Last in a series

A national study of ethics rules, campaign donations and state judges gave Arkansas a grade of "F."

The state had a lot of company: 31 of 39 states that hold judicial elections got failing grades, according to the report by the Center for American Progress.

The center ranked states on how well they have modernized judicial ethics and campaign finance-reporting rules to address a growing influx of cash into court elections.

Some experts urge scrapping judicial elections and appointing judges through a merit-selection system.

Others propose changing ethics rules for elected judges to require them to disclose campaign contributions in every case that goes before them, or to disqualify themselves from cases in which lawyers gave donations that topped set limits.

Big donors "want judges who are going to rule a certain way. Not just in their cases -- they want a certain judicial philosophy. It's really alarming," said Billy Corriher, an author of the Center for American Progress' 2014 study.

Most experts believe "there's no other practical reason" to give large campaign contributions in judicial races, he said. The Washington, D.C., think tank says it works to improve Americans' lives "through bold progressive ideas" and describes itself as nonpartisan.

The American Bar Association, Washington, D.C.-based Justice at Stake, the Center for American Progress and the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University all study ways states can help prevent improper influence, or the appearance of improper influence, in their courts.

The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported Sunday that six law firms that work together on class-action civil cases in Arkansas are, as a group, among the biggest campaign donors to the six elected members of the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Keil & Goodson of Texarkana and five firms from Texas, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania have contributed an estimated $296,000 to the campaigns of Justices Courtney Goodson, Karen Baker, Robin Wynne, Paul Danielson, Josephine Hart and Rhonda Wood, the newspaper's review of campaign contributions found.

The other law firms are Nix Patterson & Roach of Daingerfield, Texas; Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check of suburban Philadelphia; Crowley Norman of Houston, Texas; attorneys Reggie Whitten and Michael Burrage of Oklahoma, affiliated with several firms over the past dozen years; and attorney Jason Roselius of Oklahoma, also with multiple law firms, according to case records.

Representatives of the law firms did not respond to requests for interviews.

Arkansas Supreme Court justices have heard cases involving the law firms and decided in their favor, the newspaper found. The decisions often led to settlements that included millions of dollars in legal fees for those law firms.

Arkansas also has court rules and procedures that are among the friendliest in the nation for class-action lawsuits, according to law professors. Those rules help class-action plaintiffs and their lawyers win, critics say.

The Arkansas Supreme Court adopts and sets those rules of civil procedure.

Courtney Goodson, who is running for chief justice this year, is married to John Goodson of the Keil & Goodson law firm.

Her 2010 high court campaign reported $142,500 in contributions from the six law firms, the most of any elected justice. She didn't respond to specific questions from the newspaper regarding campaign contributions and potential conflicts of interest, except to say she follows the state's ethics guidelines.

Other Arkansas Supreme Court justices past and present who did respond to interview requests said they purposely try not to learn who their donors are, as the state Code of Judicial Conduct instructs.

Here's how Arkansas compares on key issues proposed by national groups to keep bias out of the courts:

• Does the state set a dollar or percentage limit on a donor's campaign contribution that would require a judge to recuse in cases involving the donor?

Not Arkansas.

The American Bar Association's model code of judicial conduct, which most states use as a guide for their rules, has recommended such limits since 2008.

Only a handful of states have set a definite amount, from as low as $50 to a high threshold of $5,000.

"It's better to have a hard rule," said the Center for American Progress' Corriher. "That goes a long way toward assuring the public that judges aren't biased."

The Center for American Progress (americanprogress.org) was founded in 2003 as a liberal alternative to more conservative think tanks. Its first president and CEO was John Podesta, former chief of staff to President Bill Clinton. Tom Daschle, former Democratic U.S. senator from South Dakota, is the current president and chief executive.

• Are campaign contributions listed as a basis for a judge to recuse from a case?

Arkansas got a score of minus-5 on this question from the Center for American Progress. That's because the Arkansas Code of Judicial Conduct essentially says the opposite: a campaign contribution "does not of itself disqualify the judge."

The state code does go on to say: "However, the size of contributions, the degree of involvement in the campaign, the timing of the campaign and ... other factors known to the judge may raise questions as to the judge's impartiality."

• Must a judge recuse whenever his "impartiality might reasonably be questioned?"

Arkansas' code contains this provision. But it also advises judges to avoid knowing who contributed to them, putting the two provisions at odds, experts say.

• Is the judge required to disclose on the record any campaign contributions from parties in a case?

Not according to the Arkansas code.

It does contain a more general statement that a judge "should disclose on the record information that the judge believes the parties or their lawyers might reasonably consider relevant to a possible motion for disqualification."

The newspaper's search of court records involving the class-action donor firms did not reveal any disclosures of Supreme Court justices' campaign contributions.

• Does a state's Code of Judicial Conduct suggest -- as Arkansas' does -- that judges try "as much as possible" to remain ignorant of their contributors and their contributions?

The American Bar Association model code does not contain such a provision. The judicial codes of a handful of states do.

