It’s hard to imagine how Morrilton would function without Raymond Chambers.

The retired, 75-year-old South Conway County School District superintendent played a role in the desegregation of the district and is a member of about a dozen organizations.

Leann Haynes of Morrilton, who serves on the Conway County Care Center Board, of which Chambers is chairman, is one of his bigger fans.

“He’s so awesome. He’s a retiree and works so hard in this whole community, he and his wife,” Haynes said. “Raymond’s in about everything going on in this community. Since he retired, he’s filled up every bit of his time giving back. I think the world of him, and I just appreciate him. … No one wanted to take over this care center [board], and he’s taken it for several years and just done a world of good.”

Others in the community have taken notice of the good he’s done, too. Chambers said the 2015 Prestigious Human Rights Award that the Conway County Church Women United and the Martin Luther King Jr. Committee presented to him is “one of the things I’m real proud of.”

He said his accomplishments come not from being the smartest, but from being determined.

Chambers grew up in Hot Springs, where his father worked for Southwestern Bell and his mother worked at the Lamar Bathhouse.

“That was when Bathhouse Row was going strong,” Chambers said. “I didn’t know many people in Hot Springs who didn’t have a job. I bell-hopped and waited tables, summers and at night. Hot Springs was wide open. I made some pretty good tips,” he said.

Chambers said he attended the segregated Langston High School, although he said that at that time, not many minorities lived in the city. There were 34 students in his class, but he said courses such as chemistry and biology were rigorous.

“We had some top-notch teachers — very good teachers,” he said. “They expected a lot out of you.”

He said he was never on the honor roll, but he worked hard.

“Growing up, I was not the smartest kid in the class, but I was determined, I guess, that I was going to make it,” he said.

After graduation, he went to Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri, for a year, then went with friends to Texas Southern University in Houston, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology. He later earned master’s and specialist degrees in administration from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, as well as a master’s degree in social studies from Henderson State University in Arkadelphia.

Chambers said a professor at Texas Southern told students, “If you want to go somewhere, you have to learn how to write, how to express yourself,” and Chambers gave his students the same advice.

“I said [segregation] is not going to last forever, and it’s going to be more competitive. I didn’t see but one way out for me, and that was education,” he said.

He moved back to Hot Springs from Texas. “I love Arkansas,” he said. He earned his degree from Henderson while teaching social studies and economics from 1963 to 1972 at the segregated Arkadelphia High School that became desegregated while he was there.

“We had a little riot there. I looked up one day, and African-Americans and whites were battling each other, and I was out there trying to stop it by myself. I got them headed off to campus. About that time, here come some coaches,” he said. “It was a minor riot; it wasn’t where anybody got hurt.”

Police were brought into the school after that, he said.

After a brief stint as a venture analyst at the West Central Arkansas Planning and Development District in Hot Springs, which serves 10 counties, Chambers became an advisory specialist for a program supervised by Ouachita Baptist University in Arkadelphia. He consulted on various education issues, including assessment and curriculum development, and assisted school districts that were “having problems with desegregation,” he said. “We would go in and try to help them out with their problems.” He also conducted workshops — mostly in the southern part of the state — on strategies related to race relations and gender.

The key was for the community and school to work together, he said.

He also, under the direction of the federal government, helped draft a plan for desegregation of Conway County schools.

Chambers said he was working in De Queen, Arkansas, with an adult-ed program at a community college and attending UALR to get an administrative degree.

A friend of his from the Arkansas Department of Education called and asked Chambers if he would be interested in being a superintendent at a school “and help with desegregation.” When Chambers found out it was Menifee in Conway County, he agreed, because he had heard good things about the school.

That was in 1976, and school districts in the county were in federal court fighting to remain segregated. However, the school districts in Morrilton, Plumerville and Menifee were ordered consolidated into the South Conway County School District in 1979 and 1980. Chambers, in 1980, became assistant superintendent over personnel and curriculum for the district, a position he remained in for 18 years.

“I moved [to Morrilton] in 1980, the hottest summer ever,” he said. “This community was one of the best I had worked with on desegregation. That’s the reason I stayed here.”

Chambers said he decided that “everyone would be bused. Regardless of who you were, you were going to be bused.”

He said he urged his former Menifee students to “participate in everything” at their new school.

“We had fewer problems during the four years I worked with the federal program than other school districts,” he said. “I said, ‘This is a good place to raise my children.’ I didn’t have to worry about any of my children walking the streets being safe at night.”

When then-Superintendent Ray Fullerton retired in 1998, Chambers was hired to replace him. When someone asked Chambers why he didn’t do more to recruit minorities to teach, “I said, “I tried.’ We couldn’t pay what Conway paid.”

However, Chambers said he was able to build a strong working relationship with the people in the county.”

“Someone said, ‘I don’t like you because you’re African-American, but I respect you.’” He recalled that the mother of a white student stopped him in public to tell him how much she appreciated what he’d done for her child to persuade her to stay in school.

Chambers retired as superintendent in 2003, just because he thought “it was time.”

“[The school board] didn’t want to accept my resignation at first, and I said, ‘Oh, yes,’” he said, laughing.

Chambers was well-known in education circles, and shortly after he retired, he was asked to be on an Arkansas Department of Education committee to review standardized tests. The committee’s responsibility was to identify potential bias or sensitivities, and he traveled to Minnesota and Pennsylvania three or four times a year from 2005 to 2012.

