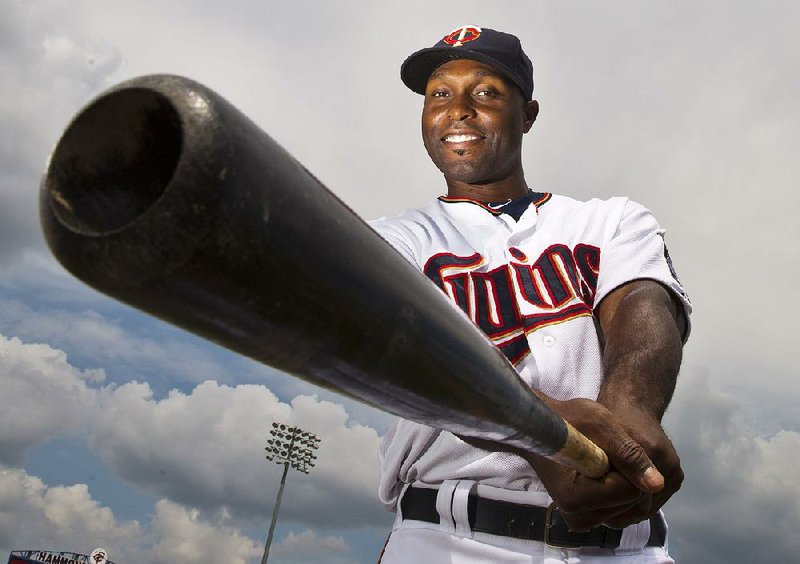

PROSPER, Texas -- If ever there was an appropriate place for Torii Hunter to land, it's here. The all-star outfielder who, in his 17th season, still musters the skills to merit $10.5 million from the Minnesota Twins this year, has had about as prosperous a life as the son of a schoolteacher and a drug-addicted electrician in Pine Bluff could imagine.

"You know, the world says, 'Hey, make millions of dollars. Do something that nobody can ever do.' I would say ... that's not success. You're still unhappy."

Date and place of birth: July 18, 1975, in Pine Bluff

Family: wife Katrina, and sons Darius McClinton-Hunter, Torii Hunter Jr., Monshadrik “Money” Hunter

Nickname: Spiderman

My first car was an Explorer, Eddie Bauer edition, when I got drafted.

My greatest shining moment on the field was robbing a home run from Barry Bonds in the 2002 All-Star game in Milwaukee. All of the nation is watching, all of Arkansas is watching. He hits the ball, the best hitter in the game, the best hitter I’ve ever seen. Hits the ball, but he didn’t hit it far enough. Sorry ’bout it!

I could eat french fries all day.

Exercise I hate the most: Legs, anything legs — lunges, squats, leg presses

The household chore I just don’t want to do is washing clothes.

A scent that makes me nostalgic is the International Paper mill. It reminds me why I left that area in Pine Bluff.

Fantasy dinner guests: Jesus Christ, Albert Einstein and Jackie Robinson. I would like to know what he really went through.

My all-time favorite movies: Coming to America and Friday

The coolest guy I ever played with was maybe David Ortiz. He was the funniest guy.

My favorite musician is Prince.

The thing I appreciate more and more about my wife is the support she gives me. She’s always there to hold me up and make me better.

My first job was a paper route.

When it’s all over, I will be in business, sports analysis, and supporting my family, trying to make up for lost time.

One word to sum me up: Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious

Hunter is happy, riches and fame notwithstanding. His kids are in college, he says, and he's growing older with his wife, and they recently welcomed a grandchild. He's fit -- paleo diet -- and rooted and doing "my Lord's work."

Would the money untangle from the happiness? The Hunters, Torii and Katrina, have a mansion with a full-size indoor basketball court and a home theater and a pond big enough for a boat ramp and a docked pontoon. One of their neighbors is Deion Sanders. Do they ever knock on Deion's door and ask for a cup of sugar? No, it's not like that! You can't see the door from his gates.

Their generosity has played a big part in the expansion at New Life Community Church in Frisco where they're a chartering family. It has grown from two dozen families to about a thousand members. In 2007, the flock squeezed into a 1,500-square-foot worship space that, summers, would hit mid-80s indoors even with air conditioning. Since that time, and in largest part because of the Hunters, the church enjoyed two separate 20,000-square-foot expansions.

"We couldn't have done this this fast without the Hunters," says the Rev. James Hutchins, "but let me say this. ... Biblically, we believe Christians are supposed to give, but if you're going to give with an expectation, please don't give. I'm not that kind of pastor."

Hunter himself made that a condition of the gift, Hutchins says. That "'You'll never have to worry about me telling you how to pastor this church.'" Meantime, Katrina Hunter has mopped floors and taken out trash. Torii has collected chairs after meetings. Neither enjoys reserved seats, and in fact, they typically sit in back.

