NAPLES, Italy -- The United States is considering establishing a new network of military bases in Iraq to aid in the fight against the Islamic State, senior military and administration officials said Thursday, potentially deepening American involvement in the country after setbacks for Iraqi forces on the battlefield.

Speaking to reporters aboard his plane during a trip to Italy, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of staff, Gen. Martin Dempsey, described a possible future campaign entailing the establishment of what he called "lily pads" -- U.S. military bases around the country from which trainers would work with Iraqi security forces and tribesmen in the fight against the Islamic State.

Dempsey's framework was confirmed by senior officials in President Barack Obama's administration and comes after an earlier decision this week to send 450 trainers to establish a new military base to help Iraqi forces retake the city of Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province. The general said that base could be the model for a new network of U.S. training bases in other parts of the country.

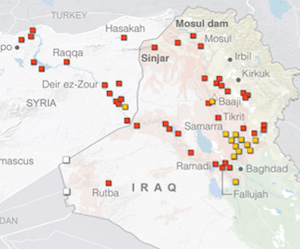

"You could see one in the corridor from Baghdad to Tikrit to Kirkuk to Mosul," Dempsey said. Such sites, he said, could require troops in addition to the 3,550 that the president has authorized so far in the latest Iraq campaign, although he said later that some of the troops at the new bases could come from forces already in Iraq.

For Obama, who spent much of his first term orchestrating the total withdrawal of U.S. combat troops from Iraq and for the past year has publicly resisted making major troop commitments there, establishing new U.S. bases within Iraq would be another step toward deeper entanglement in the country.

Further, the creation of persistent, American-staffed bases in the Iraqi countryside would give the Islamic State obvious new targets, allowing it to expand its fight directly against U.S. forces -- a possibility the group's propaganda operation has publicly reveled in.

Military officials acknowledge that the more U.S. troops there are on the ground in Iraq, the greater the incentive for Islamic State militants to attack them.

There is already precedent: In February, eight suicide bombers who Defense Department officials said were with the Islamic State managed to get into an air base west of Baghdad where hundreds of U.S. Marines were training Iraqi counterparts. Although officials said the bombers were killed almost immediately by Iraqi forces, the assault was a reminder that even circumscribed training missions create a risk for American casualties.

One Obama administration official, who would discuss the issue only on the condition of anonymity, called Dempsey's description "entirely consistent" with the president's strategy in Iraq but noted that Iraqi officials would have to sign off.

"If there is a request from the Iraqi government and the president's military advisers recommend additional venues to further the train, advice and assist mission, the president would certainly consider that," the official said.

The model for a potential new network of U.S. bases in Iraq is already being built at al-Taqqadum, an Iraqi base near the town of Habbaniya in eastern Anbar. The U.S. troops being sent are to set up the hub primarily to advise and assist Iraqi forces and to engage and reach out to Sunni tribes in Anbar, officials said. One focus for the Americans will be to try to accelerate the integration of Sunni fighters into the Iraqi army, which is dominated by Shiites.

Dempsey said he has not recommended putting U.S. troops closer to the battlefield to call in airstrikes -- a step that critics of the current U.S. approach say is overdue, even though it raises the risk of American casualties. But he pointedly held out the possibility that it may become necessary.

"We continue to plan for and ensure that that option is available should it be necessary to have to ensure Iraqi success," he said, adding, "We may reach that point."

Asked why he has not yet recommended it, Dempsey said he believes it could backfire if not done for the right reasons.

"For discreet, limited offensive operations where Iraq security forces have the momentum, I think there is a possibility we'll do that at some point," he said. "But as I've said, I just don't think we're there yet."

Dempsey said the use of American troops to call in airstrikes could even happen in the push to retake Ramadi, a city lost last month by Iraqi forces who had not received U.S. training, or in a counteroffensive to oust the Islamic State from other key cities like Mosul or Beiji. But to use U.S. troops in that role on a regular basis would discourage the Iraqis "from really getting serious about restoring their own security," he said.

