Arkansas has a rich and complicated history. And the richly complicated people who made that history left behind artifacts that describe their lives. Some of those artifacts are lost forever. Others survive and are accessible to the public.

Several Arkansans -- preservationists, historians, archaeologists -- were asked what they consider to be the best artifacts. They responded, graciously, and cumulatively created a list long enough to write a book.

Ten of those are described here.

But first, a definition of "artifact" from Ann M. Early of Fayetteville, the state archaeologist: "Physical objects that have been modified, or fashioned, by mankind as opposed to objects that have been fashioned by nature."

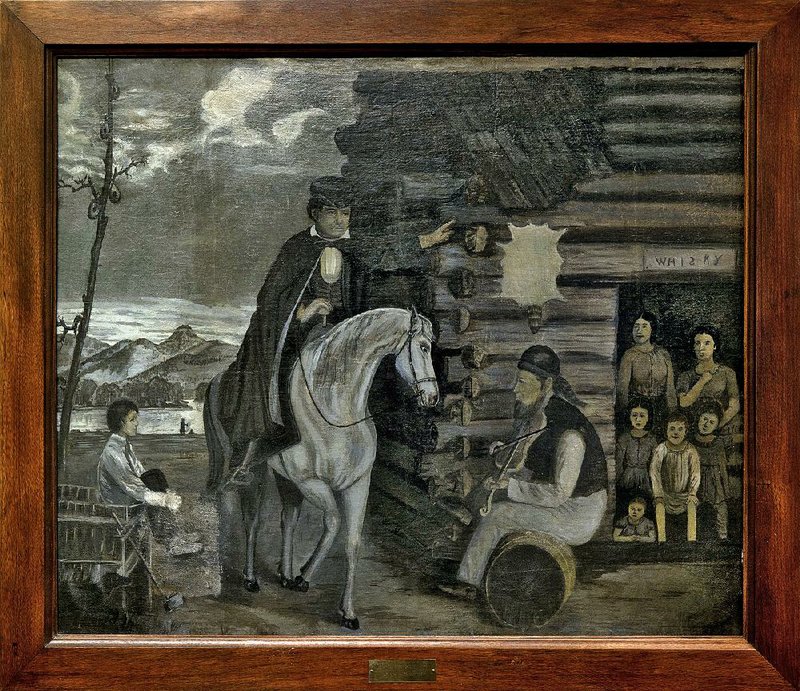

WHAT: The original painting of The Arkansas Traveler by Edward Payson Washbourne

WHERE: Arkansas History Commission, behind the state Capitol, Little Rock

WHY: Washbourne's painting dates to 1856. It is based on the tale of Col. Sanford Faulkner, who was lost in rural Arkansas in 1840 and stopped at a squatter's cabin to ask for directions. Faulkner wound up playing the second part, or "turn," of the tune being played by the squatter on a fiddle.

A tune called "The Arkansas Traveler" also emerged about that time. When the sheet music was published, it was titled "The Arkansas Traveller and Rackinsac Waltz." A 1922 version was one of the first 50 recordings in the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry.

Washbourne's painting was popularized by a lithograph in 1859, and included the sheet music.

The image created by the painting -- Arkansas and its hillbillies -- has persisted. As has the Arkansas Traveler nickname. Visitors are honored by Arkansas Traveler certificates, and the Little Rock Travelers baseball team began play in 1901, later becoming the Arkansas Travelers.

The original painting at the History Commission is accompanied by Washbourne's self-portrait and a lithograph with the sheet music. He died in 1860 at 29.

Julienne Crawford, History Commission curator, is confident the painting is the original. It was donated to the commission in 1957 by descendants of Washbourne's sister, Abigail Washburn Langford, along with the self-portrait and two other paintings.

WHAT: 1824 Quapaw Treaty

WHERE: Arkansas History Commission

WHY: The treaty took away all land owned by the Quapaw Nation. The tribe lived in what became Arkansas and first encountered French explorers about 1673. Epidemics and depredations by other tribes reduced the Quapaw to no more than 750 by the time of the 1824 treaty.

In 1818, the tribe gave up 30 million acres in exchange for a million acres between the Arkansas and Ouachita rivers. Land along the Arkansas River was sought by settlers, and in the 1824 treaty the tribe gave up the rest of its claim. Land was given to the Quapaw along the Red River in Louisiana.

Fifteen members of the Quapaw tribe signed the treaty. Each wrote an X after his name. Representing the United States, and signing the treaty, was Robert Crittenden, later a governor of Arkansas.

