Rick back to the bunkhouse, where they set up the computer so that all of the searchers could see the photos. They also expanded the search area to include two ridges behind the one Rick had pointed out.

Tucker pulled out a map and drew a circle that encompassed all three of the ridges.

He tapped the last one with his pen.

"That's where she is."

Sunday, Oct. 6

The next morning, I awoke in a pool of sunshine.

For four days, I'd hidden from the sun. While I no longer understood why, I knew on a deep, primitive level that direct sunlight spelled danger.

When did I crawl out from under the tree?

I managed to get my head and torso wedged underneath the mesquite. But I was too weak to curl around its trunk like before. I could feel the sun burning my legs.

Stupid. So stupid to have done that. It's so hot.

My entire body shook with tremors. Still, I felt too hot.

It seemed I had always lived this way -- too hot or too cold. The needles embedded in my torso and legs had always been there. I had even grown used to the unrelenting thirst. Water was part of an increasingly hazy past, along with memories of my husband and children.

I belonged to the desert now. Maybe forever.

Tomorrow: A frantic search as death nears

SundayMonday on 10/16/2014