While retaking Ramadi is the goal of the training hub at al-Taqqadum, Dempsey indicated that that effort may be months away. While declining to put a timetable on when the battle to retake Ramadi will begin, he said it would take several weeks for the initial command and control center at al-Taqqadum to be set up.

"Timetables are fragile," Dempsey said. "They are dependent on so many different factors."

For the Pentagon, the timetable issue has been a tense one, as the U.S. Central Command and the Iraqi government have clashed in the past about the pace of efforts by the Iraqi security forces to retake areas captured by the Islamic State, also known by the acronyms ISIS or ISIL.

An official from Central Command told reporters in February that an assault to capture Mosul, which fell to the Islamic State a year ago, was planned for this spring. But some Iraqi officials bristled at that, and plans to mount an offensive on the city have been delayed indefinitely. The fall of Ramadi, about 70 miles from Baghdad, put that city higher on the priority list.

Obama has been loath to commit a large number of U.S. ground troops to Iraq. Administration officials say that it is up to the Iraqi government to lead the way in reclaiming its territory and cities from the extremists and that the Shiite-dominated government can do so only by being more inclusive toward the country's Sunni minority.

Dempsey said the United States was still hoping the Iraqi government would find a way to engage Sunnis to beat back the Islamic State, but he also talked of what he called a "Plan B" in case that never happens.

"We have not given up on the possibility that the Iraqi government could absolutely be whole," he said but added that "the game changers are going to have to come from the Iraqi government itself."

"If we reach a point where we don't think those game changers are successful, then we will have to look for other avenues to maintain pressure on ISIL, and we will have to look at other partners," he said.

Dempsey said that he did not envision another military base in Anbar but that Pentagon planners were already looking at more-northern areas for additional sites.

The Obama administration is hoping that reaching out to Sunnis will reduce the Iraqi military's reliance on Shiite militias to take back territory lost to the Islamic State.

To that end, the Americans will be sending arms and equipment -- including AK-47s and communications equipment -- directly to al-Taqqadum. The supplies are to be transferred to Iraqi army units that are then supposed to give them to Sunni fighters. U.S. military officials said U.S. soldiers would be there to ensure the transfer to Sunni fighters.

Officials said the Iraqi security forces were expected to do the bulk of the work to retake Ramadi once that campaign gets going. But once the city is reclaimed, it will probably be the Sunni fighters who will have to hold it.

"What the tribes are going to provide is not only thickening of the ranks of those fighting ISIL, but at some point the [Iraqi security forces] will want to protect" the cities that have been liberated, Dempsey said. "The responsibility of defending the cities that are liberated -- that will fall to the local tribes."

The Pentagon said Thursday that the U.S. has spent more than $2.7 billion on the war against Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria since a U.S.-led coalition began airstrikes in August, and the average daily cost is now more than $9 million.

Although the U.S. has no troops on the ground, the fight against the Islamic State has attracted dozens of Westerners, including Iraq War veterans who have made their way back to the Middle East to join Kurdish fighters, who have been most successful against the extremist group.

The body of an American who died fighting with Kurdish forces in Syria against the Islamic State was handed over on Thursday to his family at a Turkish border crossing, a Kurdish official said.

Hundreds of people turned up in the Kurdish town of Kobani to bid farewell to Keith Broomfield before his body was handed over to family at the Mursitpinar gate, said the official, Idriss Naasan.

Broomfield, from Massachusetts, died June 3 in battle in a Syrian village near Kobani, making him likely the first U.S. citizen to die fighting alongside Kurds against the Islamic State.

Family members spoke to the media on Thursday outside their manufacturing business in Bolton, 30 miles west of Boston. They said they hope his body will be brought back to the U.S. on Saturday.

His father, Tom Broomfield, said Keith Broomfield went to Syria with no contacts and knew it was "a crazy thing to do" but felt strongly that he needed to help in some way.

"He just felt he should be going," Tom Broomfield said.

Information for this article was contributed by Helene Cooper and Michael Gordon of The New York Times; and by Robert Burns, Lolita C. Baldor, Zeina Karam and Denise Lavoie of The Associated Press.

A Section on 06/12/2015