“We would spend three to four days at work; we would turn in our work and leave. They would bring people in … to look at the questions to decide if they were fair, they were biased or whether they were sensitive, and whether they needed to stay in the test,” he said.

“Sometimes we forget in America that when we opened our doors, we not only brought the people in; we brought their culture in,” he said.

A company representative called Chambers this year and asked for his help again with the tests, and this time he read the tests online.

One of his first volunteer efforts in Conway County was through the Area Agency on Aging, he said, where he was on the board for six years. He now serves as assistant chairman of the organization’s foundation board.

Chambers sat at a table at the Workforce Center in Morrilton, one of the places he volunteers.

He is secretary-treasurer of the West Central Arkansas Workforce Development Board, which awards the grant to the Workforce Center in Morrilton to run its program. The center has programs to help people get jobs — youth ages 16-24 who are out of school, dislocated workers and adults.

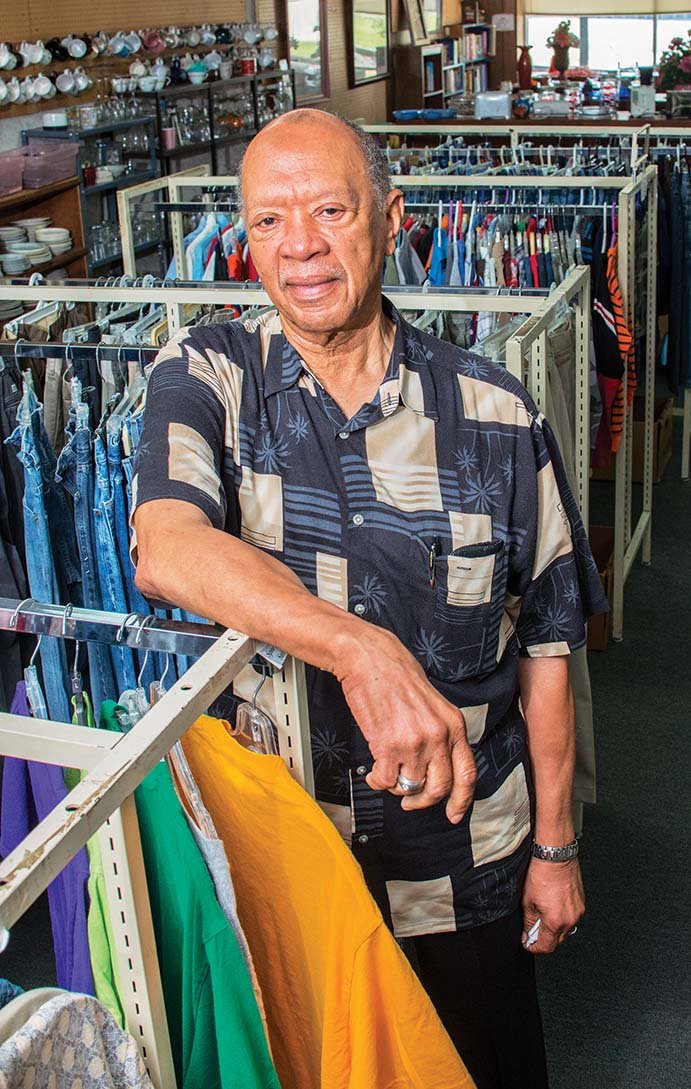

Another organization that is near and dear to his heart is the Conway County Care Center & Thrift Store.

“I never really knew till I got involved with the Care Center how hungry Arkansas is, and they need help with utilities and other things,” he said.

Chambers started several years ago by running the cash register at the thrift store and, “the next thing I knew, I was on the board,” he said. He’s been chairman since 2011. The center’s major food drive, Harvest of Hope, is underway and will culminate Oct. 24 with a Fill the Truck event in the parking lot of Ace Hardware and Kroger in Morrilton.

He’s also passionate about the South Conway County School Foundation, which will have its Race to the Future fundraiser/dinner at 6:30 p.m. Tuesday at Morrilton High School.

“Our main objective is to help schools here acquire the necessary equipment they need for students to be able to prepare for the future. Technology is here,” he said. “These businesses now, they want these kids with these skills.”

Chambers said his biggest concern is “who is getting left behind.” That’s why he works with a youth group at Workforce.

“I am a little concerned about the life some of them are leading,” he said.

Family First is a passion of his — it is a school program started under Gov. Bill Clinton’s administration in which a collaborative effort is used to assist at-risk youth. When Chambers retired as superintendent, “the lady who had been operating [Family First] went in as a regular teacher. Instead of letting it die as it had in other schools in Arkansas, I took it over,” he said.

Chambers is trying to rebuild Family First because the paperwork wasn’t filed on time with the federal government, and the organization lost its nonprofit status. Family First’s board has been somewhat inactive, but he said the group is important.

“Its purpose is to provide assistance to the community,” he said, especially low-income families and children.

Of course, he is leading the charge. He’s met with the school district’s superintendent, law enforcement personnel, the county judge and the chancellor of the University of Arkansas Community College at Morrilton — as if Chambers didn’t have enough to do.

“I haven’t learned to say no yet,” he said.

Lucky for Morrilton.

Senior writer Tammy Keith can be reached at (501) 327-0370 or tkeith@arkansasonline.com.