"In some states, those rules have been criticized as providing a screen," said Alicia Bannon, senior counsel with the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

"Because public confidence is such an important factor in when judges should be stepping aside, there is reasonable skepticism about how insulated judges really are from their donors," she said.

The 20-year-old Brennan Center for Justice was founded by the family and former law clerks of U.S. Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan. The center (brennancenter.org) describes itself as part think tank, part advocacy group, part public interest law firm. It works on issues that include voting rights, minimum wage, campaign finance law and national security.

• Does the state require parties in a case, including attorneys, to disclose campaign contributions made to the judge or judges?

Arkansas doesn't, along with many other states. New York is one that does. Court administrators there, not judges, review the information and decide which judge should preside -- or not.

• Does the state appoint or elect its judges?

Justice At Stake, a nonpartisan advocacy and education group, has a goal of convincing more states to appoint rather than elect judges.

"Data shows special interests are investing very, very heavily to give meaning to the old joke: 'So-and-so is the best judge money can buy,'" said Mark Harrison, board chairman of the Washington, D.C.-based coalition of about 50 groups, ranging from bar associations to the League of Women Voters and various good-government groups.

"The worst part of all this: there are a great many judges very uncomfortable having to rely on campaign contributions from litigants who will appear in front of them," Harrison said. "But the only way they can stay on the bench is to accept them."

Founded in 2000, Justice at Stake (justiceatstake.org) also advocates for tighter campaign finance laws for state-level judicial races. Its mission statement proclaims it is the "only national organization that focuses exclusively on keeping courts fair and impartial."

Arkansans have debated for years whether to elect or appoint judges.

Last April, after turmoil among Arkansas Supreme Court justices involving handling of a gay marriage appeal was made public, Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson and former Democratic Attorney General Dustin McDaniel said they wanted to take another look at appointing Arkansas' appeals court judges.

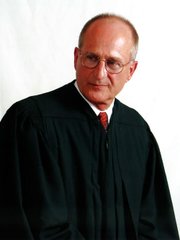

Retired state Supreme Court Justice Robert Brown says he realizes the difficulties in electing judges: "Other politicians are supposed to listen to their constituents. Justices are supposed to listen to the law. They are supposed to be objective, disinterested, yet they have to be elected."

When debates have surfaced over the issue, "I was among those who went with elected," Brown said. "I didn't think the people of Arkansas would give up their right to elect judges."

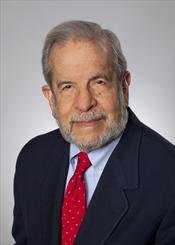

David Stewart, retired director of the state Judicial Discipline and Disability Commission and a former judge, takes the opposite side: "In my opinion, we ought to switch to an appointed process.

"You eliminate the prospect of people perceiving that judges are going to act like an ordinary politician and decide cases based on who has the most money."

• Is independent or "dark money" spent on a campaign listed as a basis for a judge to disqualify from a case?

The Arkansas Code of Judicial Ethics doesn't directly address this kind of spending.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United ruling tossed out limits on independent campaign spending, millions of dollars in "dark money" from unidentified donors have injected attack advertising into state judicial races.

Judicial experts question how the public can know if a judge has a conflict of interest if the donors behind the attack ads that helped elect them are unknown.

In 2014, the first "dark money" from unknown contributors -- which national experts estimated at $165,000 -- flowed into an Arkansas Supreme Court race. That money paid for last-minute negative ads to help then-C̶i̶r̶c̶u̶i̶t̶ ̶J̶u̶d̶g̶e̶ appeals court Judge* Robin Wynne defeat Little Rock attorney Tim Cullen. Wynne won 52 percent to 48 percent.

In the fall of 2015, campaign contributions for state judicial races nationwide set a record -- almost $16 million poured into races for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court alone.

CASH AND THE COURT

Six law firms' total contributions to Arkansas Supreme Court races by candidate, 2004-14

Justice Courtney Goodson: $142,500 | [DETAILS]

Court of Appeals Judge Raymond Abramson: $82,050 | [DETAILS]

Justice Karen Baker: $66,000 | [DETAILS]

Former Justice Jim Gunter: $27,619 | [DETAILS]

Circuit Judge Tim Fox: $26,000 | [DETAILS]

Justice Robin Wynne: $25,000 | [DETAILS]

Justice Paul Danielson: $23,500 | [DETAILS]

Justice Josephine Hart: $22,000 | [DETAILS]

Former Chief Justice Jim Hannah: $17,250 | [DETAILS]

Justice Rhonda Wood: $17,000 | [DETAILS]

Former Justice Donald Corbin: $3,000 | [DETAILS]

- MAIN MENU

- PART I: 6 law firms top donations list

- PART II: Top donors net big wins

- PART III: Campaign money stirs debate over how judges picked

- State justices respond to donation questions

- After 2010 high court race, justice wed a top donor

- Firms file suits, donate together

- INTERACTIVE: Breakdown of campaign contributions to justice candidates

- GRAPHIC: Class-action contributions to justices

- How we did it

A Section on 01/26/2016

*CORRECTION: Arkansas Supreme Court Justice Robin Wynne was an appeals court judge when he ran for the high-court seat in 2014. This article misidentified his previous office.