In addition to the land in Louisiana, the Quapaw were given $4,000 in goods and an annuity of $2,000 a year for 11 years.

The tribe wound up in northeastern Oklahoma. It's back in Arkansas by virtue of its ownership of 160 acres near the Little Rock industrial port.

Crawford said the treaty is available for viewing only by approval of the director, Lisa Speer. Digital copies are available.

Credit for its existence goes to John L. Ferguson (1926-2006), the state's longest serving historian, said Richard Davies, executive director of the Department of Parks and Tourism.

"He came into my office and said, 'Look what I found,'" Davies said of a day in the late 1970s or early 1980s. "They were throwing stuff away in the basement of the state Capitol. He went through the boxes and salvaged it."

WHAT: Toltec Mounds

WHERE: Lonoke County

WHY: Two large mounds -- 49 feet high and 39 feet high -- plus several smaller mounds were built between 650 and 1050 by American Indians of the Plum Bayou culture. The site is now a state park, established in 1980. "That makes it outstanding in its own right," Elizabeth Horton, the archaeologist there, said.

"It speaks to the long, deep human history in Arkansas. It also speaks to Arkansas' willingness to protect and preserve the past."

Horton sometimes speaks to students about Toltec.

"I oftentimes talk about what it says about how phenomenal the engineering skills of these people were, these native American Indians. These were incredible features of landscape engineering."

Toltec "is a glimpse of, a chance to see, large-scale human ingenuity, pre-modern, on the landscape. And to see just how sophisticated the people were who were before us."

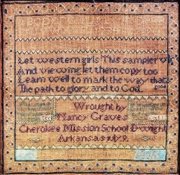

WHAT: the Graves sampler

WHERE: Historic Arkansas Museum, 200 E. Third St., Little Rock

WHY: Nancy Graves, a Cherokee, made this sampler at age 11 in 1828 at a Presbyterian school, Dwight Mission, near what is now Russellville.

The school educated and Christianized Cherokees on their way west from Tennessee and Georgia.

"A sampler was a way for every well-brought-up lady of European descent to show her ability as a productive member of society," Bill Worthen, director of the museum, said. And so it was for Cherokees, he said, "in a place as rough and unsettled as anywhere in the organized territory of the United States."

Nancy's Cherokee name was Ku-To-Yi. Part of the sampler reads: Let western girls This sampler view/And viewing let them copy too/Learn well to mark the way that's good/The path to glory and to God.

The sampler is on display at the museum, and should be for a while, Worthen said.

Worthen said the museum acquired the sampler in 2013 at an auction at Sotheby's in New York, bidding against the Smithsonian Institution. The purchase was possible by a grant of more than $80,000.

"It's a window on so many aspects of our history," Worthen said. "The Native American experience in Arkansas, the religious experience in Arkansas, the way of life on the frontier."

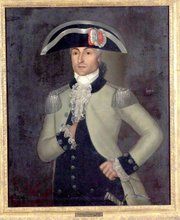

WHAT: portrait of Don Joseph Bernard Valliere d'Hauterive

WHERE: Historic Arkansas Museum

WHY: Valliere, a Frenchman, was Spanish commandant of Arkansas Post, and previously served the French crown in Arkansas. In 1793, Spain awarded him a grant of more than 6 million acres, a mass of land, the museum said, equal in size to Belgium.

The artist, Jose Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza, was the pre-eminent portraitist of colonial Louisiana. The portrait was likely done in New Orleans about 1787.

Arkansas Post was the first, and most important, European settlement in Arkansas, dating to 1682 when the French officer Henri de Tonti acquired land and a trading concession at the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers.

Valliere, Worthen said, "represented the European presence before this became the United States. It was a period when all things seemed possible."

Valliere hangs in the Historic Arkansas Museum, a gift in 1994 of Mr. and Mrs. A. Howard Stebbins III.

WHAT: the Baring Cross Bridge

WHERE: over the Arkansas River, downtown Little Rock

WHY: On its site was the first permanent bridge over the Arkansas River, Cary Bradburn, city historian of North Little Rock, said. Until the bridge's construction in 1873, the only way across was by ferry -- except, he said, when the river was low enough to walk. A deck was built on top of the bridge in 1877, so the bridge doubled as a highway bridge for the public.

"It was a link to the railroad system, which was an economic engine," Bryan McDade, curator of collections at the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in Little Rock, said.

The bridge allowed for more efficient use of the railroad, McDade said -- no waiting for ferries. And it was operable even when the river was too high for ferries.

