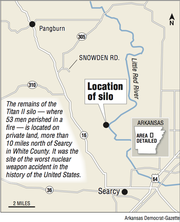

WHITE COUNTY -- Directions to the site of the worst nuclear weapon accident in the history of the U.S. are hard to come by.

A teenage convenience-store clerk had never heard the tale.

A cattle rancher said he thought it was "over on Clay Road."

A utility worker said to look for a boatyard right before Arkansas 305, then turn left.

Leaning against a red Chevy pickup in front of Pangburn Cafe, three middle-aged men squinted, one shrugged in bewilderment and another tilted his head to the left then his eyes widened.

"Do you mean the place where all those men died?" he asked. He grimaced, looked down and paused. "That was a sad day around here."

He didn't want to give his name. He was just a kid back then, he explained.

"I don't remember anything anyway," he said.

The site itself -- about 11 miles north of Searcy on a dead-end road off Arkansas 305, past a cattle guard and a "No Trespassing" sign -- is unremarkable. A concrete slab sits among waist-high prairie grass. Broken, rusted steel pipes jut from the ground. A tree shoots up between a crack in the concrete foundation. Stagnant green ponds stand cater-corner.

The new growth and leveled ground barely whisper of the searing tragedy that happened 50 years ago.

On Aug. 9, 1965, 55 civilian men returned from lunch to missile silo 373-4. By 1:10 p.m. 53 were dead.

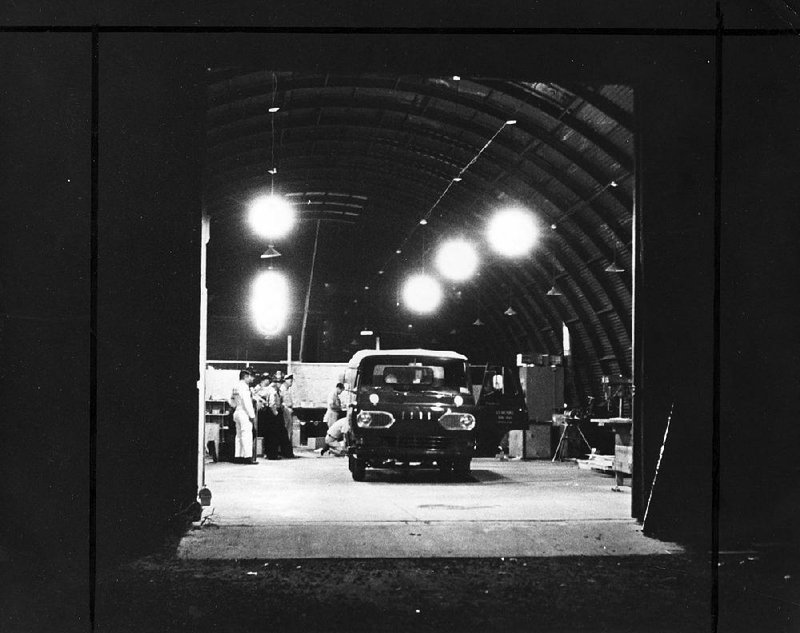

At the height of the Cold War, the government had hired contractors to shore up the strength of the silo that was cradling one of 18 Titan II missiles in the state. The contractors were welding blast doors, improving the hydraulic system and installing lighting to make the intercontinental ballistic missile less likely to be compromised in a nuclear attack.

Arkansas was one of four states -- the others were Arizona, Kansas and California -- that housed the 63 Titan II nuclear weapons. Each 340,000-pound missile was 103 feet tall and 10 feet in diameter, and was housed nine stories underground.

The 373-4 near Searcy was fully loaded with 150 tons of liquid fuel -- Aerozine 50, a mixture of hydrazine, dinitrogen tetroxide, and unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine -- that is 78 percent oxygen.

The silo was covered at ground level by a 750-ton door that moved laterally on rails. It was closed the day of the accident.

It was Gary Lay's first day on the job at the silo. He was 17, looking forward to playing football at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville after he graduated from high school.

"I had been working at the very bottom all morning, then came out for lunch," Lay, now 67, said Friday. "I stopped on the way back to talk with four or five other guys. We were right behind the gun barrel where the missile was."

Suddenly, Lay heard a loud "whoosh," an intake of air much like a gas stove lighting.

A flash rose from the floor to the ceiling.

The lights went out.

Nine stories, and 55 men in pitch blackness.

Smoke filled the silo.

Another flash.

Men screamed and stampeded away from the fire -- in complete darkness because of the smoke, clawing and climbing over one another on the emergency ladder.

Dozens fell to the bottom.

Another flash.

"My first instinct was to get away from the fire. I think God told me, 'Hey, you're going the wrong way.' There was no explosion. It was a blaze," Lay said.

Klaxons, sensors that the military officers wore on their belts, were screeching.

Climbing down toward the fire, Lay crept in the smoke-filled darkness, feeling his way along the wall. He made it to a horizontal passageway that led to the airmen-staffed underground control center. Lay had second- and third-degree burns.

It was there that he saw Hubert Saunders, who had been painting in the top level of the silo, 15 feet from the ground above. Saunders had escaped by holding his breath as he crawled on his hands and knees along a cable tunnel.