Back at the manse, inside a game room the ballplayer calls Torii's Tavern, are a bunch of his Gold Gloves and two Silver Slugger bats. There's a Fender electric guitar signed by the members of Guns N' Roses and memorabilia signed by dozens of eminent athletes such as Muhammad Ali. A nearby bathroom features a sauna and a black porcelain urinal and is ruled by what he calls "man law" (as opposed to "woman law," which governs the rest of the house). Back in the Tavern, his All-Star game jersey -- the one he wore when he reached over the center-field wall and snagged a Barry Bonds home run -- hangs on the wall. There's another jersey there, too -- Andre Dawson's.

Remember him? Dawson's "the reason I play baseball." In 1987 the outfielder hit 49 home runs, "and my granddad, when I walked home from [Indiana Street School that fall], my granddad would make me sit on the couch and watch the last six innings of the Cubs game on WGN, and every day it seemed like he hit a homer."

Dawson had a Jheri curl, so Hunter got one. Dawson leaned back in his batting stance and presented a stiff front leg, as did Hunter, after some adjustment. "I wanted to throw like him, I wanted to be like him. So, this guy inspired me. I told him this years later."

Now, when Hunter's in south Florida, the Hall of Famer seeks him out, Hunter says. It's an incredible thing, this friendship. "That's why I tell athletes, you are an influence on these kids. Because I was one of them who was influenced, so, thank you, Andre."

Hunter has never had a year as special as Dawson's in 1987, but it may be that he has brought about that kind of inspiration off the field. The Hunters have given hundreds of thousands of dollars for a baseball complex in his hometown (at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff). This summer the city hosts a Babe Ruth League World Series, and businessman Bill Jones hopes capital construction will be largely finished by then.

His foundation, The Torii Hunter Project (in partnership with the national Heart of a Champion nonprofit), has put a million dollars behind educational curriculum, college scholarships, family assistance, wellness programs and other community support, specifically in Pine Bluff, Southern California, Detroit and Minnesota.

Heart of a Champion is a character education curriculum that aims to help school-age kids learn core character traits such as responsibility, respect, self-control and compassion.

"A lot of these kids don't know what responsibility is. They've heard of it, but they've never seen the act," he says, and here he can clearly put himself in their shoes, "'Yeah, I've heard of responsibility, I just don't know anyone in my family who's responsible.' ... If a dad doesn't take care of his family, then how's [a kid] gonna know responsibility unless he gets redeemed by someone else?"

Hunter says his dad has battled addiction since he, Hunter, was a kid. "It was tough growing up knowing that your dad was on drugs and everybody else knowing it as well," but his Bible tells him there are the rich and the poor of spirit, and his dad is poor. So he supports him with encouraging text messages and a certain stewardship his wealth affords him. Because his Bible also tells him "Gotta treat those parents fairly for your days to be long."

In February, the Hunters hosted a big Super Bowl party, and Dad was there. "He's still a great man -- fun, funny -- he's just still fighting demons."

So was Basil Shabazz.

No story about Hunter is complete without Shabazz, because they're boyhood mates, and because, as teenagers, one was an athlete of almost mythical abilities, and the other was Torii Hunter. Amid the lore, Shabazz could dunk a basketball at the age of 12 (he was not and is not particularly tall) and was drafted by a professional baseball team after playing only his senior year (he had played organized baseball before that, just not for his high school).

"I mean, he was the No. 1 prospect for the St. Louis Cardinals. You cannot be the No. 1 prospect when you haven't played organized baseball but one year."

In 1994, during the off-season, Hunter and Shabazz were in Conway late one night when a police officer discovered a handgun and a small amount of drugs in Hunter's Ford Explorer. The two were charged with misdemeanors. The Twins stood by their top prospect but the Cardinals released Shabazz the next day. He tried to get back into football at UAPB but suffered a neck injury that ended the comeback.

Shabazz, incidentally, is Hunter's example of success -- lower-case S. Today, he's a youth coach in the Dallas area and the head of a thriving family. He is the "success" Hunter was framing up in the beginning.

A LIFE EXPERIENCE

By any standard, Hunter is a capital S success. It's harder, then, to believe that the cloth he's cut from wouldn't be different without the money and stature, but two things seem sure. One is that he would be a vocal Christian and social conservative, and the other is that he sees life, especially early life, as a quest for "life experiences."

From the podium in the Grand Hall of the Governor's Mansion on Jan. 29, at Homeruns and Heroes, a fundraiser for the Torii Hunter Baseball, Softball and Little League Complex in Pine Bluff, he thanked first Jesus Christ, "my Lord and savior." Next, before the 200 or so fans -- some Little League kids -- he thanked his mom this way, "My mom, Shirley? A lot of beat downs. Kids? Whuppin's work. Just telling you. It works. Can't go in the corner."

At the same event, he said to the married men, "your woman is your rib -- believe that!"

And about the governor, whom Hunter did a TV spot for, he says, "What we need in this state are jobs, a different mindset as far as schools, and he has great values and morals."

Is he -- gasp -- a Republican? No! He says, sincerely, but look -- he eschews individualism ("we always talk about team"), bristles at division ("separated we fall"), opposes same-sex marriage and disdains taxes. "Because of what I'm making ... I'm a Republican." (In fact, he moved to Texas largely because it hasn't a personal income tax.)