That bridge was swept away by the great flood of 1927. Rebuilt and reopened in 1929, the bridge was later modified with a lift span to accommodate river traffic.

About 25 Union Pacific trains pass over the bridge every day.

"It's a critical piece of the Union Pacific infrastructure," railroad spokesman Jeff DeGraff said, and the last remaining active railroad bridge in the Little Rock-North Little Rock area.

WHAT: Portrait of John Drennan by George Catlin

WHERE: Historic Arkansas Museum

WHY: Drennan (1801-1855) was a businessman and Indian agent in Van Buren. Catlin was a painter whose specialty was portraits of American Indians.

Is the Drennan portrait noteworthy for Drennan or Catlin?

"Absolutely both," Worthen said.

"When Catlin came out West to document the Indians, at one point he stayed with Drennan and painted a number of Indians at the Drennan house. Catlin was a very important figure. Without him our understanding of the Indian world would be greatly diminished."

As for Drennan, "he was a major player in early Arkansas, a very important businessman in Van Buren, agent to the Choctaws, and a regional superintendent for the Bureau of Indian Affairs."

Historic Arkansas Museum has the painting in storage, but has displayed it. It was acquired after the death of the last person of the last generation to live in the Drennan-Scott House in Van Buren, Worthen said.

The original one-room house was built between 1834 and 1836. The expanded house is a museum operated by the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith.

WHAT: a woven fiber bag filled with chenopodium (aka goosefoot) seeds

WHERE: University of Arkansas Museum, Fayetteville

WHY: The brown bag, made of dried grasses, was found in 1932 in a rock shelter at Eden's Bluff in Benton County, Mary Suter, curator of collections, said. It's about 10 inches tall and 6 inches around, with a cord tie at the top. When found, it was filled with "teeny-tiny brown-black seeds." She described the bag as "beautifully preserved."

Eden's Bluff is now under Beaver Lake, Suter said.

State Archaeologist Ann M. Early said the bag is about 2,000 years old and represents the participation of ancient Arkansans in the domestication of plants and animals.

Early said there are a handful of places in the world where people independently domesticated plants and animals, which led to more complex societies. One of those places is the United States' southeast. The bag and its seeds show that Ozark residents were among those pioneers.

The bag was recently returned to the museum from Louisiana State University, where it spent 10 years with researchers there.

"It's available to other researchers," Suter said. "We're not likely to put it on exhibit because we don't have an exhibit venue."

WHAT: Louis Jordan's saxophone

WHERE: The Old State House Museum, 300 W. Markham St., Little Rock

WHY: "You can draw a line of American popular music from vaudeville to hip-hop and he is the common thread to all of those genres of music," said Stephen Koch, author of Louis Jordan: Son of Arkansas, Father of R&B. His syndicated radio program Arkansongs is broadcast on Arkansas affiliates of National Public Radio.

Jordan was born in Brinkley in 1908 and died in Los Angeles in 1975.

"He was an incredibly popular artist of the 1940s," Koch said. "He sold millions of records and had more than 50 Top 10 hits. Another reason we consider him an innovator was that he permeated the culture with phrases like 'Ain't nobody here but us chickens.' We still say that today."

The saxophone, Koch said, "is a fantastic talisman for everything that came out of American music."

Bill Gatewood, museum director, said the saxophone was acquired in 2002. It was bought from a collector of music memorabilia. It's currently on exhibit.

"Jordan influenced everyone we consider influencers today," Koch said. "Ray Charles, James Brown, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Bill Haley, Sonny Rollins -- they all say their inspiration was Jordan."

WHAT: A granite monument at Louisiana Purchase State Park

WHERE: on Arkansas 362 at the juncture of Lee, Monroe and Phillips counties

WHY: France sold 828,000 square miles of its Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803. Twelve years later, President James Madison ordered a survey of the area, which stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border.

The survey's initial point was at this spot, and began in October 1815. Two surveyors, Prospect Robbins and Joseph Brown, spent months on the project using only a compass and a chain.

John Gill, a Little Rock lawyer and member of the state Parks, Recreation and Travel Commission, said the survey opened the West.

"It was the vehicle which made it possible for people to own land in a legal manner," he said. "Up to that point land was measured from a creek to the next barn."

The monument was placed in 1926 by the L'Anguille Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The park was established in 1961.

An elevated boardwalk above the headwater swamp of the Little Cypress Creek watershed leads to the monument.

"It's an absolutely magical area," Gill said. "You're out there in the middle of nowhere, walking on water."

Style on 06/21/2015