Saunders and Lay were rushed by ambulance to the Searcy hospital. Medical staffs prepared for massive numbers of casualties, but no one else arrived.

Saunders and Lay were the only survivors.

The other 53 civilians suffocated within seconds when the smoke -- sealed in by the 750-ton door -- sucked all of the oxygen out of the silo.

"I know it doesn't make it any better, but I think it's important for the families to know that their loved ones didn't suffer," Lay said. "It was a bad moment for 40 seconds, and then it was over."

The Air Force's final investigative findings concluded that the fire started when a welder nicked a high-pressure hydraulic line on Level 2 of the silo. Lay testified at hearings in Washington, D.C., that nobody was welding on level 2 that day.

Lay believes wires shorted out, sparking the flames.

Retired Air Force Col. Jimmie Gray -- who had worked with nuclear weapons for 27 years and curated a display on the 1965 disaster at the Jacksonville Museum of Military History -- said the Air Force proved conclusively that it was the welder's human error that caused the tragedy.

In fact, 52 people died from asphyxiation, and one -- the welder -- drowned in hydraulic fluid, he added.

"The hydraulic fluid went into his lungs and killed him," Gray said.

The fire burned for less than an hour, but more than 12 hours later smoke continued to billow inside the silo.

"They said they found bodies still on the ladders," Lynn Hamilton, president and general manager of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, said Wednesday.

The then-18-year-old Hamilton was picking cantaloupes with a group of teenage boys near Huron, Calif., when his parents told him that his brother, Archie Hamilton, 34, had died in the fire.

"We drove from California to Arkansas the next day," Hamilton said. "I remember just an overwhelming grief that his widow, who was a young woman, and his children were experiencing. And my mother. My mother was a real stoic person who never showed emotion. I saw her break down and cry. I had never seen that before in my life. It made an impact on me."

Hamilton's parents, who had just suffered the death of a granddaughter only months earlier, did not talk much about the accident in the years that followed.

"Our family, my parents, had suffered a lot of tragedy. They were raised in a real backwoods upbringing. It was a different time with lots of death and illnesses," Hamilton said. "By the 1960s most of society had moved away from that. It wasn't such a hard life for people. But this was just more of the same for my parents, and they stood up to it really well. They did not show a whole lot of emotion. I suppose that's not entirely healthy, but I suppose that's how they dealt with it."

Deborah Ritschel was 2 years old when her father, Charles McMahon, perished in the fire. Her mother, Evelyn Smith, didn't talk about the accident as Ritschel was growing up.

"My brothers were instructed not to talk about it too much," she said. "There were no pictures on the walls. When my mom was gone, I would sneak in to look at old pictures she had hidden away."

In her 20s, Ritschel, now 52, searched through newspapers and began seeking out family members of other survivors. At 32, she traveled from her home in Stockton, Mo., to see a memorial that had been moved to the Little Rock Air Force Base. She took her children on subsequent trips and tells them stories about their grandfather.

On Friday, she met her brother, Michael McMahon, 59, in Jacksonville to tour the museum exhibit, which is where the memorial currently rests.

"We told my mother we were coming down to visit the site," Ritschel said. "She didn't really have a reaction. She wasn't upset. She just files that away as trauma to never be thought of again."

Her oldest brother, Charles McMahon Jr., 62, of New Orleans, has not been back to Arkansas. He was 12 at the time of the accident.

To this day, Hamilton said, he has not been to the site where his brother died.

"I have no desire to go. It's just too sad," he said. "It's just something I'd rather leave in the past."

A second Titan II missile accident happened on Aug. 24, 1978, in Kansas. Air Force Staff Sgt. Robert Thomas was killed by leaking propellant. Airman 1st Class Erby Hepstall later died from lung injuries related to the spill.

A third Titan II missile accident happened on Sept. 19, 1980, in Damascus in Van Buren County. A tool rolled off a platform and punctured the missile's fuel tank. An explosion a few hours later killed Senior Airman David Livingston.

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan ordered that all of the nation's Titan II missile sites be deactivated. The massive weapons were pulled from their individual silos and transferred to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona and the former Norton Air Force Base in California.

The last Titan II missile in the nation was deactivated on May 5, 1987. It was housed in Silo 373-8 near Judsonia.

All but one of the missiles were broken up for salvage in 2006. A single Titan II is on display at the Titan Missile Museum at Sahuarita, Ariz.

Lay, who has spoken publicly on numerous occasions about his experiences, is the founder and owner of a Little Rock advertising agency, the father to three and grandfather to four.

He has never been back to the site of the accident.

"I didn't so much have guilt that I survived and others didn't, but I have always wondered, 'Why me?' Fifty-three guys got up that morning and kissed their wives and kids goodbye," Lay said. "When the families look at me and say, 'Gary Lay got out, but my brother didn't, my dad didn't,' I think it's important that they know that I tried to do the right thing.

"I've always had a sense that maybe there was something I was supposed to do, and that's why I survived. I've tried to help people every way that I can. I've been a good husband, a good friend. I live life to the fullest."

SundayMonday on 08/09/2015