Hunter loves this century, the fashion, the technology, the fitness advancements -- he has a hyperbaric chamber in his exercise room -- but he's pretty old fashioned. The household chore he hates most is washing his own clothes (he doesn't), and his wife wakes with him -- that's pre-6 a.m. -- to prepare his breakfast (at least in the off-season).

While the rest of the world would attribute his success to his gifts, he says it's really the accumulation of the right "life experiences."

"Success," he opines, "is a lot of little things done well," and each one improves the reality of future successes.

When he was little, baseball was second to football, but at 13 he had the chance to play in a Little League tournament in New Mexico. It was his first time out of the state, his first flight over his hometown -- from the air, the tesselated landscape of farm fields was an early lesson in three dimensionality. He stayed with a host family that made weekend breakfasts of "pancakes with syrup and eggs and bacon." They blessed the food. They went bowling. They went hiking in the mountains. "We didn't 'hike' in Pine Bluff!"

He hit a game-winning home run, and there were reporters who wanted an interview.

"Life experiences," he says.

Much of Hunter's philanthropy today is aimed at manufacturing such memories for kids in Los Angeles and Detroit and Pine Bluff because, until that plane ride, that multicourse meal, hotel amenities or a perfect shining moment, "you're there, where you are, and only there. You think that's it.

"You think that one way is the only way it's supposed to be. When you go and see something else, see it's a different way that you can live your life, you're like, 'Wow!'"

BIG LEAGUE WORRIES

Hunter was drafted by the Twins with the 20th pick in the 1993 draft, but as the mid-1990s ground on, he found himself wondering if he would never graduate from minor league development. A husband and a father by then, he was contacted by friends and distant family who knew he was a pro but not that, as a minor leaguer, his salary was little better than a gym teacher's. He saved money he made playing for the AA New Britain, Conn., Rock Cats by sleeping in his car during home stands (road trips brought hotel relief).

"Everybody in my hometown, they say 'Torii's playing for the Minnesota Twins,' so they automatically thought you were making hundreds of thousands of dollars or even millions of dollars. To tell somebody you're making $287 every two weeks, they called you a liar. 'You're lying. You just don't want to help me.' I called people to try and help me, and they said, 'You don't need any help.'

"I realized then that I didn't want to borrow anything from anybody."

Here's the breakthrough that ultimately won him center field in the Bigs. Since his first minor league game, he'd been seeing a pitch "with a dot in the middle." He'd never seen a slider. At 18, in spring camp, his locker between Kirby Puckett's and Dave Winfield's, he'd ask about the pitch with the dot. Until then, "I just go by athletic ability -- I see it and I just hit it."

But, "Oh my God, that pitch is nasty!" It whips off the fingers like a fastball then "parachutes" down. Coach Jim Dwyer fed him hundreds, thousands of sliders. So in 1997 "we were talking, and I said, 'You know what? The slider that's down and away is hard to hit.' He showed me a video: Every major league player that tried to swing at the slider low and away could not hit it. 'Ain't no secret to hitting this slider! You just have to get it up. If it's low, let it go. If it's high, let it fly.'"

"Torii, he got rushed to the big leagues, he got there at a very young age," Dwyer says.

Here's what separates major league hitters from promising athletes and even stars in other sports, Dwyer says -- can you handle failure? "Because there's a whole lot of failure in baseball. And you gotta learn how to deal with it because I don't care how good you are you're going to fail 70 percent of the time as a hitter."

"It's easy after you've hit a home run, but after you've struck out four or five times in a row, people go soft."

In 1997 Hunter got to The Dance. He played a single game, entering as a pinch runner without an at-bat. But he'd turned a corner. Yes, he was developing into a big-league player. He was mostly finished second-guessing his fate.

And the trick to hitting the slider was often to let it go.

LET GO QUICKER

The trick to not striking out? Play the entire at-bat. "It took me a while to realize that."

Early, if he didn't like a called first strike, he'd fume. Here, he re-enacts an entire at-bat: "An umpire might make a bad call. I know for a fact it's a ball -- everybody knows it's a ball, but he calls out, strike one! You're like, 'Aw! Man!' Next pitch, boom, strike two! 'Aw, man, I can't believe' -- boom, strike three! You just struck out because you already struck out on the first pitch because you were so caught up."

Today, he breathes, he resets, he steps back into the box like it's a clean count.

His baseball mantras read like a Buddhist checklist.

"Be patient."

"Accept failure."

"Accept bad calls because he's human."

"And let go quicker!"

"Do not get caught up in anger."

He was not always like this, says his pastor, but like his coaches, Hutchins has found Hunter takes to instruction. "He's allowed me to mentor him," says the pastor, a 52-year-old military retiree, "but I had to earn it, and I had to earn it by not being impressed with his money, and treating his family like family.

"Because everyone else treats them like they're this entity, they're this thing. They get [from us] this place to say, 'We're just people from Pine Bluff, Arkansas. We have issues, our family has issues. We just happen to make more money, but at the end of the day, we bleed red.'"

High Profile on 04/05/2015